Survival and Erasure

My great-great-grandmother’s face peers out from a sepia-toned document that marks her legal arrival into American life. Issued by the Superior Court of Barnstable County on December 15, 1944, it records her as a 49-year-old “female” of “former nationality: Portuguese”—a sterile legal classification that obscures far more than it reveals.

In the tiny photograph affixed to the certificate, Eugenia wears a faint, resolute smile. This slip of paper was her ticket into American civic life, but it also signals the tightrope she was forced to walk—between legal belonging and lived exclusion.

But it was her daughter-in-law—my great-grandmother Dorothy—who would carry that tightrope walk into the next generation. Family lore holds that in the early 1960s, during President John F. Kennedy’s administration, Dorothy “passed” as white to secure work as a maid on the Kennedy Compound in Hyannis Port. It was an act of quiet rebellion and heartbreaking compliance all at once – a survival strategy in a world that left her no easy choice.

Mid-century America imposed immense constraints on Black and Cape Verdean women like Dorothy. In Massachusetts, as elsewhere, domestic work was one of the few jobs available to women of color, butt even that required an acceptable presentation.Dorothy, a Cape Verdean descended from immigrants from an Atlantic archipelago off the coast of Africa, understood that opportunity came easiest when she was seen as “Portuguese” or mistaken for a white European Survival meant erasure. To feed her family and keep a roof overhead, she had to sand down the edges of her identity until she fit neatly into America’s simplistic racial puzzle.

On duty at the Kennedy home, she wore a crisp uniform and a neutral smile, speaking only when spoken to. She let her employers assume what they wished about her ancestry. Every “yes, ma’am” and “no, sir” was delivered in practiced English, never betraying the Creole language of her childhood. Each day on the job, she navigated the dissonance of dusting fine furniture in a home of Camelot-level privilege while hiding the truth of her own lineage. It was a privilege to serve in that rarefied world, and yet it was a profound loss, too – a daily denial of the Cape Verdean blood that flowed through her veins.

My great-grandmother Dorothy looked white, and she knew it. It let her move through certain spaces with less friction—like working on the Kennedy Compound—but it never sat right with her. She hated being called white. To her, that label wasn’t a privilege; it was a denial. A denial of her family, her heritage, her truth. She may have passed to survive, but she never passed to belong. And in a world that constantly tried to erase the nuance of Cape Verdean identity, being called white felt like just another form of disappearance.

I often imagine the emotional contortions this required. Dorothy’s body surely kept the score of those anxieties – the quickened pulse whenever someone looked too closely, the tension held in her shoulders from maintaining polite silence. In the evenings, when she returned to her modest home, perhaps she removed her whitening mask like a starched apron, exhaling into the lullabies of her youth.

The certificate her mother-in-law earned – that coveted proof of citizenship – was both blessing and burden. On one hand, it affirmed their family belonged legally to this country. On the other, it came at the cost of social belonging; to be accepted, Dorothy had to disappear in plain sight.

That naturalization paper became a metaphor passed down in our family—a symbol of how legitimacy in America often demands the suppression of one’s true self. Eugenia gained a nation. Dorothy navigated its terms by cloaking her identity. Her story, kept quiet for decades, speaks volumes about the overlapping oppressions that Black and Cape Verdean women faced in mid-20th century America – forced to dim their light just to survive in the shadows of opportunity.

Carving Out Dignity

If Eugenia’s life was defined by constrained survival, her son – my great-grandfather Joseph “Joe” Brito – spent his life carving out spaces of dignity within those constraints. Joe was born in New Bedford, Massachusetts, in 1925, the son of Cape Verdean immigrants Eugenia and her husband, Joseph Sr. He grew up in a nation that viewed him as a Black man, regardless of his nuanced heritage.

As a young man, he enlisted in the U.S. Army during World War II. And while he fought for freedom abroad, at home, the military remained deeply segregated—its promise of liberty shadowed by the same racial boundaries he had always known.

Joe was shipped off to the Pacific theater – family whispers later confirmed that he saw combat in the brutal 82-day Battle of Okinawa – and was discharged in 1946 with the rank of corporal. In uniform, he served a country that granted him citizenship but not full equality. Yet, he served with pride, perhaps believing, as his mother did, that claiming American identity could open doors for the next generation.

But when Joe returned from war, America did not exactly welcome Black veterans with open arms. GI Bill benefits were often denied or hard to access for men of color, and the Cape Verdean nuance of Joe’s identity did not spare him from Jim Crow’s reach (even in the North, de facto racism was rife). Still, Joe pushed forward, determined to wrest a decent life from the opportunities available.

He settled in Hyannis, not far from where his mother had labored in secret. For most of his working years, he drove trucks for Hyannis Sand & Gravel, hauling the literal building blocks of the postwar boom. On those dusty New England roads, Joe became known as a reliable hand, even if to some he was just another Black laborer.

He carved out dignity load by load, proving his worth through toil. When he finally retired in 1988, it was with quiet fanfare – a framed commendation, handshakes from coworkers who’d known him for decades, and the satisfaction of having provided for his family through pure grit.

But there is so much more to Joe than his labor. The constraints of society did not define the limits of his joy. In the evenings and on weekends, Joe transformed a corner of his garage into a personal workshop. There, amid the scent of sawdust and engine oil, he indulged his passions.

He was a gifted woodworker, whittling scraps of wood into functional art – a lovingly carved stool for a grandchild here, a repaired porch railing for a neighbor there. He also adored antique cars; an old 1940 Buick sat in that garage, and Joe spent countless hours under its hood, coaxing the engine back to life while blues music crackled from a dusty radio.

These hobbies were more than pastimes – they were acts of quiet resistance. Each time he sanded a piece of mahogany to a satin finish or polished the Buick’s chrome, Joe was asserting control over his world. In a society that often tried to diminish him, he created small realms where he was the master, where beauty and order flowed from his own hands.

At home, Joe was the beloved patriarch of a growing clan. He and my great-grandmother Dorothy (herself the daughter of Cape Verdean and Portuguese parents) were married for 68 years, a partnership marked by resilience and humor. Together they raised six children.

The older relatives say that in Joe’s house you’d hear English at dinner and catch snippets of Kriolu – Cape Verdean Creole – while we watched WWF every night. He taught his children and grandchildren the values that had carried him through war and hard work: humility, perseverance, and love.

By the time I knew him as an elderly man in the 2000s, Joe had a quite grace and a storyteller’s charm. He rarely spoke of the war – he never told me directly that he had braved Okinawa’s shellfire. Instead, he shared gentler memories: the cherry blossom trees he saw in Japan, the turquoise waters off Hawaii where his ship refueled, the spicy foods he tasted in foreign ports.

Through those stories, he awakened my own curiosity—about the world, about him, and about the histories folded quietly into the lives of those who came before me / my relatives who came before me

Through those stories, he awakened my own curiosity—about the world, about him, and about the histories folded quietly into the lives of those who came before me / my relatives who came before me.

“Read. Imagine. Then go see it for yourself,” he would tell me with a wink, planting the seed that my mind could travel even if our world had borders.

Though Joe never boasted, one of his quiet satisfactions was seeing the next generations rise higher. One of his grandsons – my cousin, Gary Brito – followed in Joe’s footsteps into the Army. Joe lived long enough to see Gary become a Colonel in the U.S. Army. In fact, Colonel Gary Brito would later become the first Cape Verdean American to command Fort Benning in Georgia – a milestone that would have been unimaginable in Joe’s youth.

He now serves as the Commanding General, United States Army Training and Doctrine Command. At Gary’s promotion ceremony, I like to imagine Joe—standing at attention, pride shining through his quiet resolve—as his grandson shattered barriers that had long held back soldiers of color.

In Joe’s gentle smile that day, you could glimpse the arc of progress: a legacy of constraint transformed into inspiration. He had given his descendants the foundation – through his service, labor, and love – to strive for heights that he himself was barred from. Joe Brito spent a lifetime making do with less than he deserved, yet he infused every inch of that life with dignity. In the shade of systemic injustice, he carved out joy and left a legacy of hope.

Neither Black Nor Portuguese

The stories of Dorothy, Eugenia, and Joe do not exist in isolation – they are threads in the larger tapestry of Cape Verdean history, a tapestry woven with invisibility and resilience. Our family’s journey, with all its quiet adjustments and strategic silences, echoes the experience of many Cape Verdean Americans. Cape Verdeans began immigrating to New England in the 19th and early 20th centuries, forming enclaves in coastal towns like New Bedford, Nantucket, and Providence.

They came from an island culture born of creolization – a blend of African and Portuguese lineage – and landed in an America obsessed with binary racial categories. Where did people like us fit in a society that insisted you were either Black or white, African or European?

The uncomfortable answer: nowhere neatly. So, our elders learned to shapeshift. Many Cape Verdean families denied their African background and started telling people that they were Portuguese to navigate the color line.

My own family did this when necessary. Passing as Portuguese or just “foreign” could mean the difference between getting a job or being shut out, between sitting at the front of a segregated bus or being forced to the back. Dorothy’s charade as a white maid was one such case of this wider practice. By portraying herself as a Portuguese woman, she could slip through some of the racial barriers of mid-century Massachusetts, enjoying small freedoms denied to those marked “Black.”

Yet, passing as white or embracing a Portuguese identity was a fraught bargain. It offered certain privileges—but often at the cost of deep psychic wounds.. It did not fully shield Cape Verdeans from racism. Relatives who passed still endured whispered slurs and suspicious glances from neighbors who sensed they weren’t quite “white.”

Historian Danielle Porter Sanchez recounts how her Cape Verdean father, raised to identify as Portuguese, was still chased and harassed in Boston as a “nigger,” leaving him perplexed and traumatized. In our community, no amount of straightened hair or adjusted accent could completely erase the African heritage written in our brown skins and high cheekbones – our neighbors and coworkers often saw it, even if we didn’t speak of it.

And so, many of our elders lived in a painful in-between. They hid one part of themselves to survive, while that very part – their Blackness – remained an open secret quietly scorned. Within families, this created rifts of silence. Some elders refused to teach Kriolu to their children, fearing it would mark them as “other.” Some never spoke of Cape Verde at all. In fact, in one account, a young woman’s mention of Cape Verde to her grandmother caused such discomfort that the grandmother abruptly hung up the phone.

For decades in America, Cape Verdean heritage was something often “silenced continuously from generation to generation” – a ghost presence, felt but seldom named.

On official papers, we were often flattened into reductive categories. U.S. immigration and census records variously labeled Cape Verdeans as “Portuguese” (by nationality) or “Negro” (by race), rarely acknowledging the distinct identity we carried. I think back to a 1930 Nantucket census page I once saw in an archive: it listed a Cape Verdean family, the Lobos, as the only “Negroes” on their street, even though they hailed from Cape Verde and likely spoke Portuguese Creole at home.

Did the family self-identify that way, or did an official just assign them a race? We will never know. But the result is emblematic: our people rendered invisible or lumped into someone else’s story.

On Eugenia’s own naturalization certificate, the paradox leaps out – her “color” is typed as “black,” but her nationality is “Portuguese.” A Black woman of a Portuguese colony, she gained citizenship in a country that only grudgingly began to accept people of African descent. It hadn’t escaped her that just decades earlier, U.S. law outright barred non-white immigrants from naturalizing; timing, and the technicality of being a Portuguese subject, worked in her favor. It hadn’t escaped her that just decades earlier, U.S. law outright barred non-white immigrants from naturalizing; timing, and the technicality of being a Portuguese subject, worked in her favor.

In that single document, the government tried to reconcile what America couldn’t in society: a Cape Verdean who was both African and European, Black yet legally European – a living challenge to the binary logic of race in America.

While Cape Verdean Americans navigated this racial liminality in the U.S., across the ocean, our ancestral homeland was undergoing its own profound transformation. In the 1950s and 60s, as Dorthoy and Joe were building their lives in Massachusetts, Cape Verde was still a colony of Portugal – still yoked under European rule.

But during this time, a brilliant agronomist-turned-revolutionary named Amílcar Cabral was galvanizing a movement for independence. Cabral understood that the fight was not only military or political but also a fundamental struggle for identity.

“Culture is simultaneously the fruit of a people’s history and a determinant of history,” he declared, emphasizing that reclaiming one’s culture is a revolutionary act.

Cabral and his comrades in Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde fought to affirm that we were neither second-class Portuguese nor an invisible people, but a proud African nation with our own language, music, and story.

In 1973, Cabral was assassinated, but the seeds of liberation bore fruit: by 1975, Cape Verde won its independence from Portugal. For the first time, the world officially recognized the Republic of Cabo Verde.

I often wonder what that meant to elders like Eugenia. By 1975 she was in her 80s, having lived a life of careful self-effacement. Did she allow herself a private moment of pride, hearing that the islands of her birth were free at last? Did Joe, then a middle-aged father, feel a swell of validation knowing the land his parents came from now stood on its own feet?

Perhaps it was bittersweet – they had gained a country on the other side of the ocean, but in America they were still fighting to be seen.

Nonetheless, Cabral’s legacy reverberated quietly in our diaspora. He taught that “national liberation is necessarily an act of culture”, and indeed, over time many Cape Verdean Americans began to reclaim our unique identity with renewed vigor.

By the late 20th century, Cape Verdean clubs, festivals, and churches flourished in New England. We learned to celebrate our morabeza – our warm hospitality – and our coladeira music openly, even as we also took our place in the broader African American struggle for civil rights. The two strands of our identity, African and European, once seen as a source of in-between confusion, became a source of strength and rich culture.

In my own family, this shift from silence to voice has been a defining legacy. My father, who grew up during the 1970s, saw the last gasp of the old “don’t ask, don’t tell” approach to heritage, but also the rise of Black pride and Afrocentric education. He was a fifth-generation Cape Verdean American, and he took to heart the idea that embracing one’s full history is a path to freedom.

“Choice, not chance,” he’d often remind me.. For him, identifying proudly as a Black Cape Verdean American was a choice – a deliberate reversal of Eugenia’s endured silence.

And so, in our home, unlike in Eugenia’s day, Black stories, experiences, and media surrounded us I grew up hearing both the funaná music of Cabo Verde and the jazz records of African America. I learned about Harriet Tubman and about Queen Nanny; about Martin Luther King Jr. and about Amílcar Cabral. The constraint that shaped my ancestors’ lives has, in a way, become the fuel for my own scholarship and activism.

I’ve come to see telling our story – with all its painful nuances – as a form of healing. Every time I speak or write the words “Cape Verdean American,” I am breaking a silence that my great-great-grandmother felt compelled to keep.

I am making visible what history tried to erase.

A Library of One’s Own

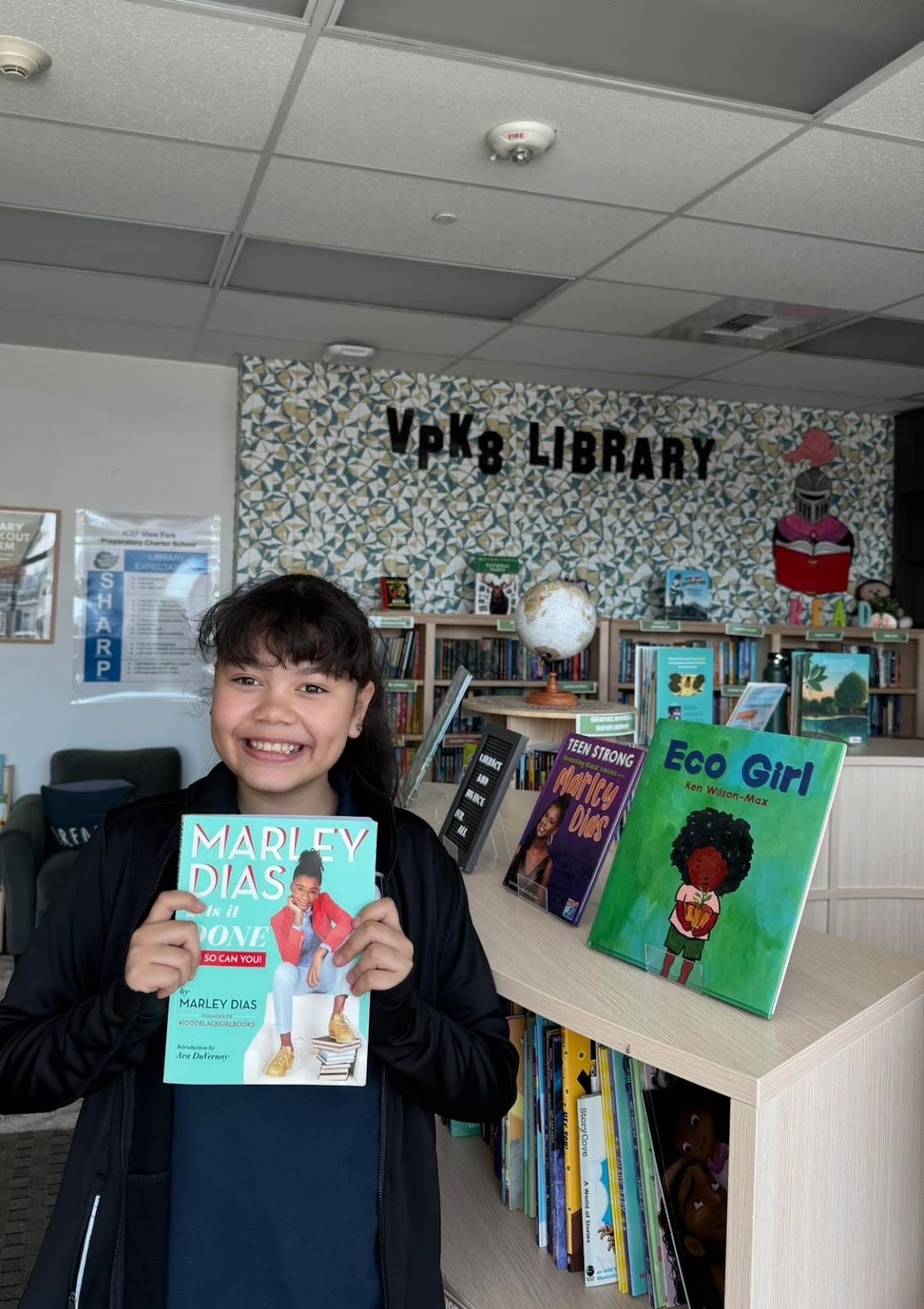

On a bright California morning in May, I will stand in a buzzing schoolyard in South Los Angeles, witnessing a scene that would have made Eugenia’s heart skip a beat. Children in navy-and-black uniforms will gather around a newly refurbished library at View Park Prep K-8 Elementary.

Above the doorway, bold letters will spell out the name of the library’s benefactor – The Marley Dias Library. That is my name.

At 20 years old, I will see a childhood dream take tangible form: a library carrying my name, filled with books I will help curate for these kids. I will feel a joyous weight on my shoulders – the embrace of generations past, and the responsibility that comes with being seen.

Where Eugenia once clutched her certificate as proof of belonging, I will run my fingers over the engraved plaque by the entrance, proof that I belong without question, that I have a place not by assimilation but by celebration.

This will be a full-circle moment of reclamation, visibility, and joy.

I will close my eyes amid the laughter and chatter, and I will picture five generations of my family like links in a human chain, leading up to this threshold.

I will imagine Eugenia in her faded house dress, standing quietly at the back of the library and marveling at the colorful book spines in English, Portuguese, and even a children’s book or two in Kriolu. In this library, nothing about our heritage will need to be hidden.

I will see Joe – Grandpa Joe with his Schlitz hat – bending down to examine the low shelves where picture books about brave little Black girls will await eager hands. He will grin, the wide grin I remember, and I will know he’s happy that these children won’t have to travel the world as he did to glimpse its wonders; the wonders will be right here in books, free for them to explore.

I will see my father, standing tall and proud, his eyes moist with the realization of what this means: a Dias family member’s name publicly and positively emblazoned on an institution of learning. For him, it will validate the choice to cherish our full identity and share it with others.

When I cut the ribbon to officially open the Marley Dias Library, the crowd of students will cheer, not fully grasping the historical layers behind this day. But I will. Constraint, citizenship, legacy. These themes will echo in my mind.

Eugenia’s constraint meant she could only dream of a moment like this, never live it. Joe’s citizenship – earned in a segregated army and a lifetime of labor – laid the groundwork for his descendants to claim our place in America. Their legacy will live in me.

And it will live in this library, which will stand as a beacon of the very things they hungered for: knowledge, recognition, freedom. This library will be more than a room full of books; it will be a sanctuary of stories, including our own. It will be the kind of place I longed for as a little girl who loved reading but seldom found Black girls like me in the pages of library books. I will name this book drive and library project in part for that little girl – to ensure that no child feels invisible when they scan the shelves. Every story of a young hero of color that a student pulls from these shelves will be a testament that we belong in the narrative.

As the children file in to explore the books, I will linger — running my hand over the spines of titles I will help handpick. Here will be a book of folk stories from the very islands Eugenia left behind. And there, Brave Like Me, a story of a child whose great-grandpa fought in a war – a gentle nod to Joe’s service.

In the fiction section, a graphic novel about a Cape Verdean-American superhero will sit beside the latest Diary of a Wimpy Kid. The juxtaposition will make me smile; it will mean our culture stands proudly alongside the mainstream, no longer hidden. On one wall, there will be a framed poster of Amílcar Cabral, and underneath it a quote in bold letters: “Tell no lies, claim no easy victories.” I will include this as a message to the students – and to myself – that the journey to justice and truth is ongoing. Cabral’s words, which guided a revolution, will now watch over a new generation learning to read and think critically.

In that jubilant moment, I will understand viscerally that we have broken a cycle. The strategic silence that once cloaked my family’s identity will have given way to voices – my voice and the voices of these children shouting out book titles and new discoveries.

The erasure that defined Eugenia’s era will be answered by the visibility of my name on this school library and the representation within its books. We will have transformed constraint into creativity, citizenship into community, and legacy into light. My family’s journey – five generations from a colonial island to a California school – will show that history is not a straight line of progress, but a winding road of sacrifice and love. Eugenia could not be openly Cape Verdean in 1960, so I could proudly be Cape Verdean-American in 2025. She passed so that I could stand in the light.

Before I leave the library, I will take out Eugenia’s naturalization certificate from a protective envelope I will bring along. I will show it to a small group of curious students. They will gaze at the old document, at the black-and-white photo of the woman who, I will explain, is my great-great-grandmother.

e page. In the quiet of the new library, I will whisper a thank you: to Eugenia, to Joe, to Cabral, to all of my ancestors.

Their journeys will have created my path. Their legacy will be my inheritance. From constraint, we will have found freedom; from erasure, we will have built a living legacy. And in this little library in View Park, the light of that legacy will shine for generations to come.

☆ This story was inspired by the resilience of five generations of a Cape Verdean American family, and informed by historical accounts of Cape Verdean immigration, racial “passing,” and the life of Amílcar Cabral. It is a reflection on how the body and spirit carry the memories of constraint, and how each generation can transform those burdens into bridges toward visibility and pride. Edited by

.