“We die. That may be the meaning of life. But we do language. That may be the measure of our lives.”

—Toni Morrison

I didn’t know Koyo Kouoh.

But I recognized her.

In the way she carried stillness through rooms built to silence us.

In the way she spoke in complete thoughts, even when surrounded by incomplete histories.

In the way she moved—borderless, brilliant, deliberate.

We lose Black women all the time. Quietly. Publicly.

With hashtags. Without funerals.

It doesn’t seem to matter how well they’ve lived, how much they’ve changed, how carefully they’ve built.

The endings still come early.

The headlines still come late.

The grief still arrives long before the world is ready to hold it.

Koyo Kouoh left this earth at fifty-seven.

That number feels like a question no one’s answering.

And I have questions.

About why our sharpest minds burn out in institutions not made for them.

About how brilliance doesn’t immunize us from exhaustion.

About what it means to curate the future and still be undone by the present.

This isn’t just about Koyo.

This is about all of us.

We are still dying young.

We are still leaving behind unfinished sentences.

But this is also a love letter.

A remembering.

A gathering of names, of images, of the work left behind and the beauty that insists on staying.

Because Koyo Kouoh didn’t just curate exhibitions.

She curated a new way of seeing.

And I want to stay there, in that afterlight.

Not just to mourn her.

But to listen.

She Made Room

Koyo Kouoh was a Cameroonian-born, Swiss-raised, Dakar-rooted curator whose work stretched continents. She didn’t enter the art world quietly. She built a new one.

Through RAW Material Company in Senegal and later Zeitz MOCAA in Cape Town, she created spaces where African intellectual and artistic life could breathe—loudly. Where the archive was alive. Where the Western gaze wasn’t the center of the room.

At Zeitz, she didn’t just rearrange exhibitions. She rerouted the institution’s soul.

She didn’t make African art legible to Europe.

She made it sovereign.

She had the kind of curatorial voice that didn’t flinch. She held tension like fabric, folding it into form. Her politics were evident—not only in what she hung on the wall but in why she hung it.

The Language of Looking Back

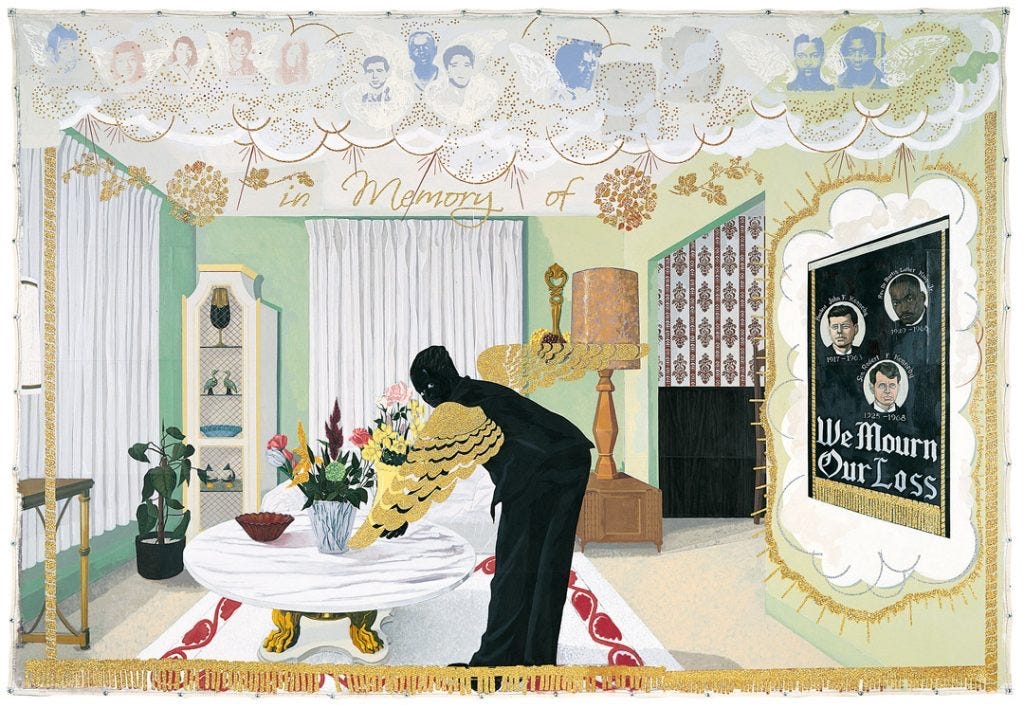

In 2022, she gave us When We See Us, a panoramic exhibition of Black figuration that stretched a century wide. It was more than a show. It was a spell, a syllabus, a sermon.

In the book that accompanied the show, there are portraits that refuse pity.

Bodies that hold both memory and defiance.

Mothers, dancers, ghosts.

A Black boy with a book.

A Black girl looking straight back.

There’s Kerry James Marshall’s Souvenir I, drenched in mourning and insistence.

There’s Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s imagined sitters, painted in solitude but never alone.

There’s Kudzanai-Violet Hwami’s The Healer, where flesh, dream, and spirit collide.

Koyo didn’t ask for translation.

She asked for attention.

She reminded us that representation is not the end of the story.

It’s the beginning of a reckoning.

The Biennale That Won’t Be

In December 2024, Koyo Kouoh was appointed to curate the 61st Venice Biennale, scheduled for 2026.

The Biennale is not a small thing.

It is the global stage of contemporary art—the space where nations build mythologies and curators shape the canon.

It’s where careers are made, where aesthetics are politicized, where the world comes to look and be looked at.

In 129 years, no African woman had ever been appointed to lead it. Until Koyo.

She was in the early stages of planning her vision. She had not yet unveiled the theme—but those who knew her work knew what to expect: emancipation, diaspora, rupture, care, confrontation. She would’ve brought Dakar to the Adriatic. She would’ve made the Western art world see itself through our eyes—for once.

But now, her Biennale will never happen.

The frame is empty. The room is waiting. And the world will only see the outline of what could’ve been.

This isn’t just a personal loss. It’s a structural one.

A moment that was meant to mark a shift in who curates the future—and now, silence.

Why We Keep Losing Our Brightest

I write about grief often in this space, because it keeps happening.

We lose the ones who held us.

The ones who wrote the books, who built the libraries, who whispered us into courage.

The ones who should have been protected. Instead, they were consumed.

Koyo Kouoh was 57. bell hooks was 69.

Toni Morrison was 88, and even that felt too soon.

Too many Black women we love are dying mid-sentence.

The institutions that celebrate them rarely sustain them.

What happens when your name is on the press release but not on the wellness plan? When your labor is honored but your body isn’t?

We should not have to die for the right to be seen.

Curating Against the Frame

Koyo taught us that the frame is never neutral. Curation is not just about taste—it’s about truth. It’s about who gets to be remembered and how. She knew the difference between being shown and being understood.

In one of her final interviews, she said:

We are not curating just for now. We are curating for a tomorrow that has not yet been allowed to arrive.

That line won’t leave me.

She wasn’t just arranging artworks. She was building time machines. She was giving form to the world we haven’t yet had permission to imagine.

A Future We Still Owe Her

We owe her ritual.

We owe her rest.

We owe her refusal.

To every young Black girl wondering if she can enter the art world and matter—Koyo is the answer.

To every curator tired of translating their rage—Koyo is the blueprint.

But we owe her more than admiration. We owe her a world where women like her don’t die from carrying too much. We owe a cultural infrastructure that protects what it praises.

Koyo was building that world. And now we have to finish it.

We Still See Us

If grief is a kind of vision, then Koyo Kouoh sharpened mine.

She showed me that care and critique could live in the same frame. That Black art does not need permission to exist. That curation is a political act, and beauty can be a kind of defense.

Her death gutted me. But her work? Her work still breathes.

In Dakar. In Cape Town. In the books on my desk. In the Black girl writing this. In the person reading it.

We still see us, Koyo. Because you saw us first.

Until next time,

Marley

this is a phenomenal piece of writing

I appreciate you and every word.