BLACK AMERICANA——Stylish and Sublime

Guest post by 6th National Youth Poet Laureate Alyssa Gaines. What The Met theme encourages us to consider about African-Americanness, the South, and the Nation.

Black Americana is an intimate undertaking. It is the smooth shouldering of a double burden, and an exercise of faith. It is a matter of presentation, a performance of citizenship, and an offering to the nation. The Met Gala’s “Superfine: Tailoring Black Style,” as it expanded on Monica L. Miller’s Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity, meditated on transatlantic Black presentation and motioned toward this counter-aesthetic of Americana from the Black transatlantic vantage. With its accompanying exhibition co-curated by Miller and Andrew Bolton, and book photographed by Tyler Mitchell, this year’s Met Gala celebrated not just Black style, but the styling of Black America.

The exhibition begins with the American context, the legacies of American slaves, early American portraits, and honors the legacy of Andre Leon Talley who, himself, had deep roots in the American South. It is with these details of geography in mind that, as we think longer about Black style and Black politics, we must take seriously the unique hyphenate African-American aesthetic, and the Black American South as a site of radical possibility where Black people are constantly refiguring their relationship to the American project and its roots.

Black aesthetics, Black style, Black Americana describe the way Black individuals carry their history, and what they have made of the deep colors that bind. It is a conversation between individual and collective, connecting collective consciousness to national conscience. Black Americana is the distance between minority and majority, between us and our cousins. It names the transatlantic tension between country co-authorship and bold freedom dreams. It has always been this way. Black self-fashioning, especially as it emerged through and beyond slavery as a critical performance of citizenship and taste, was an argument. It was an argument that Black people were capable of aesthetic judgement and perception itself. Despite the surveillance of slavery, we were capable of looking back.

This looking back came as a required condition of “taste,” or the evaluatory faculty needed in order to make aesthetic judgements. “Taste” itself was tangled with the construction of race and slavery, and was an Enlightenment ideal used to locate subjectivity, proper rearing, and personhood at individual and collective levels and therefore to justify imperial, colonial, and enslaving missions. From Shaftesbury to Heder to Kant, taste was politicized as a way to distinguish the “idiot and the savage,” from the refined, educated, fulfilled human being. It could be conditioned, but also reflected a perceived inherent condition of humanity; therefore in “taste,” there has always been both a liberatory quality in its possession and self-assured performance, yet a legacy of “taste,” as inherently unavailable to the “idiot or the savage.”

In David Bindman’s Ape to Apollo: Aesthetics and the Idea of Race in the Eighteenth Century (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2002), 51, the section “Universal or Discriminating Subject?: The Aesthetics of the Perceiver,” uses Daniel Chodowiecki’s Natural and Affected Behavior, 1777 as a visual site from which to analyze the Enlightenment making “the act of aesthetic judgment…a way of categorizing types of humanity.” During the Enlightenment, aesthetic perception and taste came to be considered “an inherent part of the human mind,” and “could, in that regard, be exercised by any human if they chose to do so, regardless of origin or background,” though paradoxically it was “regarded as something to be cultivated,” and “the defining attribute of ‘politeness,’ or gentility, which had been associated…with moral virtue.”

Taste was a way, in England, for the old aristocracy to defend against the unstable post-Civil War wealthy and a rising nouveau riche merchant class, and while Shaftesbury’s rigid sense of taste fell out of favor in Britain for a more “functional view of aesthetics,” in German-speaking countries his sense of “the relationship between outer and inner beauty remained a crucial problem of aesthetics and philosophy,” laying the foundation for the arguments of cultural conservatives globally, Herder praising Kant as “a German Shaftesbury,” and Herder being the thinker that most inspired Du Bois’s understanding of culture.

This infectious problem of aesthetic judgement “emerges in Kant’s pre-Critical writings, in Herder’s attempts to define an idea of culture, and most publicly in the early 1770s with the appearance of Laater’s sensationally successful Physiognomische Fragmente,” which pursued a qualification of the “nature of the soul,” by “scientific” study of the face. Against this scholarly backdrop, Black Dandyism has always been a strategic defense of Black humanity and an exercise of Black freedom as Black American styling was a critical argument of taste, the product of careful, strategic, and adaptive self styling that both miraculously and definitionally was never contingent on white approval.

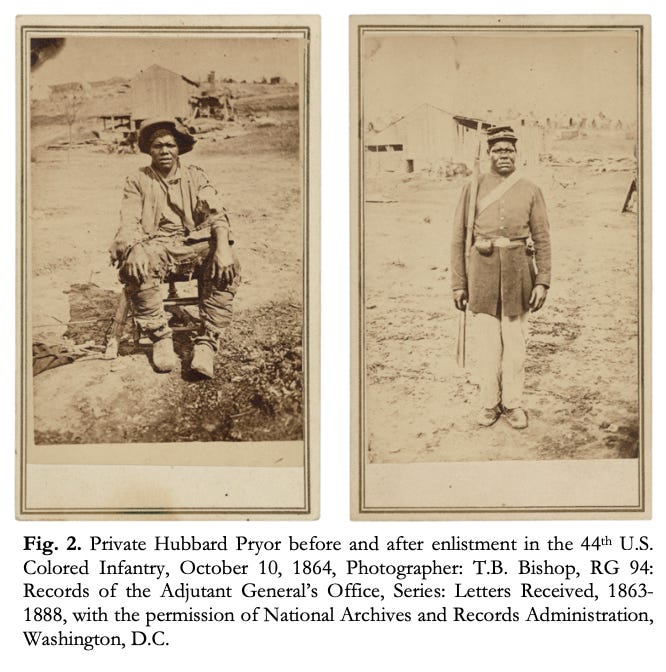

It is this self-styling and self-presentation, that forms the nexus of Harvard Art History Professor Sarah Lewis’s Vision and Justice which takes “conceptual inspiration,” from Frederick Douglass’s Civil War speech, “Pictures and Progress,” and its emphasis on “the transformative power of pictures to create a new vision for the nation.” In his time, Frederick Douglass was notably the “most photographed man in America during the 19th century,” photographed with stylish dress and his iconic hair, anchoring a long lineage of Black Americans using self-styling and presentation through photography to argue for their humanity and construct a counter archive to the work of slave daguerreotypes and the use of slave photographs to surveil and support phrenological arguments of subhumanity and cognitive underdevelopment.

Frederick Douglass understood that Black style was political, and that Black Americana was an argument to be made visually in the form of Black people not merely being observed, but looking good and looking back. Black dandyism is self-aware and critical. It lampoons white performances of racialized gentility, while constructing its own visual cannon of “looking sharp.” It is celebratory, it is stylish, it is smooth, it is cool.

Consider the work of Moses Williams, an enslaved profile cutter in Maryland, who shares my grandfather’s name. His life and work, the subject of former Harvard Art History Professor Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw’s close study “Moses Williams, Cutter of Profiles,” considering the complicated racial implications of his skillful nineteenth-century silhouette profiles in Charles Wilson Peale’s museum. Think of his 1802 self-fashioning of “Mr. Shaw’s blackman,” where in a completely black silhouette he fashions himself, “blackman,” with little obvious racial indicators yet “an animated bit of necktie peeking out from a high collar jacket,” a costume which “must be read as livery, rather than merely contemporary clothing.”

Then of course, there are the well-cited examples of black dandies like Julius Soubise, who is depicted in the 1772 satirical Mungo Macaroni print which depicts him with stockings, an elegant coat, a military cap, two styles of sword, and a smile. He looks like a caricatured aristocratic soldier, a Black-pastiche Batoni portrait, which makes sense considering that many white dandies were former soldiers, bringing military fashion and uniforms to the mainstream, alluding in their everyday style to the glory of combat. The term “macaroni,” itself was “originally coined to describe elite young Englishman freshly returned from the Grand Tour.”

These soldierly elements were a part of dandy culture, dually documented in William Heath’s satirical etching “Military Dandies or Heroes of 1818,” and this legacy lands with me in thinking of Black American dandyism through history, evoking images of Black slaves fighting in the Union Army, their uniforms being key in transforming them from “slaves into soldiers,” as strategy urging the white public to understand Black men as countrymen as opposed to barbarians.

This phenomenon is well-studied in Sarah Jones Weicksel “To Look Like Men of War: Visual Transformation Narratives of African American Union Soldiers,” in which she writes that “wearing a uniform, the white public believed, was the right of a man and citizen.”

This phenomenon is also the reason Black World War I soldiers came home and continued wearing their military uniforms stateside, hoping to garner respect as men and American citizens. This performance of Americana was so potent that it led to race riots across the Great Migration and the Western frontier and lynchings in the South, with many instances of Black men being attacked while in uniform. This is the revolutionary charge of Black Americana, exercised visually, performed in style.

It is easy to look to urban pockets of 20th century Black flourishing in locating and celebrating the Black dandy. There are the glamorous moments of the Harlem Renaissance and Motown, but when I think of black dandyism, it is the layering of dandyism’s militaristic flare, with Black labor, the Black church, and the everyday Black sense of elevated style that is linked to a visual lineage of Black Americana and draws me to rural pockets of Black life in the American South.

I grew up in Indianapolis, Indiana, a city I describe to people at Harvard as “Great Migration,” or “Generational,” such that I might conjure images of my childhood as both city and cornfield-adjacent, as both country and rust-belt urban in the way of St. Louis or Chicago, as city to those from the country and country to those from bigger cities, and as surrounded by a diversity of African-American people and a wealth of shared African-American culture. I grew up around Black people with more and with less than me, and we all played in the same little leagues, went to the same churches, and shared a foundation of collective culture and connected understanding.

This preface given, if I am talking to someone who understands the importance of geography, someone from the South or Black from the South or, especially, someone from Kentucky, I will then share that my family is also from Kentucky. Being so generationally African-American–I have four black grandparents that descend from American slaves–we are from a lot of places, but Kentucky is where we all packed in my Mamall’s van to return in late July. We drove the four hours to Russellville, Kentucky listening to Motown and John Lee Hooker, playing backseat games, not understanding both how common and how special of an experience this was.

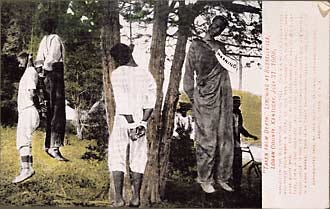

Russellville is one of many post-Civil War settlements of liberated Black Americans in border states, where, in the familiar isolation of these not-quite-deep South rural pockets, emancipated Black families came together to dream of an American kind of self-rule. That is Russellville’s Black Bottom, the historic Black neighborhood in this little country town beneath the hills off the interstate. Like many similar towns, Russellville is not only black. There is a history of racial tension, resistance, and close-living with rural white people, ex-Confederates, and the Ku Klux Klan, lawyer John Rhodes observing in 1944 that “it was as easy to raise a lynch mob in Logan County…as to drop a hat.”

Russellville was the confederate capital of Kentucky, and growing up, if we did talk about white people, which we didn’t often, I heard the story of John Jones, Virgil Jones, John Boyer, and Joe Riley lynched in 1908 for sympathizing with a sharecropper that shot his white employer in self-defense.

Growing up I saw in the Cooksey House Museum Museum–directly across the one-lane 8th Street where my Aunt Pat lived in her Kentucky Historical shotgun, where I flip-flopped in and out of every perpetually-open swinging door in the hot Kentucky summer–a painting of the note pinned to Virgil Jones’s body that all the Black peoples’ “lodges and halls better shut up and quit.” Images from the lynching now, curiously enough, are held by The Met.

There were the Frederick Douglas Lodge, Black town halls, Black schools, the Black church, and a whole lot of Black folk with big guns, and I remember vividly the story I was told to never repeat of my Pawpaw Moses and all his buddies shooting long guns up into the woods behind the family house when the Klan would meet in the giant hickory trees. Both my Pawpaws drove trucks, everyone talked through gold teeth with a marshy backwoods drawl that anyone unfamiliar would have no chance of understanding, and on Emancipation Day people would sing bluegrass on side streets and sell catfish fried right in front of you at sidewalk stands.

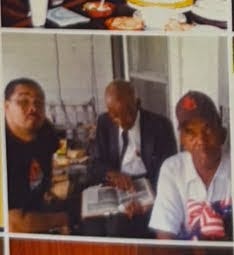

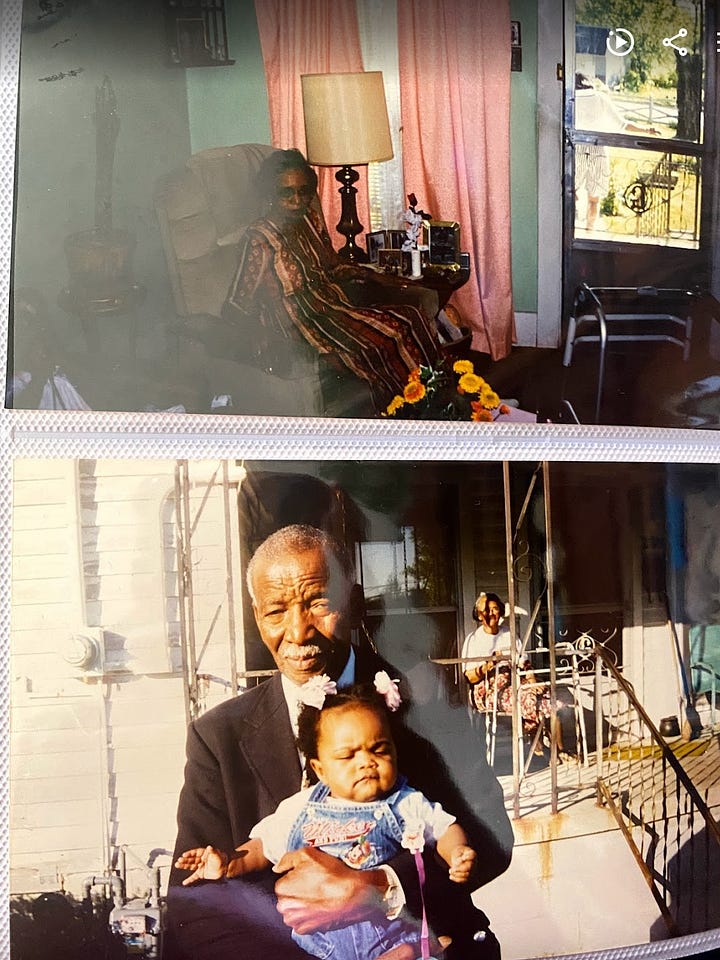

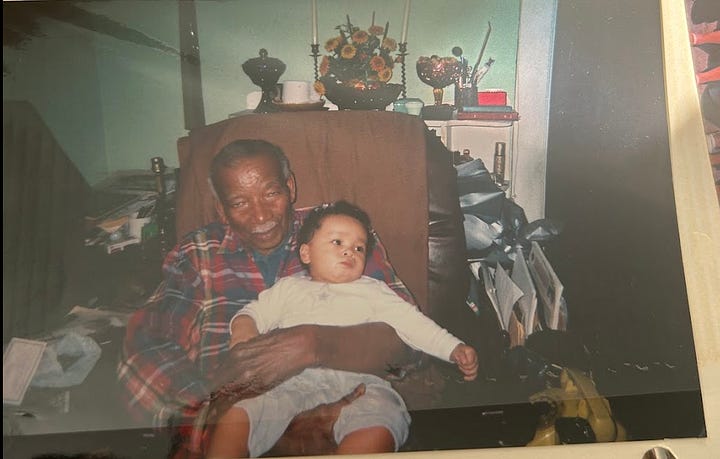

In Russellville, every Black house was historical and filled with stuff. Pawpaw Moses, my father’s father’s father, kept everything. He had endless records, communications from World War II, a rusty flatbed in his front yard, a motorcycle, postcards, Coke memorabilia from the factory, portraits, broaches, letters, meteors fallen from the sky, guns, and deeds. When he passed, we brought it all back up to Indianapolis and my Pawpaw would get it all out for me to sort through on the living room floor.

With such experiences in the country, it didn’t sit right with me when I watched social media influencer Cleotrapa say “the North taught the South how to dress,” a day before The Met. It simply wasn’t true. The tailored Black style I grew up seeing was in the details of Aunt Pat’s front gold tooth which let me distinguish her from the endless aunties and extended family I met in Russellville who all knew “Mose” (in Kentucky, the final “s” of my Pawpaws’ name was always silent). There was my Pawpaw’s bottom grill that spelled out my Mamall’s name, “Rose.”

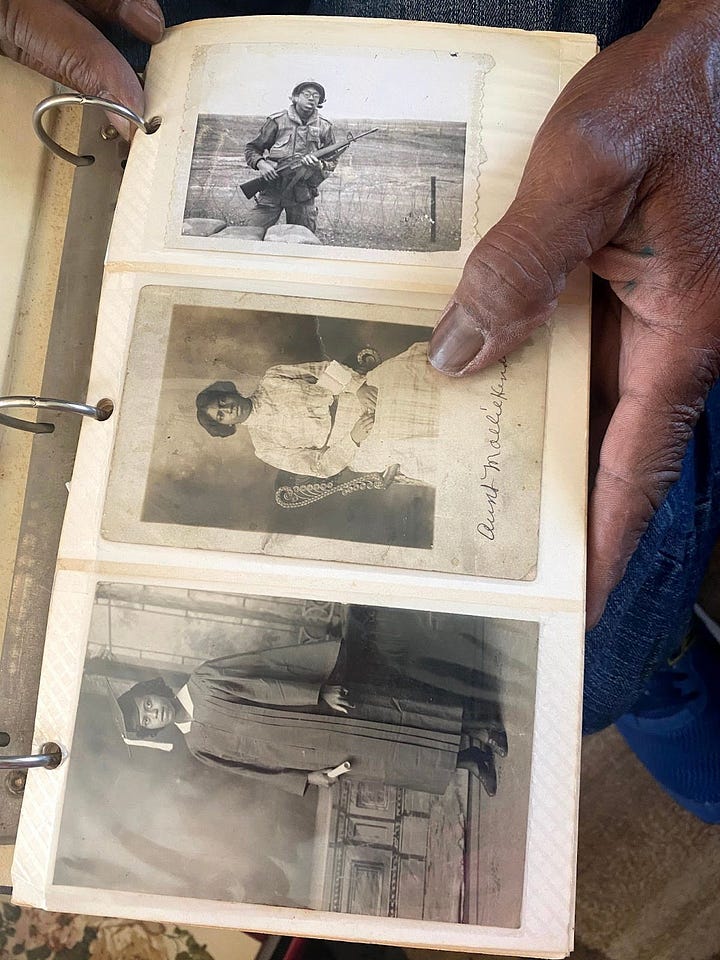

There was our Sunday clothes, my Mamall’s long nails and elaborate shawls, my Pawpaw’s telling his sons that they should always have a good belt and a good pair of shoes. There is my favorite photo of Pawpaw we uncovered in all the things from his childhood home. It is a young Moses Gaines in Baumholder, Germany, where he was deployed during Vietnam. It is an old photo of my Pawpaw, who, despite being recruited to play football at the University of Kentucky before any black boy had played in the SEC, chose to fight instead.

It is sepia-toned, a black and white image with rough-textured grain of a tall, strong, darkskinned Black young man in military uniform, positioned next to what appears to be the back half of an early-60s Volkswagen. Pawpaw stands at an angle to the camera, looking over his shoulder and down at the lense which shoots tilted up at him from a slightly lowered vantage.

We can see his name on his uniform, and he flashes a sly half smile. Head cocked slightly to the side in a suave contrapposto, his hand farthest from the camera holds a white clipboard and the other reaches across his body toward it, palms away from the camera, obscuring whether or not he is holding anything else. His pants are starched with a sharp crease visible near his ankles, and they cut off squarely above his shiny black boots. In the background, a large white and brick house backdrops him, with dandelion specks dotting the grass. I think back to the soldier dandies, and Julius Soubise’s swords. Here, my Pawpaw wears his uniform, yet stands authoritatively individual. Singularly stylish, an emblem of the Black soldier collective. His suave posture and assertive glance suggest the gentle authority and commanding presence for which I knew him in his life.

There’s another image of him I love while he was deployed, capturing him in plainclothes and sunglasses, a thick sweater, and similarly starch-creased tailored pants next to a uniformed friend. There are countless photographs of his father and uncles in uniform as well, and unlabeled military postcards from family I don’t recognize. There are also two striking portraits of Black boys in uniform holding big guns while they were deployed.

In this way, outfits like Coleman Domingo’s or Pharrell’s felt intimately familiar to me in their referencing the swagger of Southern Black Americans’ suits, and their elevation of fashion tropes by infusing them with outsized dignity, personality, and care. I loved Stormzy’s chicly undone Tom Ford suit which paid homage to the well-dressed Black man perhaps returning home from work, loosening his tie, and unbuttoning his shirt to reveal a white undershirt that is so much a staple of Black men from the South that it has received a colorful, less-than-politically correct moniker in the vernacular.

Details like Pharrell’s gold Invisalign grills or the starch pleat lines on Lewis Hamilton’s white pants felt like details I’d seen in Pawpaw’s old family photos. Pinstripe detailing in Nicki Minaj’s Thom Browne or the Zoot Suits of Zendaya or Khaby Lame or Chance the Rapper’s baggy suit and NOI-vibe felt like a celebration of the way Black men have remixed and remade their uniforms and their work clothes into symbols of economic and civic participation, taste, and style. Beyond this, Kerry Washington, with her big white hat and lace gloves, spoke to my memories of “Sunday best.” Across the carpet, there were details that interpolated the innovations of Black Americans and Black Southerners as they are directly linked to the way we have fashioned ourselves and our identity.

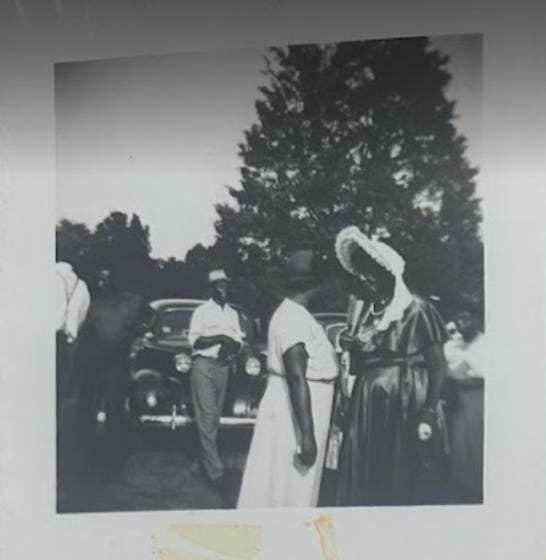

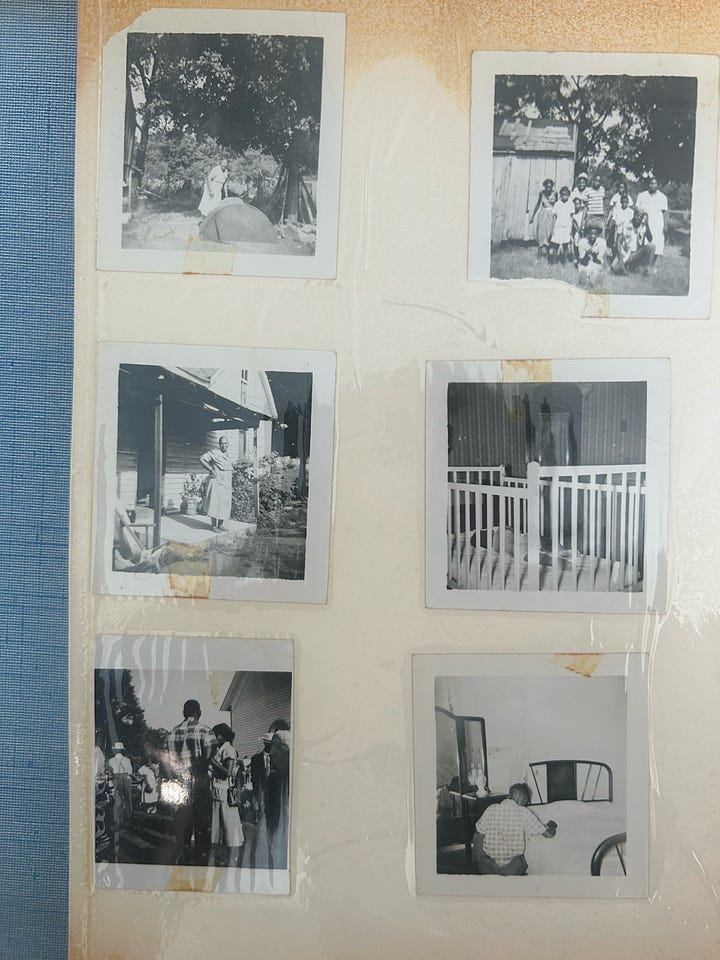

I remember a series of polaroids I found in Pawpaw’s photo books, one of the many days I made him excavate the family’s cabinets of archives. Somewhere in all of his stuff there is a pale blue photo binder of the most beautiful Black photography I’ve ever seen on Polaroid. It is a series of artfully-shot square photos from Russellville in vibrant black and white: ladies in white hats, long dresses, stockings and white shoes in front of a one-room praise house. There are children in bows, men in nice belts and nice shoes and stylish hats and ties. The timeless images show shotgun homes, cornfields, school steps, bedrooms, and blend a diversity of beautifully chromatic black bodies, their dark skin shining in the southern heat, backgrounded by the big Kentucky trees and their pinholes of flashing light.

There is a photo of a boy and a girl in a field wearing black and white, a ress and pleated pants, framed by a low hanging powerline like something of a Gordon Parks WPA photo. There is an intimate image shot from a bed of a Black man facing away wrapped in a sheet. There are people posted up posing with their dogs and shiny cars, there are smiles and candid shots and group formations and portraits, always shot angled up. There are places I remember in Russellville that still look the same today. As an art history major, I read these photos against my training. I am floored by the intimacy and careful composition, this vision of rural Black Americana that belongs to the Gaines’s and could still be lost to history. I wonder how many Black families have such a rich archive, I wonder how many Black artists lived and died without calling themselves “artists,” at all. My passion for Black Southern self-taught art is legitimized and reinvigorated.

These photos are sitting somewhere in a tub now with all of my Pawpaw’s other belongings, sorted following his passing just a couple months ago. Note here for any Gaineses reading this, where is this binder? Note again that Black families always maintain their own archive, and every time I’m back in Russellville I smile at the newspaper clipping of me in Indianapolis selling lemonade in front of the Korean hair store still pinned to the fridge. Note here how much I love my family and mourn the fact that the artist behind these stylized shots is lost to memory. I should have asked my Pawpaw. Maybe I’ll ask Aunt Pat this summer, though, artist notwithstanding, these anonymized artifacts of black creativity, styling, and vision–as we see, as we capture, and as we anticipate being seen–remain, and they remain as nameless archetypes, capturing a whole community, history, heritage, and way of life.

I think of the image from Pawpaw’s of a Black man in a navy uniform, crisp pure white, holding a long gun across his torso as he faces the camera with a stoic, pensive gaze. The corners of his mouth extend, not quite smirking, refusing to frown. The incomplete shingling of the house diagonally behind him creates a backdrop of pattern and line. There is a texture and rhythm to the composition of the image, offset by the subject’s straight-facing gaze, disrupted by the diagonal of his gun.

I think, then, of Amy Sherald–who, too, was at the Met Gala in a Fear of God tailored suit of rich fabric combinations, draped in a wool overcoat with a deep crimson broach–and her larger-than-life “American Sublime,” which opened at the Whitney a month ago. I consider For Love, and for Country, her tender and timeless Black subjects who are as American as they are Black, who are as individual as they are archetypal sites through which we, viewers, might locate our own heritage and identity. I think of A God Blessed Land (Empire of Dirt), one of her many life-sized, American-realist insertions of the Black American back into the canon, depicting a Black man posted up on a John Deere, overalls cuffed to reveal his shiny black boots. I think of her Mother and Child, the mother’s straw hat, the baby on her hip.

Amy Sherald tends to the “wonder of what it is to be a Black American” and outsizes the beautiful and familiar instances where our intimate, complicated, catenated lives are nothing short of high art. American Sublime centers “everyday Black Americans, compelling in their individuality and extraordinary in their ordinariness,” and it is under this umbrella that both her portrait of Michelle Obama and her portrait of Breonna Taylor might be co-curated. The world of the Black Dandy, of the American Sublime, of the stylish Black soldier, of Pawpaws and Mamalls, is a vision of Black Americana where Michelle Obama is necessarily in conversation with Breonna Taylor, as Sherald’s brush calls us to notice. Giving them both their due meditation, capturing them both dignified and frozen in time, Sherald pushes us to consider how Black Americanness is a paradox of the ordinary and the extraordinary, and a web of interlinked legacies.

Growing up in Indianapolis, I always understood what my godmother meant when she said “I could as easily be her as she could be me,” as she modeled treating every Black woman with the deferential respect of family, whether she was Associate Headmaster or on the maintenance staff of my private high school. This is the magic of being Black American, African-American even, generationally so, from a Great Migration pocket where almost every other Black person I know is familiar, in every sense of the word, whether they went to an Ivy League school, Division One, community college, or to jail. We all are only a stroke of luck, of fortune, a series of blessings, an episode of history away whether we are on the Kennedy Center Stage being named the National Youth Poet Laureate, on Pop the Balloon Indianapolis, or on the news.

This connection, of “Superfine” to American Sublime, to Black Americana, I believe, is worth lingering on at present so we might be able to understand better aesthetic strategies that will carry us through the political landscape and back home to whomever we must answer. As a Black American, this doesn’t mean leaving, or abandoning this country’s creedances, this means I must work through, honoring my culture and my heritage, such that I might return to the America that is mine. To the rolling hills in a freedom town, to being barefoot eating catfish and hot sauce and big tomato slices on white bread while watching basketball tournaments of Black boys outside in Russellville listening to NBA Youngboy and sweating out my silk press.

There are things that are so Black that they do not have to be named as such. Americana is one such thing. Black Americana is dandyism, is style, is swag, is church hats and fresh cornrows, it’s gold teeth and jays, it’s baby hair and eco styler, it’s lotioning your knees. It is the way we push culture forward and lift everyone up. It is the way we two-step and the joy of being with our people that’s instilled in us as early as when our mothers or fathers or Mamalls or Pawpaws first teach us how to clap on beat.

From there, patriotism is so Black too. I mean the kind of patriotism that James Baldwin describes in Notes of a Native Son (1955) declaring “I love America more than any other country in this world,” linking it, “and, exactly for this reason,” to his second clause, “I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.” This Black patriotism, this Black American-ness is a positionality, an orientation toward the project of America that we must take seriously in recalibrating our resistances, codifying our community spaces, and turning back inward toward our own institutions, dreams, and identity under a seek-and-destroy administration that wants for us nothing of the sort.

We must discover a way through the language of our national politics. For me, in the United States, this begins with being forceful about what is mine. My two framed, thirteen-folded flags and the POW/MIA coin I carry with me from my Pawpaw’s funeral is mine. My family’s sacrifices are mine, Pawpaw’s guns, my daddy’s house out in Clermont, the trees, the deer, the rolling hills, mine. The bluegrass, the John Lee Hooker, the Motown, the country music, mine, yes! Our church home is mine, chitterlings are mine, Russellville is mine, and the right to call myself a proud American is mine. I agree with my cousin who is an Army Sargent, my Pawpaw, my Pawpaw Moses, and all his brothers; I agree with the black dandies, with Andre Leon Talley, with Dapper Dan; I agree with Amy Sherald that this is worth fighting for. One way or another.

As a poet, as an artist, I believe we must understand these instances as connected, and politics as visual. In lieu of any poem I’ve written, I will share one of my Pawpaw Moses’s many. I found this poem in an old typewriter I kept from the Russellville house, it is still loaded in the carriage and–in the context of his other poems meditating on the Great Depression, the CCC, his service, his brothers’ service, and all his family’s service–I interpret it in the context of the military and the nation.

This poem is how I interpret Black dandyism, the American sublime, Black art, Black Americana, and the imperative that all this celebration and warmth become a tangible location of resistance and protection for Black people in America at present. The poem is simply one single line repeated, formatted across three stanzas of couplets: “Now is the time for all good men to come to the aid of their party.” Not the Democratic Party, but the project of Democracy itself. Not just American politics, but African-Americanness. My love for Russellville and the South, because it is my cultural homeland, and because there is nowhere else for me and all my loved ones to go. Now is the time. Now is the time. Now is the time.

Any thoughts? Christ cannot return soon enough when a 12 foot Bronze statue depicted as over-weight/obese, with no bra, fake-hair, resting bitch face, and the stereotyped hand on hips is considered art. https://torrancestephensphd.substack.com/p/introducing-leticia-quaisha-sha-nay