Heavy is The Inheritance

How Black families turn memory, movement, and Mondays into masterpieces.

Mondays get a bad rap. I try to treat them like an old friend who shows up unannounced- sometimes inconvenient, always a little dramatic, but honestly, who would I be without them?

See, in my family, grief isn’t just a sad story. It’s more like a secret ingredient in the soup- a little bitter, a lot rich, and impossible to leave out if you want the real flavor. I used to think the blues was something I could outgrow, but grief? Grief is an inheritance. It’s the family group chat you can’t mute, the playlist you didn’t make but somehow know every word to.

So, what does it mean for grief to live in your body, not just your mind? And how do you carry it without letting it crush your Monday vibe? That’s what I’m exploring today, with a little science, some family stories, a dash of Baldwin , and a whole lot of Black art.

Sticky Notes on DNA

To be nerdy for two secs, epigenetics is science’s way of saying, “Hey, your ancestors’ drama might actually be in your genes-but not in a scary, sci-fi way.” Trauma doesn’t rewrite your DNA, but it does leave sticky notes all over it, changing how you react to stress, love, and, Mondays.

Researchers have found that the children of Holocaust survivors, descendants of enslaved people, and folks who’ve lived through major trauma often have bodies that act like they’re always bracing for the next plot twist. Black Americans, for example, show higher rates of stress hormone issues, such as cortisol, and are more likely to deal with anxiety, depression, and hypertension.

But here’s the thing: Black families have known this forever. Before scientists had terms, our grandmothers were already measuring our silences, side-eyes, and sighs. We didn’t need a lab to tell us that grief lingers. We just needed Sunday dinner.

The Weight We Carry

If you think my family tree is all somber faces and sad tiny violins, you haven’t met us. Our reunions are equal parts therapy session, comedy special, and history lesson. Take Uncle Herky — Buffalo Soldier, Purple Heart, and the only person I know who could make jag and recite military code simultaneously. His grief was a quiet thing, tucked into the crease of his smile, but he still showed up for every reunion.

Aaron, my cousin, had a laugh that could fill a room and a knack for disappearing right when it was time to do dishes. His story is complicated — incarceration, substance use, a system that never played fair — but he taught me that sometimes survival looks like a joke told at the wrong time, or a dance break in the middle of chaos.

Uncle Jamie was the glue, the hype man, the unofficial DJ of family gatherings. Losing him was hard, but his playlists live on. And Great-Grandma Dorothy? She made cachupa that could heal just about anything, including a broken heart or a bruised ego.

Our grief shows up in the way we hug — quick, tight, and with a little extra squeeze for good luck. It’s in the food, the music, the way we tell stories (and embellish them). Sometimes we inherit grief not just by hearing the stories, but by feeling the silences between them.

When I read The Things They Carried by Tim O’Brien in 11th grade, I remember feeling like he had somehow peeked into our family photo albums. O’Brien writes about soldiers carrying not just weapons, but letters, good luck charms, pieces of home — and the invisible weight of fear, memory, and loss. That’s what it’s like for us, too. We carry more than what people see. We carry jokes to cover the scars, recipes that taste like home even when we feel far away, playlists that remind us who loved us first. The weight isn’t just sorrow. It’s everything that makes us stubborn enough, joyful enough, and wild enough to keep living.

Grief doesn’t get to steal the spotlight. It dances with us — and sometimes, if we’re lucky, it even sings backup.

Dancing With Our Ghosts

Here’s where it gets fun: Black bodies are living archives. We keep history alive in our dance moves, our recipes, our side-eyes, and our art. From ring shouts to line dances, from blues to house, we remix survival into celebration.

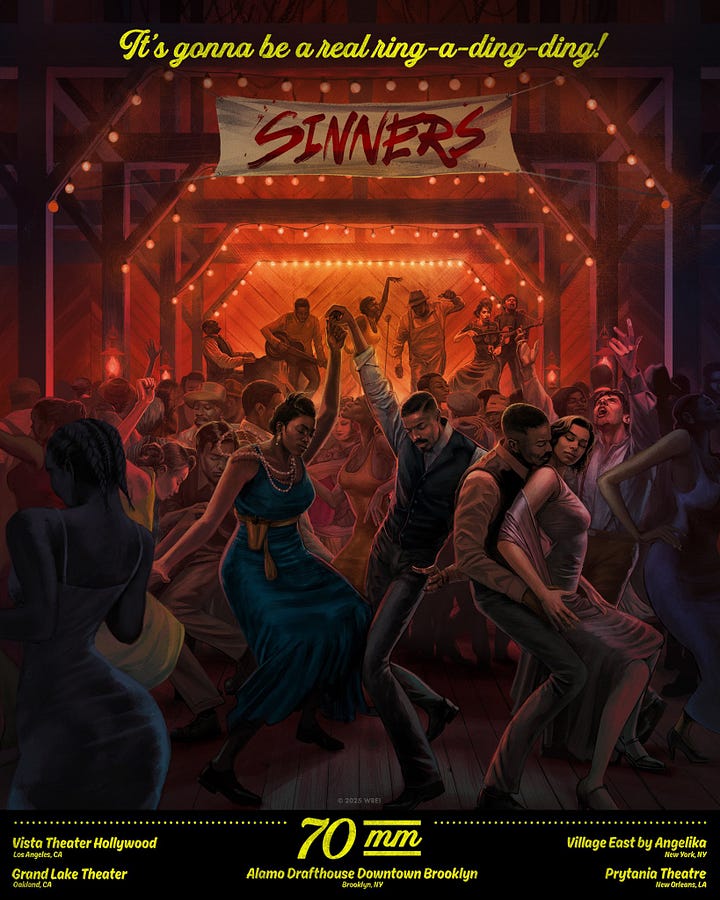

Speaking of remixing, let’s talk about Sinners, Ryan Coogler and Michael B. Jordan’s new film. Imagine a juke joint in the Mississippi Delta, 1932—music, sweat, and a guitar that might be haunted by the blues legend Charley Patton himself. The film isn’t just about vampires. It’s about how Black folks turn grief into ritual, movement, and art. The dancing isn’t just for show—it’s survival. Michael B. Jordan’s characters carry generational weight on their shoulders, but they still find time to laugh, love, and fight for joy.

Coogler draws direct inspiration from Ernie Barnes’ 1976 painting The Sugar Shack—one of the most iconic depictions of Black communal life in American art. The Sugar Shack is all undulating bodies, stretched limbs, and music made visible: a painting that captures the feeling of being fully alive together, even when the world outside tries to grind you down.

Barnes, who was a professional football player before he became a celebrated painter, developed a style that he called "neo-mannerism" — emphasizing exaggerated movement, intimacy, and the body’s ability to carry emotion without words. His figures are almost always faceless but hyper-expressive through posture and rhythm, just like Annie Lee’s. In The Sugar Shack, joy is kinetic. It travels through elbows and knees, through the lean of a shoulder or the dip of a hip. It says: We are here. We are moving. We are more than what the world sees.

By echoing Barnes’ composition in Sinners, Coogler isn’t just nodding to art history—he’s placing his film inside a long, powerful tradition of Black visual storytelling where survival is mapped onto the body. Where grief isn’t denied but danced through. Where memory isn’t still; it’s moving, sweating, laughing, glowing.

Black art has always been more than decoration.

It’s documentation. It's theory. It’s refusal. And it's joy.

“You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read.”

James Baldwin

Or, in this case, you watch. Sinners is a reminder that our pain doesn’t vanish; it just finds new shapes—sometimes as horror, sometimes as a two-step.

In my family, survival is a group project. Uncle Herky’s uniform, Aaron’s jokes, Dorothy’s kitchen—all of it is proof that we don’t just survive, we thrive.

Healing Isn’t Erasure

Let’s bust a myth: Healing isn’t about “moving on.” It’s about moving differently. I’ve tried therapy, yoga, journaling, activism (#1000BlackGirlBooks shoutout >.<), and I’ve learned that healing means giving your grief somewhere to live-preferably with snacks and a playlist.

Great-Grandma Dorothy’s complicated identity taught me to define myself on my own terms. I don’t let grief freeze me in place. I let it fuel me. I remember, but I also dance, laugh, and keep it moving. Mondays included.A Portrait of Our Mondays: Annie Lee’s Blue Monday

If grief is an inheritance, then so is the exhaustion we sometimes feel trying to outrun it. One of the most explicit pictures of this lives in Annie Lee’s iconic painting Blue Monday.

Painted in the 1980s, Blue Monday shows a faceless Black woman hunched over on the edge of her bed, struggling to will herself into another week. No mouth, no eyes—just the curve of her back, the sag of her shoulders, and the whole weight of living pressing down on her. Annie Lee, who once worked as a chief clerk for a railroad company, knew firsthand what it meant to wake up heavy-hearted but still have to move anyway.

I see Blue Monday and all of us—every Black girl who ever woke up too tired to explain why, every woman who stitched a smile over her sadness just to get through the day. The facelessness of Lee’s figures isn’t absence—it’s invitation. It lets any one of us step into that moment.

And yet... we resist being trapped there.

Even though Blue Monday tells the truth about how hard it can be to rise, it’s only part of the story. Annie Lee didn’t stop painting after Monday morning. She painted us dancing, laughing, playing spades, singing at church, loving up on each other at family cookouts. Grief may sit with us at the start of the week, but it doesn’t get the final word. Movement, music, and memory do.

Blue Monday reminds me that we are allowed to acknowledge the weight without being crushed by it. We can look at that quiet moment on the edge of the bed and say, Yes, I know that feeling—and then still rise up, stretch out the hurt, and move toward something lighter.

We are not just survivors of grief. We are makers of new mornings.

Black Art Spotlight: Spring 2025 Edition

Because Mondays need a little extra sparkle, here are some Black art exhibitions lighting up the world right now:

The Time Is Always Now: Artists Reframe the Black Figure (March 8–June 29, North Carolina Museum of Art): 23 artists celebrating the richness, joy, and beauty of Black life-think Kerry James Marshall, Amy Sherald, and more.

Faith Ringgold’s “Tar Beach” (May 9–Sept 7, Guggenheim): A quilt, a rooftop, and a young Black girl claiming her freedom. Iconic, inspiring, and pure joy.

Adam Pendleton: Love, Queen (April 4, 2025–Jan 3, 2027, Hirshhorn): Text, abstraction, and Black resistance in every brushstroke.

Kandis Williams at Walker Art Center (April 24–Aug 24): Collage, sculpture, and a whole lot of creative energy.

Raymond Saunders Retrospective (March 22–July 13, Carnegie Museum of Art): Layered, enigmatic, and full of surprises.

Art is how we remember, resist, and rejoice. So this Monday, let’s carry our history with a little more laughter, a lot more color, and maybe even a dance break.

Happy Monday, Hope it’s a good one.

Until next time,

Marley

Gorgeous treatment of turning historical grief into resilience. It’s my experience too. Charlotte Sheedy