In Search of a Black Hole Sun

On alt-Black girlhood, moshing as ritual, and the sound that raised me.

Like what you’ve been reading? THIRD SPACE is built on memory, resistance, and rhythm—and your support keeps the door open. Becoming a paid subscriber means investing in independent Black storytelling, and in the soft power of voices like mine.

Join the space. Stay for the stories. Let’s build an archive.

Wake-Up Songs & Sonic Portals

This isn’t a story about Soundgarden. It’s about what happens when a Black girl hears herself in distortion, and decides to stay.

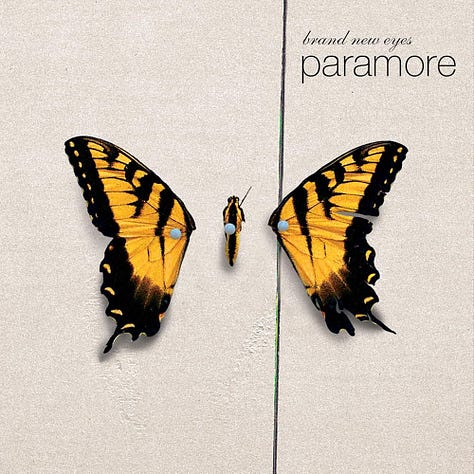

Every morning, the opening chords of Soundgarden’s “Black Hole Sun” rip through the dawn quiet as my alarm. It’s a ritual I’ve kept since freshman year of high school, when my best friend Omayah first slipped this 90s grunge relic into my playlist. I still remember that initial listen: the song’s warped guitar melody and haunting chorus felt like stepping through a portal.

Chris Cornell’s voice was ethereal and dreamy, floating above the distortion In my half-asleep state, those echoing “Black hole sun, won’t you come?” refrains sounded like a summons from another world. The surreal pull of the song—its sleepy, psychedelic tone beneath a layer of crunchy guitars—made reality feel pliable. It was as if the music itself were a cosmic doorway opening up just for us two alt-Black kids, calling us to an audio dimension where we finally fit.

Omayah and I clung to “Black Hole Sun” like a secret, sacred alarm clock. For a Black girl who grew up on her parents’ Anita Baker and Cameo records, embracing a grunge anthem felt almost transgressive. This was music many would say was “never meant for you.”

Indeed, outside our little row of lockers, few people who looked like us seemed to be Soundgarden fans. I’d been conditioned to think rock belonged to white kids—an assumption reinforced every time someone labeled me an “Oreo” for my taste in music (Black on the outside, “white” on the inside). But each morning, that song’s otherworldly soundscape reminded me that there was a place—even if an imaginary, sonic one—where a Black alternative girl could belong without question. In my mind, “Black Hole Sun” became more than a song; it became a symbolic space, a private universe born from distortion and dream, where I could be both different and home.

What does it mean to find yourself in music that wasn’t “meant” for you? I began asking myself this as the song warped my wooden attic room into a galaxy of its own. The question haunted me in the best way. Part of the answer lay in the music’s openness: Cornell’s lyrics were famously impressionistic and not tied to a single meaning. That meant I could pour my meaning into them. He even said the title “Black Hole Sun” came from a misheard news report and that the song is “kind of asking for hope… grasping for some kind of hope out of depression,” without any specific narrative—a blank canvas of feeling.

To an 14-year-old Black girl quietly battling her own storms of self-doubt, those fuzzy, comfortably-unreal sounds and melancholic lyrics were oddly healing. It felt like the song understood loneliness and longing—themes I wasn’t supposed to admit I felt.

In many ways, finding refuge in rock music felt like slipping into a hidden THIRD SPACE. I was living in a world that didn’t expect a Black girl to headbang to grunge, yet here I was—inhabiting a personal wormhole where that music spoke to my soul. I think of artist Robert Pruitt’s drawings of Black figures floating in cosmic settings for a visual parallel.

In Sarcophagus (2019), for instance, Pruitt depicts a Black woman “in transition, headed to another realm…anywhere but here.” She is enveloped in a sea of gold, with only her face and feet visible—floating, fragmented, sovereign. Pruitt gives us the architecture of becoming: a Black figure suspended between worlds, claiming a new space in the void. In the same way, I floated between musical worlds each morning, fragmented by the contrasts in my identity yet sovereign in the little universe carved out by that song.

To anyone else, it’s just a moody rock ballad from 1994. But to us, “Black Hole Sun” was a sonic portal. Its swirling guitars and eerie harmonies were a vortex that sucked us in and shielded us from the expectations outside. We’d sit on the ledge outside our cafeteria (we were lame so we didn’t have a place to sit), eyes closed, letting the waves of sound wash over us like we were being cleansed.

In that liminal state between sleep and waking, I felt seen by unseen forces. That song became a question and an answer at once: Could a Black girl find herself in music that wasn’t made with Black girls in mind? The answer, echoing each dawn, was yes. In the privacy of those stolen moments, yes. We could belong in any music that spoke to us. We could create meaning where the world told us we didn’t exist. It was our little rebellion: each day we woke not to an R&B chorus or a gospel hymn, but to a grunge hymn about a black hole sun. We turned a rock song into a refuge—into ours.

Paramore Made Me Cry (and Scream)

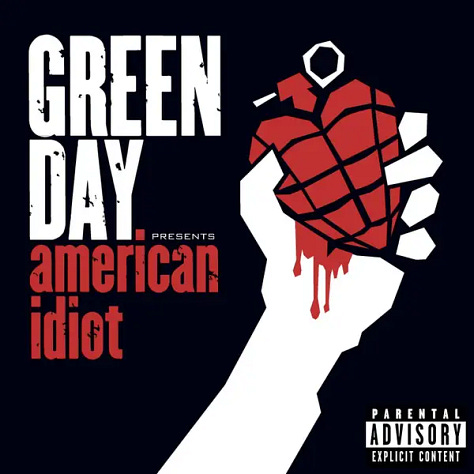

If Soundgarden opened a portal, Paramore built me a home there. The walls of that home were plastered with angsty lyrics and powered by Hayley Williams’ electric voice. My middle school and high school years had an emotional soundtrack composed largely of Paramore’s discography—songs that made me cry, scream, and feel alive all at once. I’d slam the bedroom door and blast “The Only Exception” on the hardest days, Hayley’s gentle verses about hesitant love coaxing out tears I’d learned to hide.

Other times, when sadness morphed into frustration, I’d howl along to the soaring bridge of “All I Wanted”—that famous high note (“All I wanted was yoooou!”) releasing something primal in me. And on days when I needed resilience, I’d dance in front of the mirror to the steel-drum bounce of “Hard Times”, a grin on my face even as the lyrics acknowledged “we’re gonna get rocked to the core.” This band was the blueprint for embracing my own interiority: they taught me that a girl could shout about her sadness and still come out powerful on the other side.

Seeing Hayley Williams pour her whole soul into songs—sometimes with a raspy scream, sometimes with a delicate whisper—was revelatory. Here was a young woman feeling unabashedly. Williams showed that vulnerability and strength could exist together. That range gave me permission to explore my own range of feelings.

I’d often felt pressure to perform strength, to be “strong Black woman” and shake off pain with no complaint. But singing along to Paramore, I could be fragile, heartsick, unsure and it didn’t make me weak. If anything, it made me feel powerful in a new way. Those bedroom sing-alongs were like therapy sessions. I was a quiet kid, the one who never wanted to burden my parents with teen drama. Yet I could stand in front of my mirror, eyes closed and fists clenched, belting “I never promised you a happy ending, you never said you wouldn’t make me cry” (a misremembered mash of Paramore lyrics and my own feelings) and allow myself to hurt out loud. Paramore normalized that emotional exorcism. Hayley’s very example said: you can hurt and still be heard. You can be soft and still command a room (or an arena full of fans).

In the halls of my predominantly Black high school, though, I often felt like an alien for loving this music. At school dances or pep rallies, the DJs stuck to hip-hop and Jersey club.

Paramore became my secret solace. I’d scribble their lyrics in my notebook margins in looping cursive, careful not to let nosy desk neighbors see. I lived a double life: bumping whatever was popular on the bus ride home to fit in, then racing to my room to crank up Riot! or Brand New Eyes once I was safe behind closed doors. I didn’t know more than two other Black girls who loved emo-pop the way I did. It was easy to believe I was just weird, an anomaly.

Yet the irony is that so many Black girls of my generation were doing the exact same thing in secret. We now know, thanks to the internet, that we were never truly alone. In fact, a joke tweet stating “Black people love Paramore” went viral, garnering thousands of retweets and even a delighted response from Hayley Williams herself—clearly, a lot of us had been out there vibing to “Misery Business” and “crushcrushcrush” on the low!

One Black Paramore fan described her shock at the tweet’s popularity: “I really thought I was alone!” she said, realizing so many others shared the same love. That recognition was validating. It’s like we all had permission to come out of hiding and bond over the music that saved us. Suddenly the thing that isolated me became a thing that connected me to my community—a community we didn’t even know we had.

Why did Paramore resonate with so many Black girls? Partly, I think, because their music forged a path to emotional honesty that we desperately needed. There’s a raw emo sensibility, a wear-your-heart-on-sleeve ethos, in songs like “The Only Exception” or “Fake Happy.” That sensibility clicks with the reality of Black girl survival in a world that often expects our strength but not our pain. As rapper Princess Nokia (herself an Afro-Latina who grew up on emo) once explained,

“There’s a vulnerability in associating with pain and sadness that has always lived in [this music’s] narration. For example, the blues—Black people have always loved the blues; they basically created the blues. Black people created rock music…it’s a fact… Black people created punk…the band Death was way before The Ramones… This is our shit. Naturally, that’s why we return to it. It’s ours.”

Her point hits home: the feelings that emo music openly wrestles with—heartache, depression, longing—have been coursing through Black musical traditions for centuries. The blues, spirituals, R&B ballads—they were all about voicing pain and finding power in it. Emo and pop-punk, for all their “white suburban” packaging, carry some of that same DNA. Maybe that’s why singing “that’s what you get when you let your heart win!” at the top of my lungs felt so cathartic and familiar. On a gut level, it was as soulful as any gospel choir number.

And Paramore, in particular, had a few secret ingredients that drew Black girls in. Hayley Williams sang with a churchy passion at times, and the band wasn’t afraid to get a little funky (their hit “Ain’t It Fun” even features a gospel-style choir in the bridge). Plus, Hayley’s vibrant hair and punk fashion aside, she could really sing—and we Black folks love a vocalist who can saaang. She had range (as any of us who’ve attempted that final chorus of “All I Wanted” can attest). In a way, Paramore bridged worlds for us: rock enough to vent our teen angst, soulful enough to feel like home.

Of course, Paramore wasn’t my only outlet. I headbanged to Evanescence in middle school, entranced by Amy Lee’s gothic drama; I pogoed in my bedroom to Avril Lavigne’s pop-punk anthems, pink-streaked hair and neckties on my mind. I screamed along to My Chemical Romance and Linkin Park when I needed to feel understood in anger. Many of us sampled that whole smorgasbord of 2000s alt-rock.

But Paramore remained at the center of my emotional soundtrack because they offered the clearest mirror to my inner life. Through their music, I learned that spilling my feelings wasn’t a liability—it was a superpower. Every tearful sing-along and joyous bedroom mosh was a small act of survival, a way to feel and keep going. If the first step to healing is admitting you’re hurt, then belting out “God, it just feels so…**(so) far from real”* (from “All I Wanted”) was my way of doing just that. Paramore made me feel seen from the inside out.

Today, I smile at how things have changed. The culture is catching up to what we knew all along: Black girls can moshed in Vans sneakers and studded belts just as much as we can twerk or sing gospel. There’s even a podcast cheekily titled “Black People Love Paramore”, dedicated to Black folks’ seemingly unexpected cultural faves. The secret’s out, and it’s glorious. It turns out we always belonged in this music—it was ours from the start, waiting for us to claim it.

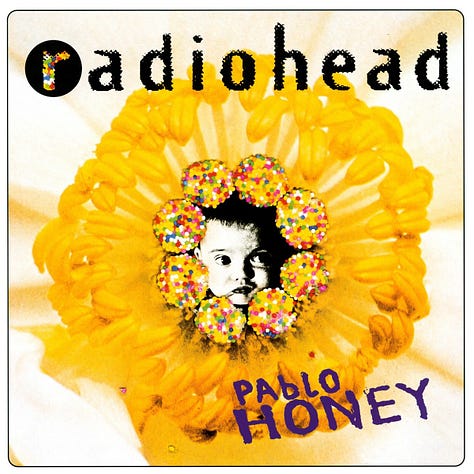

Mosh Pit Baptisms & Space Cowboys

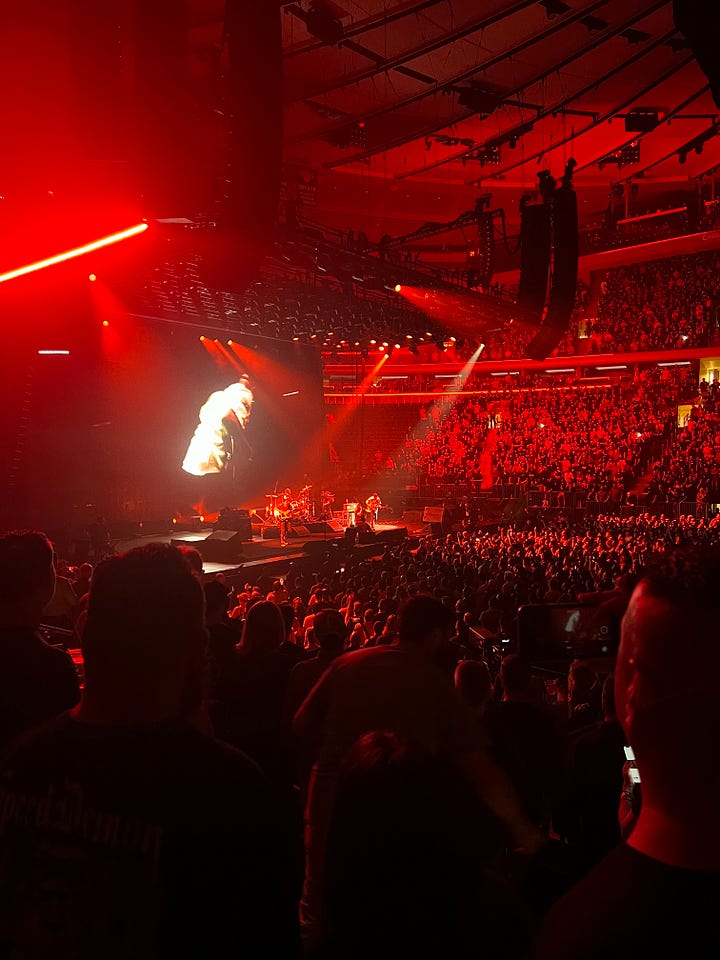

If Paramore gave me the language of feeling, Rage gave me the ritual of release. The first time I threw myself into a mosh pit, it felt like a baptism. The setting: a Rage Against the Machine reunion tour, with Killer Mike (of Run The Jewels) opening the show. I was 17, exhilarated and a little terrified, standing on the floor of a massive arena among a sea of mostly white rock fans.

When Rage Against the Machine launched into their first song, the floor erupted. A tidal wave of bodies surged forward and suddenly I was in it—really in it—a swirl of sweat, denim, leather, and energy. For a split second, the sensible voice in my head squealed, What are you doing? But then adrenaline and music took over.

I jumped, shoved, yelled lyrics at the top of my lungs. The mosh pit was pure chaos, but it wasn’t hostile. It was communion. Strangers tossed themselves around with wild abandon, yet if someone slipped and fell (I did, at one point), multiple hands instantly hoisted them back up.

In that frenzy of flailing arms and Doc Martens stomping the concrete, I felt an intense camaraderie. It was as if we were all part of some unspoken ritual, where the price of admission was letting go of your fear. Each time the crowd heaved in unison to a brutal Zack de la Rocha scream, I felt a layer of my self-consciousness peel off. I was baptized in noise. I was finding belonging in the chaos.

Full post releases for free subscribers at 8:00 AM 07/17 EST!

Up on stage, Killer Mike had delivered a blistering set right before this—a Black man spitting politically charged rhymes to a rabid rock audience, seamlessly bridging hip-hop and punk attitude.

Watching him earlier, I felt a revelation spark: my Blackness doesn’t oppose rock; it powers it. Here was living proof. Killer Mike’s mere presence, his voice booming about social justice over El-P’s distorted beats, had the crowd in his palm. The synergy was undeniable. It drove home something that should have been obvious: Black energy has been in rock and punk all along. Punk rock’s rebel spirit owes a debt to Black pioneers too (the all-Black punk band Death was shredding in Detroit before the Ramones ever formed, and DC’s Bad Brains defined hardcore punk in the 1980s).

Standing in that mosh pit, I felt this truth in my bones. The defiant fury of punk, the catharsis of communal rebellion—that has always echoed the spirit of Black resistance and resilience. No wonder it resonated with me so deeply.

As the guitars squealed and I screamed along—“F*ck you, I won’t do what you tell me!”—I realized I was part of the continuum that artists like Princess Nokia and Rico Nasty talk about: reclaiming rock’s legacy for those of us who were written out of its history.

I thought about the Afropunk movement, a now staple of summertime, a festival and community built by Black punks who were tired of being invisible in the scene. Now I understood their drive viscerally. In that moment, sweat-drenched and ecstatic in the pit, I embodied the idea that our presence isn’t an aberration– it’s essential. My very being there was powered by the same rebellious fire that fuels punk music.

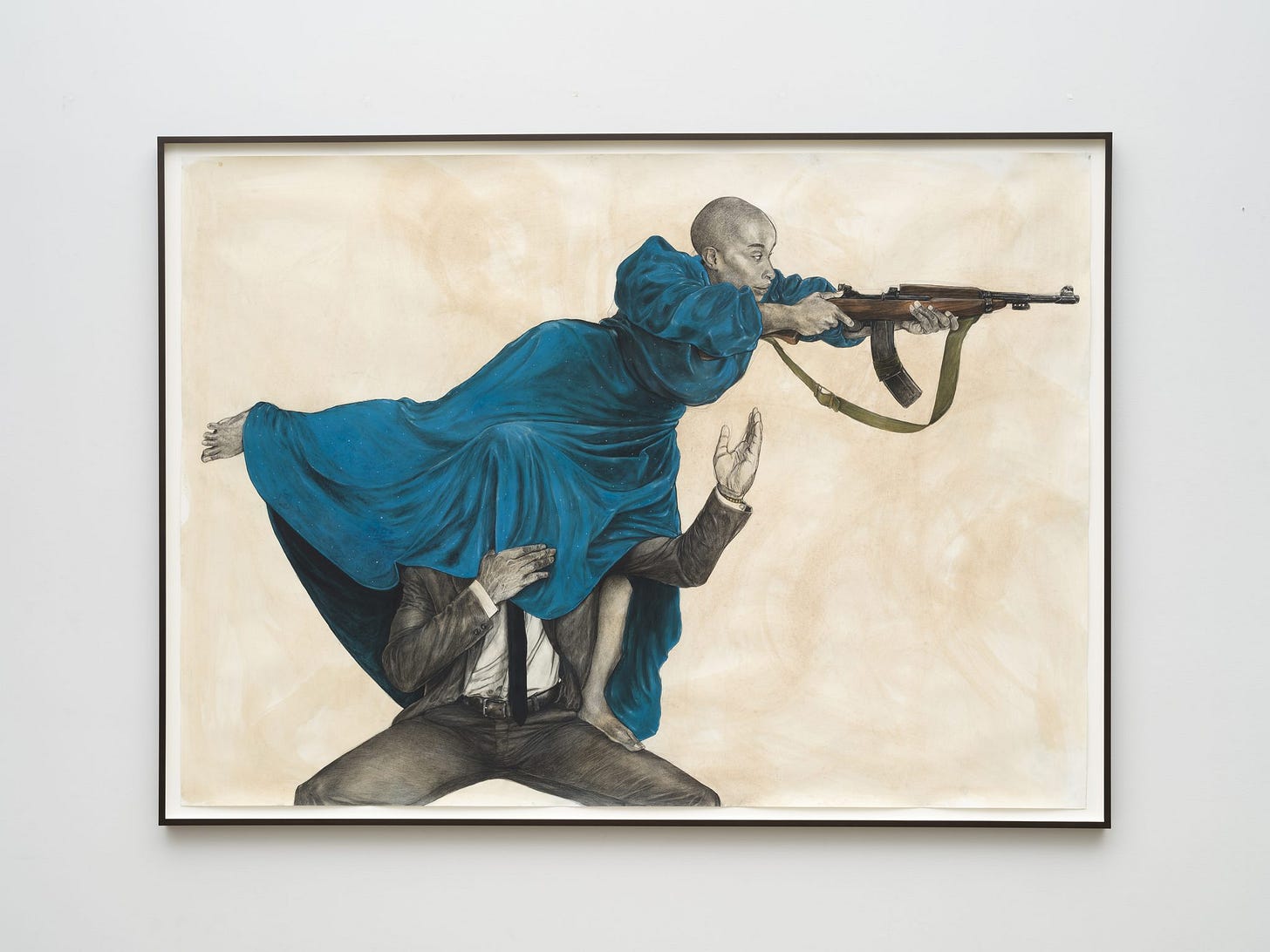

There was an almost spiritual symmetry to it all. In Robert Pruitt’s This my new dance move, I just don’t know what to call it (2022), a Black couple is locked in an intense, almost absurd dance. The man’s head is shrouded by a flowing blue dress, crouched into a human platform as the woman strikes a militant arabesque above him. Her pose is part battle cry, part balle. Elegant yet forceful.

Pruitt infuses humor into the composition, but there’s a deeper commentary at play: the man’s hidden face hints at new models of Black masculinity, while his posture physically supports the woman’s ascent. The result is choreography as rebellion—bodies interlocked in a pose that makes play look radical and makes power look collaborative. I thought of this piece as I pushed through the mosh pit. My movements, like hers, were absurd and sacred. A riot of limbs, a reverie of rhythm.

The ethos I carry from those experiences—from singing emo ballads in solitude to surviving a mosh pit sacrament—is one of joyful irreverence and rebellion. I’ve embraced being the space cowboy of my own story: a little weird, a little wild, and completely unwilling to let anyone box in my identity.

Joy, irreverence, rebellion—these are the pillars of my alt-Black girl creed. Joy in finding music that lights up my soul, no matter the genre. Irreverence for the expectations I’ve gladly defied (who says a Black girl can’t crowd-surf at a punk show on Friday and sing gospel at church on Sunday?). And rebellion in carving out a space for myself in scenes where we’ve historically been sidelined. I carry that rebellion gently, sometimes without even saying a word – in the band t-shirts I rock under my blazer at work, in the Paramore lyrics tattooed on my ribcage, in the way I blast both Megan Thee Stallion and My Chemical Romance with the windows down, defying anyone’s narrow idea of Blackness.

Before I close this out, I keep thinking of another Robert Pruitt piece that lives in my head like a visual echo of those long, liminal nights. In I Turned Myself into Myself (2018), a young Black woman reclines on a couch, half-swaddled in winding sheets that flow around her like a cocoon.

Only her head, one foot, and one hand are free—and in that free hand, she’s holding a comic book. The pages show Marvel’s Silver Surfer being commanded to rise by his creator Galactus. Above her, clipped to her hair like a crown, is a small reading lamp casting eerie blue light. Her expression is private, radiant, like she’s heard something divine just outside the frame. Pruitt transforms a simple moment of late-night reading into a full metamorphosis. The couch becomes a chrysalis, the comic a text of transformation. That piece makes me think of all the nights I stayed up with headphones on, letting songs like "All I Wanted" or "Black Hole Sun" wrap around me until I felt something shift. Like Pruitt’s girl, I too have turned myself into myself—through rhythm, through grief, through dream.

“What does it mean to find yourself in music that was never meant for you?” I posed that question as a shy freshman; I live the answer now. It means redefining the concept of “meant for you.” It means realizing that no one can decide what feeds your spirit except you. Music doesn’t have to look like you to belong to you.

Sometimes you have to step into the portal, claim the song, the scene, the sun, and make it yours. I found myself in so-called white music and discovered it had been part of me—part of —all along. As Paramore’s Hayley Williams once sang in a hushed tone,

I’d never sing of love if it does not exist.

Well, I’d say the love we alt-Black girls have for these songs does exist—fiercely, defiantly, beautifully so.

In the end, I didn’t just find a Black Hole Sun; I built a whole cosmos around it. A personal THIRD SPACE where Soundgarden can be a morning prayer, where a Black girl screaming along to “Misery Business” is a warrior finding her battle cry, where a mosh pit is as sacred as a church pew.

In this space, we become exactly who we’re meant to be: the dreamers and the dreamed-of, the girls who yell and laugh and rage and shine. In the words of Sun Ra (one of Afrofuturism’s patron saints), “space is the place.”

We create new worlds for ourselves. I am becoming the dream my younger self whispered about when she felt like a misfit. And I know there are others like me, becoming their own wild, loud, transcendent dreams. Together, we’ve stepped through the sonic portal and claimed our rightful place under the Black Hole Sun—a place we always belonged, a place we finally call home.

Until next time,

Marley

If this piece made you feel seen, strange, or sovereign, consider subscribing to Third Space or buying me a coffee so I can keep making work like this. This is a labor of love and lineage, but also… time. Tuition. Lattes. Licensing.

→ Subscribe: marleyedias.substack.com

→ Tip jar: coff.ee/marleyd

Thank you for being here. For reading. For listening. For becoming.