NEW MASTERS, OLD GHOSTS

Kerry James Marshall’s Souvenir I, the Civil Rights afterlife, and the burden of telling Black stories out loud.

As of this week, there are 724 of you subscribed to THIRD SPACE. That number still startles me—in the best way. Thank you for reading, for sharing, for caring about Black art enough to meet me here. That kind of quiet support is its own form of witnessing. It reminds me that this work—this memory work, this labor of care—is seen. And that makes all the difference.

As the curator of a growing Black art-focused page, I often feel the pressure that comes with increased visibility. With each post, I shoulder the emotional and intellectual labor of telling Black stories in public, aware that thousands of eyes—supporters and skeptics alike—are scrutinizing every word.

Standing before Kerry James Marshall’s monumental painting Souvenir I, I feel that weight reflected back at me. The artwork is a lush, reflective shrine to Black memory and mourning, and it resonates with the very mission that drives my work.

In this installment of THIRD SPACE, I examine how Marshall positions himself both within and against the Western canon’s old masters, even as I navigate forging my own path to mastery as a Black cultural voice today. Souvenir I becomes our meeting point—a place where the legacies of the 1960s Civil Rights era converge with the present challenges, and where art and personal advocacy illuminate one another.

A Souvenir of Loss and Resilience

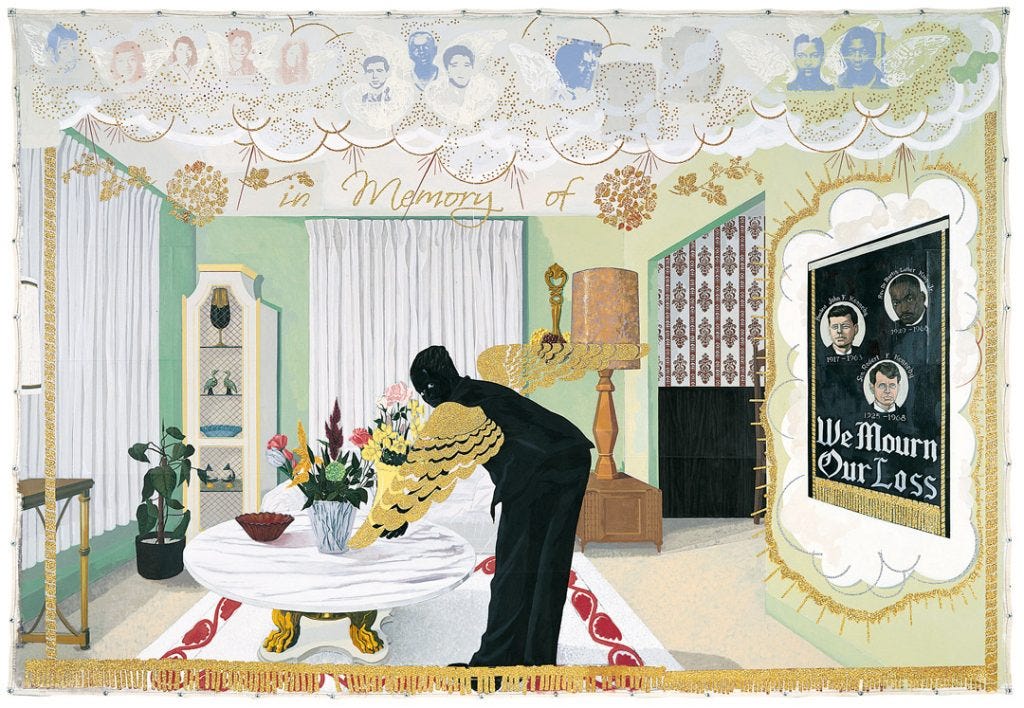

Souvenir I (1997) by Kerry James Marshall, acrylic, collage, and glitter on unstretched canvas, 108 x 157. In this towering canvas, a Black woman with golden, angelic wings bends over a table of bright flowers in what appears to be a middle-class living room.

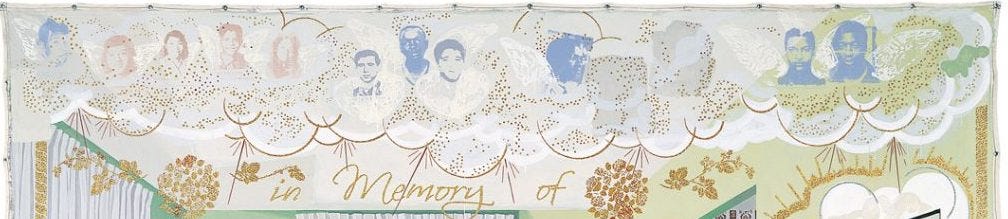

Above her, a white cloud stretches across the top of the composition, inscribed with the words “In Memory Of” in shimmering script. Within the cloud float the faces of martyrs of the 1950s–60s Civil Rights Movement – figures like Medgar Evers, the four girls killed in the 1963 Birmingham church bombing, and Malcolm X – each adorned with delicate wings “like cherubim… from Baroque painting.”

To the right, a black banner or plaque trimmed in gold bears the mournful words “We Mourn Our Loss” alongside portraits of leaders including Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., President John F. Kennedy, and Senator Robert F. Kennedy, with their birth and death dates.

Marshall has, in effect, transformed a domestic interior into a sacred memorial space. The painting brims with glittering ornamentation – swirls of gold glitter, pearlescent halos, tasseled trim – giving it the aura of a religious tapestry or a funeral banner.

Indeed, Souvenir I is executed on an unstretched canvas hung by grommets, much like a processional banner, and its use of glitter and tassels deliberately evokes the look of commemorative cards and even the regalia of the Catholic Church. The effect is both fantastical and reverent: a living room becomes a chapel of memory.

At first glance, Marshall’s imagery might even seem sentimental – the kind of nostalgic, mass-produced memorial poster one might have found in a Black home in 1968. In fact, the artist was directly inspired by the commercial souvenirs that flooded the market after King’s assassination.

But Marshall takes that kitsch sentimentality and develops it into something far more significant. The canvas is rich with art-historical cues: the golden wings and cloud of cherubs nod to European old masters’ religious paintings, while the large scale and somber subject matter align with the grand tradition of history painting (the most “elevated” genre in academic art). By interweaving these elements with Black iconography and personal memory, Marshall elevates the collective grief of Black America to the level of epic narrative. Souvenir I is at once a tender domestic scene and a monumental history painting; it merges private grief with public commemoration.

The wallpaper, furniture, and quiet act of arranging flowers speak to everyday life, even as the heavens above literally glitter with the names and faces of Black heroes and innocent souls lost. In this way, Marshall honors those lives on a heroic scale, asserting that their stories deserve to be preserved in our cultural memory just as zealously as any triumph in a textbook. The painting stands as a proclamation that the trauma and sacrifices of the civil rights era are not only his generation’s personal sorrow, but also an integral part of the American story.

Old Masters, New Masters

Marshall has long understood that challenging the art-historical canon requires a dialogue with it. He once observed, “I had to recognize that in that pantheon of Old Masters, there are no ‘Black Old Masters.’” This stark truth became a driving force in his career.

To rectify that absence, Marshall set out to insert Black figures and perspectives into the highest echelons of art – and to do so on his own terms, he knew he must achieve a level of skill comparable to the revered painters of old. His ambition has always been to attain an expertise and proficiency to match the Old Masters whose works hang on museum walls.

In other words, his paintings needed to “pass muster alongside the revered classics that make up the canon” – because that, as one critic put it, was the only way to truly contest the canon, to rewrite the master narrative of Western art history from the inside. Marshall’s strategy wasn’t mere mimicry of Renaissance or Baroque styles; he wasn’t interested in pastiche. “I’m not trying to paint in the same style [as the Old Masters],” he explained, “but to do the equivalent nowadays; to apply the same kind of logic.”

In practice, this meant mastering classical techniques and conventions – mastering painting itself – and then retooling them to center Black subjects. He adopts motifs like idealized poses and lavish decorative flourishes “like something from Fragonard” as a way of signaling his erudition and authority, even as he fills those motifs with content the old European masters never dreamed of. In essence, Marshall positions himself both within and against the Western canon: fluent in its visual language, yet resolutely telling stories that the canon historically ignored. His work hangs in the same halls as that of Rubens or Rembrandt, but it proclaims a narrative those artists never told – the beauty, tragedy, and dignity of Black life.

This consciousness of legacy is even embedded in Marshall’s career milestones. The major retrospective of his work that toured U.S. museums in 2016 was tellingly titled Mastry – a play on “mastery” that underscored how confidently Marshall had claimed his place among the masters. Marshall, in effect, became a new master: not a passive inheritor of tradition, but an active rewriter of it. He proved that a Black artist could engage the lofty genres of Western painting and reinvent them, enshrining Black experiences on the grand stage that art history had so long denied.

Watching Marshall do this has been deeply instructive for those of us navigating cultural fields where Black voices were previously marginalized. While I am not a painter, I recognize a parallel impulse in my own work as a Black art writer and curator on a digital platform. I, too, have felt the need to learn the “old school” rules in order to bend them.

Running a popular art page on social media might seem a world apart from oil painting, yet I’ve found that to build credibility I must demonstrate a command of both mainstream art discourse and Black historical knowledge – a kind of dual expertise. In a sense, I’m forging a path to mastery as a Black cultural voice, studying the scholarship and criticism that came before me (my own kind of Old Masters) while also challenging their blind spots and biases.

Just as Marshall deliberately painted Black figures into the canon, I’m working to write Black artists into the conversation, ensuring they’re no longer footnotes but central to the narrative. It’s a delicate balancing act: honoring time-tested wisdom but also staking new ground. And like Marshall, I’ve learned that true innovation often means positioning oneself inside the establishment and against it at the same time – using the establishment’s language of mastery to say things that radically transform the story.

The Burden of Visibility

With greater recognition comes a heavier responsibility. When I first started THIRD SPACE, it was a labor of love with a small audience; now, as the follower count has swelled, so has the sense of duty to get it right.

I feel an obligation to represent each artist and historical figure with accuracy, respect, and depth. There’s a constant awareness that any post can educate – or misinform – thousands. This responsibility can be exhilarating, but it can also be nerve-wracking. I’ve found myself fact-checking a caption on Jean-Michel Basquiat or double-reading a quote by Zora Neale Hurston late into the night, because I know people rely on my content to learn about our culture.

In amplifying Black stories, I carry the awareness that I’m correcting omissions and misrepresentations that have persisted for decades. It is purposeful work, but it is also meticulous, careful work – the kind that doesn’t readily show in an Instagram thumbnail or a 280-character tweet.

There is an emotional weight to this work as well. Much of Black history and Black art is interwoven with trauma and perseverance. One week I might be writing about the jubilation of the Harlem Renaissance; the next, I’m highlighting artwork that responds to police violence or commemorates victims of lynching. Engaging with these histories day after day means I’m constantly processing grief, outrage, and hope, then translating those emotions into narratives for a broad audience.

It reminds me of the solemn, loving care with which the angel in Souvenir I tends to her bouquet – as if each flower were an offering to the fallen. Marshall painted that figure with a bowed posture and golden wings, a vision of both sorrow and transcendence. In my own small way, when I compile a post about, say, the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing (which killed four little girls in 1963), I feel a fraction of that sorrow and seek a form of transcendence through understanding.

Telling these stories in public is a form of mourning aloud and celebrating aloud. It takes emotional resilience to revisit painful chapters of history, and it takes intellectual rigor to present them honestly yet constructively. There are days when I finish writing about a tragedy and have to step away from the screen to collect myself. There are also days when the public nature of this work invites harsh pushback – trolls leaving racist comments, or well-meaning followers asking painfully uninformed questions that require patient correction. The visibility that helps spread knowledge also exposes the storyteller.

I’ve learned to develop a thicker skin and a more agile mind, responding to criticism without losing my core message. It is, as many Black creators and educators will attest, a unique burden to carry: to be seen as a representative voice, to pour heart and scholarship into every public utterance, knowing that any error or vulnerability is on display.

Yet, if Souvenir I teaches us anything, it’s that this labor of remembrance and representation is valuable work. Marshall’s painting suggests that preserving Black stories is itself a noble act, a way of honoring those who paved the way.

When I look at the care embedded in Souvenir I – the way a mundane living room was transformed into a hall of heroes – I’m reminded that what I do on a digital platform can also be a form of care. I’m curating a kind of living archive, a space where others can visit and feel the weight of Black history and the light of Black creativity. That realization turns what sometimes feels like pressure into a sense of purpose. Yes, it is a burden to carry so much history into the public sphere, but it is also an honor. It means the work matters.

Echoes of Two Eras

The trauma that Souvenir I enshrines is very specific: the collective grief of the late 1950s and 1960s, a time of both transformational progress and heartbreaking loss for Black America. To an earlier generation, the names written in Marshall’s clouds – Medgar Evers, Denise McNair, Addie Mae Collins, Carole Robertson, Cynthia Wesley, Malcolm X, Fred Hampton, and others – are not just names but wounds.

Each represents a life cut short and a community’s anguish. The Civil Rights era was an age of hope stoked by nonviolent resistance and legislative victories, but it was also an age of martyrdom. Leaders and innocents alike were beaten, bombed, and assassinated for the cause of Black freedom.

Marshall, born in 1955, came of age in the aftermath of these events; he was a child in Birmingham, Alabama, and later in Watts, Los Angeles, where the tumult of the era was impossible to ignore. He once reflected that with the killings of figures like Malcolm X in 1965 and then Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy in 1968, “it seemed like the end of America’s dream was near.”

This is the visceral historical context behind Souvenir I. The painting’s mournful grandeur—its invocation of angels and clouds to honor slain Civil Rights icons—captures the enormity of that era’s heartbreak. It invites those who didn’t live through the 1960s to imagine the emotional climate of those years: the dread, the defiance, the deep sorrow tempered by pride in the martyrs’ sacrifice.

Today, in the 2020s, we find ourselves again grappling with a moment of historic turbulence—one that, while very different in its specifics, carries some uncanny echoes of the 1960s. I have now lived through two Donald Trump presidencies, and it often feels like the traumas of a past era have been reawakened in our time. In the period spanning Trump’s first term in office and the tense years surrounding his attempt at a second, American society saw a surge of overt racism, division, and democratic backsliding that many of us never thought we’d witness in our lifetimes.

We watched neo-Nazis march with torches in Charlottesville in 2017, openly chanting white supremacist slogans. We saw a sitting president equivocate on condemning hate groups, giving them, in effect, a nod and a platform. We saw family separations at the border, a Muslim travel ban, and the disparagement of Black and brown nations in open rhetoric.

By 2020, as if in cruel symmetry with the unrest of 1968, we saw militarized police clash with peaceful protesters in the streets, clouds of tear gas on the evening news reminiscent of the fire hoses and police dogs of Birmingham. We even saw, in early 2021, an angry mob storm the U.S. Capitol – some carrying Confederate flags, an image that felt like a ghost from the 19th century resurrected in the 21st.

For many in my community, these events were deeply traumatic to live through. They shattered any illusion that the ugliness of America’s past was behind us. The sense of whiplash – that history was not a linear march toward progress but rather a pendulum swinging perilously – set in as we realized how fragile the gains of the Civil Rights movement could be. Living through the Trump era, especially the prospect of it repeating, has meant living with a constant undercurrent of anxiety and vigilance. It has meant mourning new losses and setbacks (from the lives lost to racist violence to the erosion of civil norms) even as we continue to fight for justice.

The parallels between the 1960s and today are not perfect, but they are instructive. In both eras, a struggle for Black dignity and equal rights was met with fierce backlash. In both, the nation was forced to confront the question of whose lives truly matter in our democracy. And in both, art and memorialization have played a crucial role in processing the pain.

Marshall’s Souvenir I was created in 1997, decades after the events it commemorates, yet it helped a generation to reflect and remember. Likewise, in our time, we’ve seen a proliferation of new memorials and artistic tributes: murals of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor on city walls, viral images of protest that themselves become symbols, poets and filmmakers grappling with the legacy of this era.

It’s as if every generation needs its own “souvenirs” of struggle and perseverance. My grandparents’ generation kept souvenir pamphlets of MLK’s speeches and wore buttons mourning JFK and RFK; today, we share images and hashtags, build digital archives of videos and testimonies, and create artworks that ensure the stories aren’t forgotten. The mediums have changed, but the motivation is the same: to remember, to honor, to learn, and to galvanize others.

Personally, living through this contemporary turbulence has lent a new urgency to my work on the art page. When I see Souvenir I’s glittering “In Memory Of” banner, I think about what and who I memorialize in my own posts. I think about how, during the summer of 2020, I dedicated a series of posts to artists who were creating work in response to police brutality—trying to shine a light on how creativity emerges from pain, much as Marshall’s painting did. I draw a direct line between the trauma Marshall depicts from the 1960s and the collective trauma my generation has endured.

The specifics differ—police shootings and political demagoguery versus assassinations and segregation—but the emotional register has parallels: the ache of loss, the anger at injustice, the determination to still envision a better future. Understanding that continuity has helped me find meaning in what might otherwise feel like endless bad news.

It’s a reminder that our ancestors went through fire and still found ways to make art, to organize, to push forward. If they could do it, so can we. The slogan “We Mourn Our Loss” in Marshall’s painting is written in beautiful, ornate script, as if part of a sacred hymn. It acknowledges pain without succumbing to despair. In my own life, I’ve tried to adopt a similar resolve: to acknowledge the setbacks and sorrows of the present, but also to underscore the resilience and creativity that keep bursting through, no matter what.

Toward a New Mastery

Reflecting on Souvenir I and my journey thus far, I’m struck by how art and storytelling serve as bridges across time. Kerry James Marshall’s glittering memorial on canvas reaches from his 1960s childhood to speak to our 2020s reality. It shows that even as times change, the act of remembering—and the labor of making sure those memories endure—remains a powerful form of resistance and healing. In my own way, curating and writing about Black art on a digital platform is a continuation of that tradition.

By remembering and by insisting on our visibility, we who tell these stories push back against erasure. We create a THIRD SPACE (to borrow the term) where the past and present, the personal and political, meet. It’s a space where a centuries-old oil painting technique can sit alongside an Instagram post, and both can carry the flame of Black history forward.

Marshall has shown that to change the world’s view, you sometimes have to master the world’s tools—be they paintbrushes or publishing platforms—and then repurpose those tools for your own people. He placed himself among the Old Masters by painting Black figures with a technical virtuosity and depth that could not be denied. In doing so, he didn’t just join the canon; he altered its course.

That inspires me whenever I doubt myself. It reminds me that becoming one of the “new masters” in our cultural landscape isn’t about imitating what has been done before, but about boldly claiming space and excellence for stories that have been left out.

For me, that means striving for a mastery of research, writing, and outreach, so that I can speak with both moral authority and factual authority about Black art. It means treating a social media caption with the same care and seriousness that an art historian treats a museum catalog essay.

It means valuing both scholarly rigor and accessibility, so that the message can resonate widely without losing its substance. If I can do that, if I can continue to grow in knowledge and craft, then maybe I am on my way to forging that “new master” status—not for ego’s sake, but to better serve the culture that raised me.

There is a moment I often think about when I recall Souvenir I. It’s not a moment in time, but a visual moment in the painting: the angelic figure’s face is painted in Marshall’s signature deep, inky black, with no individuating features, almost as if she could be any Black woman—a universal caretaker of memory. She leans over the flowers in a gesture of gentle devotion. Above her, the golden names and faces sparkle.

Whenever I feel overwhelmed by the weight of what I’m trying to do—those nights when the hate comments pile up, or the days when I’m just emotionally drained by the news—I conjure that image. I imagine that Black angel in Souvenir I silently encouraging me. Her wings tell me that our pain can be transformed into something transcendent, and her domestic setting tells me that the work begins at home, in our own communities and personal initiatives.

The journey of telling Black stories—whether on a canvas or on the internet—is not easy. It is often draining, sometimes dangerous, and almost always demanding. But it is essential.

Kerry James Marshall’s Souvenir I shows the grace that can emerge from not just bearing witness to history, but actively commemorating it. It challenges us to remember those who came before, and in doing so, it hands us a baton. I like to think that with every post I make, every article I write, I’m taking that baton and moving it a little further forward. Old masters may not have included us, but new masters are rising – in art, in writing, in every field – to ensure that Black experiences are seen and valued.

In the end, the story of Black art (and by extension, Black life in America) is one of perseverance and renewal. Each generation, like Marshall’s winged figure, carefully tends to the memories and dreams left by the last.

Each generation, in turn, adds its own chapter to the narrative.

I’m grateful to play a part in this continuum, and I carry the lessons of Souvenir I with me: that mourning can be a catalyst for creativity, that mastery is as much about purpose as technique, and that telling our own stories – in all their pain and glory – is how we claim our place in history.

Until next time,

Marley

I needed this line today, “It acknowledges pain without succumbing to despair. In my own life, I’ve tried to adopt a similar resolve: to acknowledge the setbacks and sorrows of the present, but also to underscore the resilience and creativity that keep bursting through, no matter what.”