From Legacy to Liability: The Crisis of Capitalist Imitation Among Black Women in Power

How Billionaire Dreams Are Betraying Black Feminist Legacies

The Price of the Tiffany Diamond: A New Dilemma

On a fall day in 2021, a gleaming Tiffany & Co. advertisement featured Beyoncé draped in a 128-carat yellow diamond – a jewel mined under brutal colonial conditions in 19th-century South Africa. Touted as the first Black woman to wear the storied gem, Beyoncé’s participation was meant to symbolize Black achievement. Instead, it sparked backlash: fans and critics accused her of helping to “sanitise a ‘blood diamond’” with a “dodgy colonial history.”

The singer’s mother rushed to defend her, but the damage was done – the moment revealed how even an icon of Black excellence can be entangled in the legacy of exploitation. That image of Beyoncé – powerful, wealthy, and partnering with a luxury jeweler – captures a growing tension around prominent Black women and the price of corporate alignment.

Today, many Black women who came of age in Generation X and now hold cultural or political power are celebrated as success stories. Yet their success often comes packaged in billionaire capitalism, corporate sponsorships, and individualist “inspiration” that stand in stark contrast to the collectivist, anti-capitalist spirit that buoyed earlier Black freedom struggles.

This essay explores how figures like Michelle Obama, Oprah Winfrey, and Beyoncé – and even rising political stars like Rep. Jasmine Crockett – have navigated (and at times compromised) the legacy of radical Black politics in exchange for the liability of capitalist imitation.

What does it mean when a generation of Black women trades in socialist or leftist ideals for visibility and wealth? And what are the consequences for young Black women watching from the wings?

We will examine the narratives and choices of these women in power, critique the co-opting of Black spaces by corporate interests, and spotlight alternative models rooted in mutual aid and collective liberation. In doing so, we seek a balance of critique and care – calling in our sisters with love, even as we call out the systems that constrain us.

From Radical Roots to Respectability

The tension between radical roots and respectable success is not new in Black politics – but it has sharpened in the era of Black women breaking glass ceilings. Historically, Black freedom movements have been profoundly anti-capitalist and communal.

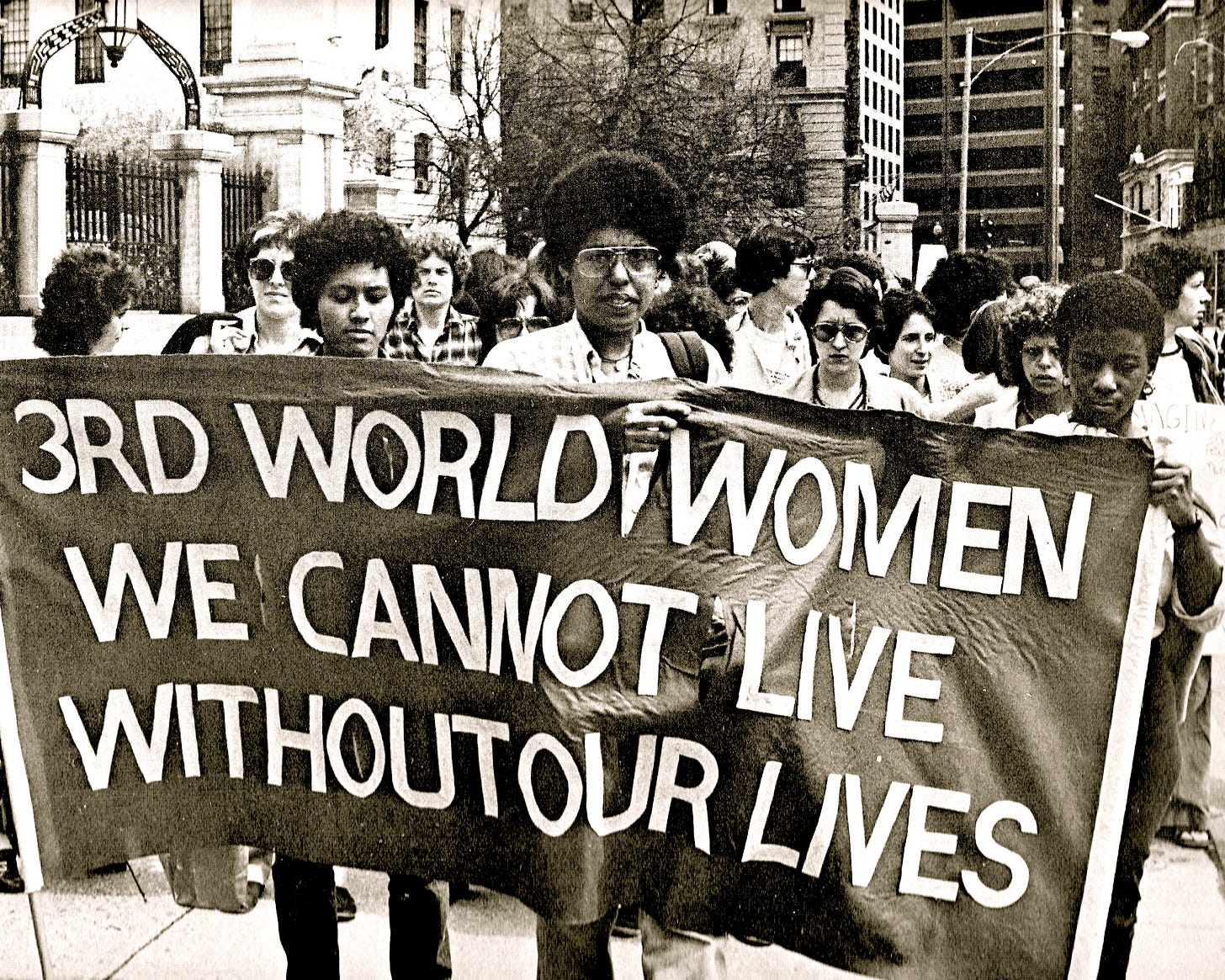

The 1977 Combahee River Collective Statement, a cornerstone of Black feminist thought, declared that “the liberation of all oppressed peoples necessitates the destruction of the political-economic systems of capitalism and imperialism as well as patriarchy”, affirming a socialist, collective ethos. Black women activists from Ella Baker to Angela Davis carried forward traditions of community organization, anti-imperialism, and economic justice.

Fast forward to the late 20th century: African American women of Gen X inherited these legacies of resistance but also new opportunities to ascend in mainstream institutions. Many pursued careers in law, media, and politics, often becoming “the first” or “the only” Black woman in elite spaces. As they rose, some embraced a different philosophy of change – one less about overthrowing systems and more about succeeding within them.

The result has been a cohort of highly visible Black women whose politics skew toward accommodation and personal empowerment rather than structural transformation. They carry the symbolic weight of “Black girl magic” and “Black excellence,” yet the substance of their politics may align more with neoliberal capitalism than radical Black liberation.

This shift from legacy to imitation can be seen in the trajectories of household names. Their journeys are often lauded as inspirational – but a closer look reveals how the pull of capital and corporate influence steers them away from the very liberatory politics that cleared their path.

The Self-Help Gospel of Michelle Obama

Michelle Obama came into national prominence as an embodiment of multiple hopes: a product of Chicago’s South Side community organizing tradition, a Princeton and Harvard-educated professional, and the first Black First Lady of the United States. Many admired her poise under pressure and her ability to “live as a symbol” of progress.

After leaving the White House, however, Michelle Obama’s public persona took a notable turn. Her memoir Becoming (2018) shattered sales records and her subsequent stadium book tour felt more like a motivational speaking circuit than a political call to arms. In her memoir and its follow-ups, Obama leans heavily into personal stories of perseverance and advice on overcoming self-doubt – what one review acidly called “self-empowering bromides” that reveal “the limits of her politics.” In other words, she has mastered the art of inspiration, while sidestepping overt ideology.

Critics noted that Becoming was “laden with inspirational symbolism and patriotic platitudes”, carefully avoiding any language that might ruffle the mainstream. Rather than challenging readers to demand more of society, Obama often urges them to work on themselves.

This apolitical self-help gospel may comfort a broad audience, but it glosses over systemic barriers. For example, instead of foregrounding policy solutions for injustice, she shares affirmations about confidence and personal growth. It’s empowerment repackaged as individual uplift – a kind of polished Lean-In feminism with a smile. Michelle Obama herself has acknowledged she’s not a “political” person; indeed, one observer quipped that the secret to her political success is that she “hates politics”.

What a dangerous statement to make for young Black girls without abortion rights, drowning in student loan debt, as if our hatred of politics will change their daily and lethal impacts on our everyday lives.

To be clear, there is nothing wrong with encouraging personal growth or telling one’s story. Michelle Obama’s warmth and authenticity have endeared her to millions, especially Black women who rarely saw themselves reflected in the halls of power.

However, the politics of personal narrative come at a cost. By framing progress in terms of individual achievement and resilience, Obama’s post-White House brand aligns neatly with American meritocracy myths – and avoids confronting the entrenched inequalities that a more left-leaning Michelle Robinson might have challenged.

The First Lady who planted a kitchen garden as a gesture of healthy living now sells out arenas with pep talks, not demands for structural change. Her journey from community-oriented lawyer to global celebrity author highlights how easily the system co-opts even those with grassroots beginnings. The question lingers: as she inspires young women to “become” their best selves, does she also inadvertently encourage them to accept the system as it is?

Billionaires, Brands, and the New Black Capitalism

If Michelle Obama represents the self-help strand of this phenomenon, Oprah Winfrey and Beyoncé represent its billionaire capitalist apex. They are two of the most famous Black women on the planet – self-made in the popular telling – and both have built business empires that rewrite what power looks like for Black women. And yet, their careers illustrate how Black excellence can be harnessed to reinforce the very economic system that marginalizes most Black people.

Consider Oprah, often affectionately called Momma O by fans – a talk-show host turned media mogul who became the first Black woman billionaire. Oprah’s story of rising from poverty in Mississippi to owning a network is undeniably remarkable. But scholars and cultural critics have long pointed out the ideological underpinnings of her brand.

Media professor Janice Peck argues that Oprah’s entire enterprise “reinforces the neoliberal focus on the self,” legitimizing inequality by promoting a vision of selfhood tailor-made for a world of winners and losers. On The Oprah Winfrey Show, personal problems were to be overcome with positive thinking; social ills like job insecurity or health care costs were reframed as individual challenges you could conquer if only you adjusted your mindset.

Oprah famously rejected “victimization” narratives in the 1990s, insisting that people “move on” and lift themselves up, a philosophy she credits with bringing her both spiritual fulfillment and great wealth. In practice, her media platform became a pipeline for self-help gurus and spiritual entrepreneurs telling us that “external conditions don’t determine your life. You do.”

This relentless positivity and emphasis on personal responsibility resonated with millions – but it also neatly aligned with neoliberal capitalism’s demands. As one commentator put it, “Oprah is appealing precisely because her stories hide the role of political, economic, and social structures.”

Her feel-good narratives make the American Dream seem attainable by sidestepping how racism, class, or policy shape outcomes. The result is a depoliticized brand of Black success, comforting to the status quo. Oprah’s feel-good capitalism goes down easy: for a generation of viewers, she modeled Black female empowerment without the messy need to challenge corporate power or public policy.

Indeed, Oprah even lent her considerable influence to establishment causes like weight-loss industries and pseudo-spiritual consumerism, at times appearing to suggest that buying the right products or books could cure deep social anxieties. In sum, Oprah’s rise shows how a Black woman can break every glass ceiling – and yet leave the house of glass intact.

Beyoncé, a different kind of mogul, took the music world by storm as a teen and by her thirties had become a one-woman corporate conglomerate. With hit songs and visual albums that increasingly embraced pro-Black iconography, Beyoncé won praise in the 2010s for injecting messages of pride and resilience into pop culture. Her Lemonade album referenced Malcolm X and police brutality; her 2018 Coachella performance paid homage to HBCU band culture and Black history.

Fans and scholars debated: Was Beyoncé perhaps a capitalist and a revolutionary? Or was her radical chic just aesthetic? The answer became clearer as her business deals piled up. She launched Ivy Park fashion with Adidas, inked multi-million-dollar sponsorships, and carefully curated her image as not just an artist but an aspirational brand.

The Tiffany ad fiasco underscored the limits of Beyoncé’s representation-as-progress approach. In that campaign, Beyoncé and Jay-Z posed as the ultimate power couple – a Black King and Queen fronting a venerable white luxury brand. The imagery was striking, but so was the irony: in trying to signal Black success by wearing a priceless diamond, Beyoncé inadvertently reminded the public of the blood-stained origins of such wealth.

As critics noted, “diamonds are a capitalist’s best friend,” with a “sordid history” of colonial exploitation and marketing manipulation. For all her personal virtuosity and pro-Black messaging, Beyoncé had aligned herself with a company seeking to rebrand via a Black icon while doing little to confront its own history. It was a textbook example of what happens when “representation and being ‘seen’” are treated as substitutes for actual change: the surface looks empowering, but underneath, nothing fundamental is challenged. Tiffany & Co. even pledged scholarships to HBCUs – a feel-good gesture – but the underlying power dynamics (who profits from Black consumer desire, and who truly benefits) remained unaltered.

Oprah and Beyoncé are different women in different fields, but both illustrate how Black women in power can be celebrated for breaking barriers while simultaneously entrenching capitalist norms. They have become, in effect, billionaire exceptions held up to prove that the system works – a narrative that can actually undermine calls for systemic change.

Their wealth does not trickle down to the masses of Black women struggling with student debt, healthcare, or low wages; in fact, their success stories can sometimes be used to silence those struggles (“if Oprah and Bey made it, why can’t you?” the thinking goes). Meanwhile, younger Black women may internalize the idea that liberation looks like owning a piece of the empire rather than dismantling it.

Black Media, Brought to You by Coca-Cola

This capitalist co-optation isn’t just about individuals – it extends to Black media and cultural institutions that once carried an ethos of empowerment. One need only step into the Essence Festival of Culture in New Orleans or tune into an awards show on BET to see the paradox in full color: celebrations of Black womanhood and achievement awash in corporate branding.

At Essence Fest – one of the largest gatherings of Black women in the country – the presenting sponsor is Coca-Cola and the list of major sponsors reads like a Fortune 500 roster: AT&T, L’Oréal, Target, McDonald’s, and more. What began in the 1990s as a one-time “Party with a Purpose” to uplift the community has evolved into an annual extravaganza “presented by Coca-Cola®”, complete with product booths and branded experiences at every turn.

To be fair, sponsorship money allows these events to take place at scale, and companies now recognize the economic power of Black women consumers. But the heavy presence of fast food and soda giants raises eyebrows. McDonald’s and Coca-Cola plaster their logos across events meant to inspire wellness and empowerment in Black communities – communities that also suffer disproportionate rates of diabetes, heart disease, and diet-related illness.

The irony is hard to ignore: one moment you’re in a seminar on Black women’s self-care, the next you’re handed a free Big Mac coupon. The message becomes muddled as corporate interests wrap themselves in the veneer of Black empowerment. When media platforms like BET (Black Entertainment Television) – founded with a mission to represent Black voices – rely on advertising dollars from firms that might not have Black folks’ health or liberation at heart, it inevitably influences content.

There’s a reason BET’s programming historically shied away from hard-hitting political critique in favor of music videos and reality shows; upsetting sponsors is bad for business. Essence, too, has to walk a line: its magazine might run articles on financial literacy or beauty, but not overt condemnations of, say, predatory banking or exploitative labor practices.

The presence of “brand activism” also complicates things. In recent years, corporations have learned to sprinkle the language of Black Lives Matter and Black Girl Magic into their marketing. We see Nike running empowering ads with Black female athletes and hashtags like #SayHerName, or McDonald’s launching a “Black & Positively Golden” campaign targeting Black youth.

Superficially, this representation is positive – it’s nice to be seen and courted as a market. But as scholars note, “representation alone cannot redress capitalist business practices that exploit people of color globally.” A feel-good ad does not equal fair wages or ethical supply chains. Thus, when Black media and events lean on these sponsors, they also risk becoming mouthpieces for “woke capitalism” – promoting an illusion of progress while the structural conditions remain unchanged.

None of this is to say that BET or Essence are malign actors; often, they’re doing the best they can within a capitalist media landscape. However, it’s crucial to recognize how the boundaries of acceptable discourse are policed by the need to remain palatable to corporations.

The result is a kind of implicit censorship – a narrowing of the revolutionary imagination. The radical politics of previous Black media figures (think of the 1970s Essence magazine issues that covered Third World solidarity, or the old BET political talk shows) give way to a glossy empowerment-lite message: you can have “Black excellence” as long as it’s brought to you by Coca-Cola and doesn’t question the broader system.

Performative Politics on the Public Stage

The phenomenon isn’t limited to pop culture and media – we also see it in politics. As more Black women assume elected office, it’s worth asking: do they carry forth a new paradigm of leadership, or do they sometimes mimic the spectacle-driven, personality politics of the mainstream?

The case of Rep. Jasmine Crockett offers a cautionary tale. Crockett, a Dallas Democrat and Gen X Black woman making waves in Texas (now in Congress), has quickly gained a reputation for her fiery style. She’s unafraid to clap back at Republicans and “bite back” in viral moments. Progressive constituents want to see that passion. But when does passion slide into performative excess?

At a Human Rights Campaign dinner in 2025, Rep. Crockett let loose a zinger about Texas Governor Greg Abbott, referring to him as “Gov. Hot Wheels” – a jab at his use of a wheelchair. Some in the crowd laughed, but many others – including disabled activists and even some allies – cringed.

The comment was widely denounced as “despicable” and “shameful”, handing Abbott’s supporters an easy way to deflect from his policies and claim the moral high ground. In the quest to own the opponent, Crockett’s quip veered into ableist territory, betraying the inclusive values progressives claim to uphold. It was a stark example of how optics and outrage can overtake substance.

Crockett’s rise mirrors that of other media-savvy politicians who realize a blunt soundbite can fundraise better than a nuanced argument. In an age of social media, the temptation to prioritize performance over policy is strong. For Black women politicians in particular, there’s pressure to appear tough and unbossed – to channel the cultural archetype of the no-nonsense Black auntie who tells it like it is.

Crockett herself has leaned into this persona, reveling in moments that go viral on Black Twitter. To her credit, she often does speak hard truths about racism and injustice. Yet the “Hot Wheels” episode revealed a troubling side effect: in trying to emulate a kind of swaggering power (long modeled by brash male politicians), a Black woman leader can end up punching down or reinforcing harmful norms. That’s a far cry from the principled, compassionate leadership envisioned by Black feminist theorists or community elders.

The incident invites a deeper reflection on what we want from Black women in power. Do we want them to simply imitate the traditional halls-of-power antics – trading barbs, chasing clout, amassing donors, perhaps cutting backroom deals – or do we want them to transform leadership itself?

Crockett’s misstep suggests that without a strong grounding in accountable, movement-based politics, even our sheroes can lapse into the performative, individualistic style that capitalism rewards. It’s a symptom of a system where making a spectacle often counts more than making a difference.

Consequences for Gen Z: Chasing the Wrong Dream?

What do these high-profile examples mean for the generation coming up behind them – especially Gen Z Black women? On one hand, today’s young Black women are some of the most politically engaged and outspoken we have seen. They are leading racial justice marches, excelling in academia and arts, and bringing an intersectional lens to issues like climate change and LGBTQ+ rights.

Many openly critique capitalism and demand systemic change, keeping alive the radical tradition. On the other hand, they are growing up inundated with the images of Black success crafted by the likes of Oprah, Beyoncé, and corporate “Black girl magic” campaigns. The danger is that they receive mixed messages: that liberation means climbing the ladder and securing a seat at the table, rather than flipping the table altogether.

It is not hard to find Gen Zers who equate progress with representation at the top. The logic goes: if we can get more Black women CEOs, more Black billionaires, more Black girls in luxury fashion ads – we’ve made it. Indeed, some young influencers brand themselves as mini-Michelles or the next Beyoncés, focusing on personal branding, entrepreneurship, and securing bags (money) as the ultimate goal.

“Within a capitalist consumer society, the cult of personality has the power to subsume ideas, to make the person, the personality into the product and not the work itself.”

— bell hooks

The ethos of the “Girl Boss” – basically a woman who unapologetically pursues profit and power – has trickled into some corners of Black social media. Gen Z grew up seeing a Black First Lady and multiple Black female celebrities as moguls; the normalization of Black women in elite positions can inspire confidence, but it can also feed the illusion that individual ascension equals collective advancement. We risk raising a generation that measures success not by how many people they lift up, but by how high they climb.

Moreover, the emulation of capitalist success can lead to burnout and disillusionment. Not every Black girl will become a millionaire motivational speaker or pop superstar – in fact, very few will. What happens when ordinary young women pour their energy into chasing these models and hit the harsh realities of racism, sexism, and economic inequality?

Some will internalize failure (“I didn’t hustle hard enough”); others may adopt cutthroat attitudes that alienate them from their communities. The focus on personal achievement can erode the sense of solidarity. We already see some young people dismiss activism as “performative” or futile, retreating instead into the pursuit of personal success or the escapism of consumer culture. If all the prominent role models are touting corporate partnerships and luxury lifestyles, who is modeling the value of community care or collective action?

Fortunately, Gen Z is not a monolith. Many young Black women are skeptical of their elders’ accommodation with capitalism. They ask pointed questions: Why celebrate Black billionaires when Black poverty is still rampant? Why should I be excited about Kamala Harris as VP if she upholds policies that harm marginalized people?

This generation has seen the streets erupt in protest and is acutely aware of the system’s failures – from climate crises to police violence. In some ways, they are more primed to critique the status quo than Gen X was at their age. The challenge is ensuring they have alternative models to look up to – examples of Black women wielding power differently.

Reclaiming Power: Mutual Aid and Collective Models

If the current trajectory of Black women’s leadership is tilted too far toward capitalist imitation, what might a course correction look like? The answers can be found in the very communities that have been here all along, practicing mutual aid, collective economics, and radical politics often under the radar. It’s time to shine a light on those models – not as utopian fantasies, but as living traditions that are already delivering for our people.

One such model is the resurgence of mutual aid networks, many led by Black women, that sprung into action during the COVID-19 pandemic. When government systems failed and wealthy elites retreated to their enclaves, it was grassroots organizers – mothers, nurses, teachers, neighbors – who pooled resources to feed families, deliver medicine, and keep each other afloat.

These efforts echoed a long history: Black communities have practiced mutual aid since at least the 19th century, forming benevolent societies, giving circles, and cooperatives to survive under racial capitalism. The principle is simple: we take care of us. Instead of waiting for wealth to trickle down, mutual aid works horizontally, building power and resilience at the community level.

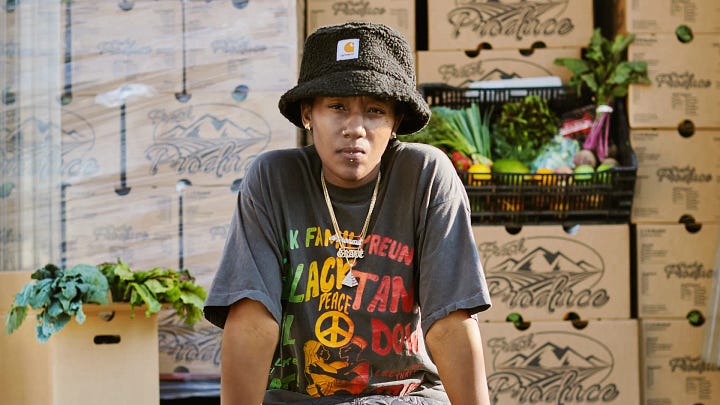

Take the story of Lauren Halsey, a young visual artist from South Central Los Angeles. In early 2020, Halsey was designing an Afrofuturist community center – an arts and cultural hub to imagine liberated Black futures. Then the pandemic hit. Seeing her neighbors facing hunger and hardship, Halsey pivoted: she turned her art project into a community food distribution hub. Through her Summaeverythang initiative, she began sourcing fresh organic produce from local farms and giving it away for free every week.

By mid-2020, they were distributing over 600 boxes of produce weekly, funded largely out of Halsey’s own pocket (using proceeds from her art sales) and donations. Collaborating with local chefs and volunteers, she kept this operation going at a scale of $80,000 a month, essentially building a miniature food justice economy in her neighborhood.

Halsey describes the project as “a mutual aid effort, community gathering, and an art practice rolled into one.” In her eyes, this work is not charity – it’s an extension of her creative vision for a self-determined Black community. By meeting basic needs, she is also feeding imaginations: showing people that care, not profit, can drive our solutions.

Halsey is not alone. Across the country, other Black women are leading cooperatives and liberation projects that prioritize collective well-being over individual wealth. There are Black-led credit unions popping up to serve the underbanked, farming co-ops in urban food deserts, and healing circles for mental health that operate outside the for-profit model.

Activists in groups like Black Youth Project 100 and the Movement for Black Lives explicitly call for investing in communities rather than jails and weapons – channeling funds to education, housing, and restorative justice. These efforts often lack the spotlight, but they carry forward the true legacy of Black feminist politics: the belief, as the Combahee River Collective said, that “work must be organized for the collective benefit... and not for the profit of the bosses.”

The irony is, while billionaire celebrities capture headlines, it’s these cooperative, community-led efforts that have been most effective at saving Black lives and building power during crises.

Imagine if the energy spent idolizing one-in-a-million superstars was redirected to supporting a million mutual aid projects. Imagine if instead of asking corporations to validate us with sponsorships, we held them to account and built our own institutions.

The alternative models are here – they just need to be resourced and replicated. This is not to say every Black woman in power must quit her job and start a nonprofit; rather, it’s a call for a mindset shift. We can leverage our influence and platforms to pour into collective advancement, not just personal gain. And we can demand of our role models that they do the same: invest in their communities, speak up for radical change, and use their clout to challenge capitalism’s excesses, not just exploit its opportunities.

Black Art Spotlight: Visions of Liberatory Futures

As we chart a path forward, art and storytelling will be crucial in helping us imagine what liberatory Black futures can look like. It’s fitting, then, to end on a hopeful, generative note by spotlighting Black artists whose work illuminates new possibilities beyond the confines of capitalist imitation. These are creatives who, through visual art, literature, or performance, are offering blueprints of freedom rooted in love, justice, and collective thriving.

One shining example is the literary realm of visionary fiction and Afrofuturism. Author N.K. Jemisin, for instance, has crafted science fiction worlds that center Black and brown peoples not just surviving, but resisting oppression and reordering society. In her award-winning novels, ordinary people discover extraordinary powers of community and reshape broken worlds into better ones.

Jemisin’s imagination directly challenges the narrative limits set by white, capitalist patriarchy – she literally writes new destinies where cooperation and equity triumph. As one critic noted, her stories highlight the “potential to resist oppression and reorder the world — even when entire societies have been structured to limit and exclude.”

When young Black women read Jemisin (or Octavia E. Butler, or Tananarive Due, or Nnedi Okorafor), they aren’t just escaping into fantasy – they are learning to dream past the boundaries of what this society tells them is possible. This kind of artistic inspiration fuels movements; it gives people the courage to demand what others call unrealistic.

In the visual arts, we see talents like the aforementioned Lauren Halsey and many others using art to reclaim Black space and time. Consider artist Simone Leigh, who won the highest honor at the 2022 Venice Biennale for her sculptures celebrating the agency of Black women throughout history. Leigh’s work, steeped in Black feminist consciousness, imagines a future by drawing from ancestral knowledge and communal symbols – from towering bronze busts of Black women that exude strength, to installations that evoke the spirit of collective rituals.

Each of these artists offers a piece of the liberatory puzzle. They’re not billionaires or corporate darlings (at least not primarily); they are unapologetically Black creators who draw from the well of Black experience – past, present, future – to offer visions of wholeness. By engaging with their work, we nourish the part of ourselves that capitalism tries to starve: the radical imagination.

Conclusion: Charting a New Legacy

“From legacy to liability” – the title of this essay suggests that something precious from our past has been turned against us in the present. The legacy in question is the heritage of Black radical, socialist, and communal politics that uplifted generations. The liability is the way that heritage is being undermined by a new ethos of capitalist imitation among some of our most visible leaders.

But as we have explored, this crisis is not irreversible. Awareness is the first step: by naming the pattern, we can begin to break it. We can celebrate the accomplishments of Black women in power without swallowing the myth that their wealth or corporate partnerships are the pinnacle of our progress. We can critique our faves lovingly, holding them (and ourselves) to a higher standard that measures success by collective gain rather than just personal glory.

For progressive readers – whether Black or allies – the charge is to support and amplify those who are practicing liberatory politics now. It means redirecting our attention and resources: can we spend as much time boosting mutual aid funds or cooperative businesses as we do buying celebrity merchandise? Can we push our media to cover grassroots organizers with the same fervor as it covers celebrity gossip? Each of us has a sphere of influence, however small, where we can shift the narrative.

Most importantly, we must invest in the rising generation of Black women and girls, not as future moguls, but as future movement-builders. They deserve mentors and models who will teach them that caring for the community isn’t just a nice extracurricular, but the very essence of leadership. They should know that it’s okay to reject a seat at a table that demands you lose your soul – you can build a better table. And they should feel that being unapologetically Black can also mean being unapologetically anti-capitalist, feminist, disabled-friendly, queer-affirming, and dedicated to justice across the board.

In closing, the story of Black women in power is still being written. We stand at a crossroads where one path leads to simply reproducing the existing order with Black faces at the top, and another path leads to truly transforming that order with Black principles at the core. The latter path is harder, requiring sacrifice, imagination, and solidarity – but it is the path that honors our legacy and secures a livable future for all.

As the saying goes, lift as you climb – but perhaps it’s time to question the climb itself, and focus on lifting each other in place. In the spirit of our foremothers who toiled in collective struggle, and in honor of our daughters who deserve a freer world, let us turn back from the mirage of capitalist success and reclaim the liberating power of community.

The next chapter can still be one of redemption: a generation of Black women in power who choose to turn their backs on the master’s tools, and instead, build a new house where everyone can flourish. That is a legacy worth fighting for, and one that will never become a liability.

Until next time,

Marley