THE COST OF COOL

On Do the Right Thing, THIRD SPACES, shade equity, and why Black communities are still fighting for air—literally and politically.

This piece took weeks of research, writing, and early-morning editing sessions—between work, life, and staying cool in this July heat. If you value THIRD SPACE and want to help sustain this longform, deeply reported, Black-centered writing, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Paid readers keep this platform alive. And they help me cover the software subscriptions, the archive fees, the midnight lattes, and the moments of doubt it takes to finish essays like this.

Free subscribers will always get love here—but paid folks make it possible for me to keep pushing toward the next one.

I remember the first time I watched Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing, on a sweltering July afternoon much like the one it depicts. The film opens declaring “Place – Brooklyn, New York. Time – Present. Weather – Hot as shit!”. From the first frames, the block in Bed-Stuy shimmers beneath a white-hot sun. Neighbors fan themselves on stoops; children frolic in the spray of a busted fire hydrant; the air itself seems to ripple. Lee saturates the screen in red-orange heat, a haze of rising temperatures meant to serve as both literal oppression and metaphorical pressure cooker.

This heat is social thermodynamics: the hotter it gets, the closer this community inches toward combustion. By day’s end, in the eerie glow of a summer night, that pressure erupts – a pizzeria burned, a life taken by police, and rage crackling like heat lightning.

On these Bed-Stuy blocks, everyday Black life unfolds in what cultural theorists call a “THIRD SPACE.” The stoops, corners, and street fronts are neither home nor work but something in between—communal sites of improvisational survival and confrontation. Here, on the margin of public and private, characters create what Bell Hooks famously described as a “site of resistance… a location of radical openness and possibility.”

We see Mother Sister eternally posted on her brownstone stoop, eyes on the street; Da Mayor wandering with gentle wisdom and a hint of whisky; Radio Raheem pounding the pavement to the rhythm of Public Enemy. We see the three old men – “Corner Men” like a Greek chorus – ensconced in the meager sanctuary of a sidewalk’s shadow, swapping barbs and truths. These are the whispering corners of the bazaar, the kind of THIRD SPACES where, as one definition goes, “the oppressed plot their liberation.” In Do the Right Thing, such corners literally speak: people holler across balconies, debate on stoops, and jostle on sidewalks. Space becomes dialogic – a call-and-response of bodies and voices improvised in real time.

Crucially, these in-between spaces are where different worlds collide. Sal’s Famous Pizzeria sits on a predominantly Black block as a site of uneasy inter-racial contact – part refuge (a place to eat, to cool off in front of a whirring fan) and part powder keg. The sidewalk before Sal’s becomes a stage where questions of respect, ownership, and belonging play out. Buggin’ Out agitates for representation on Sal’s wall of fame; local teens breakdance on cardboard in the street; a white tenant bicycles nervously through Black Brooklyn.

On a single block, the cultures and claims of Black, Italian, and Korean-American residents intersect in what Homi Bhabha and I might call the THIRD SPACE – a hybrid space “free (maybe only momentarily) of oppression,” where new identities and conflicts are negotiated. It is an arena of both creative community and confrontation. As the heat index rises, so do tempers, revealing the fault lines of race and power that run through that shared space. The tragedy that unfolds by night’s end – police killing Radio Raheem, the enraged community venting its fury on Sal’s – underscores how precarious even a tentative THIRD SPACE can be when the state’s violence intrudes. The block is a haven from the wider world and a tinderbox saturated in that world’s injustices.

Yet even in the film’s explosive climax, there is a sense that something sacred lived on that block. The morning after the riot, as ash settles like a second dawn, neighbors gather on the same street where they brawled hours before. The block, battered but unbowed, remains a living, communal organism. Lee ends with two contrasting quotes—one from Martin Luther King Jr. urging nonviolence, one from Malcolm X asserting the right of self-defense—framing the burning question: What is the right thing?

"Violence as a way of achieving racial justice is both impractical and immoral. It is impractical because it is a descending spiral ending in destruction for all. The old law of an eye for an eye leaves everybody blind. It is immoral because it seeks to humiliate the opponent rather than win his understanding; it seeks to annihilate rather than to convert. Violence is immoral because it thrives on hatred rather than love. It destroys community and makes brotherhood impossible. It leaves society in monologue rather than dialogue. Violence ends by destroying itself. It creates bitterness in the survivors and brutality in the destroyers."--Martin Luther King, Jr.

"I think there are plenty of good people in America, but there are also plenty of bad people in America and the bad ones are the ones who seem to have all the power and be in these positions to block things that you and I need. Because this is the situation, you and I have to preserve the right to do what is necessary to bring an end to that situation, and it doesn't mean that I advocate violence, but at the same time I am not against using violence in self-defense. I don't even call it violence when it's self- defense, I call it intelligence."--Malcolm X

The film offers no easy answer, but it makes one thing clear: the streets themselves are speaking, bearing witness to both the heat of oppression and community resilience. The stoop, the corner, the hydrant spraying cool relief—these humble public spaces are where Black survival has long been improvised and where the possibility of justice flickers, even briefly, like a mirage in the summer air.

The Right to Loiter: Black Bodies, Policed Space, and Wayward Freedom

On that Bed-Stuy block and far beyond it, simply occupying public space while Black has historically been an act fraught with risk and rebellion. There is a direct line from Do the Right Thing’s depiction of a Black community claiming the block (for joy, protest, and just living) to a long tradition of Black spatial practice under constraint. Cultural historian Saidiya Hartman reminds us that at the turn of the 20th century, young Black women in cities like New York and Philadelphia seized moments of wayward freedom by “running the streets” – a refusal to be confined to white folks’ kitchens or circumscribed servant roles. These women strolled Harlem’s avenues in defiant style, “idling on corners and hanging out on front steps” in what Hartman calls “an assembly of the damned, the venturous, and the dangerous”.

In those streets, they crafted “a long poem of black hunger and striving,” their very presence a kind of insurgent choreography against the racial order. For their boldness in occupying space, they were often castigated as loafers or “trouble” – policed by vagrancy laws and moral reformers. One social worker sneered that a young Black woman in his charge had “enjoyed too much freedom… made her ungovernable”, deeming her liberty “a threat to public order.” To be young, Black, and aimless in public – to exist without a purpose deemed acceptable – was criminalized. Loitering, for Black folks, has long been coded as dangerous dissent.

Throughout American history, the Black body in public space has been surveilled and regulated – whether through formal laws (Jim Crow signs screaming “Whites Only” on park benches, segregation of pools and playgrounds) or through the unwritten rules enforced by stares and cell-phone 911 calls in our own time. Think of the cases that have gone viral in recent years: a white woman calls police on Black families barbecuing in an Oakland park, a neighbor questions a Black deliveryman for walking down a street in a gated community.

Invisible color lines have often carved up the American outdoors: the wrong neighborhood, the wrong time of day (consider “sundown towns” where Black travelers were menaced after dark), or simply the wrong demeanor can invite harassment. Even heat itself becomes racialized in these encounters – consider the common summer scene of Black kids joyfully opening a fire hydrant to cool off, only to face police crackdowns for misusing city water. Public space for Black people is always in tension between belonging and exclusion, visibility and vulnerability.

Urban architecture and design have too often abetted this inequity, shaping cities in ways that contain and control Black movement. In the mid-20th century, “urban renewal” projects slashed highways through thriving Black neighborhoods, creating physical barriers and social dead zones.

Today’s built environment still carries these legacies. Planners deploy “hostile architecture” – designs explicitly aimed at deterring those deemed undesirable – with chilling creativity. Benches are segmented with metal armrests (so no one can lie down), window sills spiked to prevent sitting, and public parks are fenced and surveilled so police can monitor whoever lingers. Even ostensibly neutral elements like landscaping are weaponized: sharp stones or thorny plants beneath storefronts to repel loiterers, bright floodlights that make gathering unpleasant. Such measures, by design, signal who is unwelcome.

Hostile design “privileges one user over another” and is often used “to restrict the use of a public space based on race, age, income and other factors deemed undesirable.” In other words, architecture can be a quiet accomplice to racial profiling – encoding segregation into concrete and metal. The result is a patchwork of partitioned urban spaces: cozy seating, shade, and leisure for some; hard edges, heat, and exposure for others.

And yet, against these strictures, Black communities continuously carve out sanctuaries of life in the open air. There is a reason the front stoop looms so large in Black cultural memory – from the brownstones of Bed-Stuy to the porches of the Black South. These semi-public, semi-private perches have long been sites of what scholar Sharon Sutton calls “improvisational spaces of resistance,” where neighbors bond and watch out for each other in defiance of inhospitable surroundings. Sociologist Elijah Anderson writes of the “cosmopolitan canopy,” those rare urban oases (like Philadelphia’s Reading Terminal or DC’s public markets) where a tentative civility allows diverse folks to commingle. But even where no formal canopy exists, Black people have created their own: a card table on the sidewalk for dominoes, a boom box and a dance circle at the corner, a church folding-chair revival under the trees of a city park. These are acts of claiming space – asserting that we belong in public, in joy as much as in protest. The margin can indeed become a place of “radical openness,” as bell hooks said.

Do the Right Thing’s Bed-Stuy block exemplifies this: despite the literal heat and the heat of racial conflict, it thrums with Black social life, self-regulation, and pride. The tragedy occurs when an outside force – police authority, carrying the historied violence of the state – crashes into that space and tries to snuff it out. But the morning after, the block is still there. The people are still there. The fight over who gets to occupy the block goes on.

We Real Cool (Gwendolyn Brooks, 1960)

We real cool. We

Left school. We

Lurk late. We

Strike straight. We

Sing sin. We

Thin gin. We

Jazz June. We

Die soon.

Fire This Time: Climate Crisis, Urban Heat Islands, and the New Jim Crow Thermometer

In 2025, the planet is hotter than ever, and nowhere feels more cruel than the neighborhoods Spike Lee put on the map. The fundamental question of who will suffer most from extreme heat is, as one writer put it, “bound to systemic issues of race and class.” Oppressive heat has long been a metaphor for oppression itself in Black art – from James Baldwin noting how Harlem’s asphalt soaked in the heat all day only to radiate misery all night, to Chance the Rapper’s rueful line “everybody dies in the summer / so pray to God for a little more spring.” But today, that metaphor is alarmingly literal. Climate change has cranked up the thermostat on our summers, and thanks to decades of racist housing and planning, Black and brown communities are disproportionately baking.

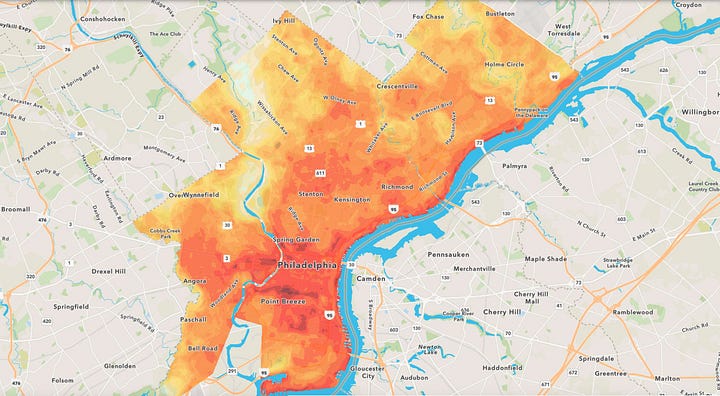

A groundbreaking study of 108 U.S. cities found that formerly redlined districts – the very areas where banks refused loans to Black families in the 20th century – are now on average 5°F hotter in summer than their non-redlined counterparts. In some cities, the gap is as high as 12°F or even 20°F. Stroll through Baltimore or Philadelphia on a blistering day: you can all but see the color line in the heat map. Leafy, park-blessed (and largely white) neighborhoods enjoy generous shade and cooler temps, while treeless blocks of row homes sizzle across the literal tracks.

This is the Urban Heat Island effect, turbo-charged by segregation’s legacy. Decades of disinvestment mean fewer trees and green spaces, more asphalt and dilapidated housing that traps heat. As one climate justice advocate put it, residents of these neighborhoods are “literally dying for a breath of fresh air.” – heat and air pollution now kill inner-city Americans at higher rates than almost any other cause. In New York City, data from 2011-2021 shows Black New Yorkers were more than twice as likely to die from heat exposure than whites. It’s not that the sun discriminates; it’s that our policies have ensured the harshest sun falls on those least protected.

Protection, indeed, is unequally distributed. Cool refuge in a heat wave comes from shade and air-conditioning, which reflects privilege. A 2019 investigation in Places Journal asked pointedly: “Who decides where the shade goes?” In Los Angeles, it turned out, bus shelters (critical sources of shade for transit-dependent people) were installed first in affluent areas where advertising revenue was highest. Poorer neighborhoods, predominantly non-white, were left to literally burn. Even attempts by community members to DIY their own shade – an awning here, a makeshift canopy there – run into bureaucratic roadblocks and codes that perversely prioritize “order” over life-saving relief. Meanwhile, many low-income households struggle with inadequate or nonexistent air conditioning; they face the devil’s bargain each summer day of risking heatstroke at home or braving the sun outside. These disparities are why experts talk about heat as not just a weather pattern but a justice issue. The question isn’t just “How hot will it get?” but “For whom, and with what consequences?”

As the planet warms, we effectively live inside the world of Do the Right Thing. That film’s “hottest day of the year” in the late 1980s now feels prophetic: we are clocking new “hottest days” year after year. The boiling Bronx street where Mookie and friends sought any sliver of shade foreshadowed what climate scientists now confirm – that the hottest parts of our cities are overwhelmingly the Black and brown parts. Those communities also face higher rates of the chronic conditions (like heart disease and asthma) that make heat more deadly.

When Radio Raheem – a big Black man with impossible dreams, unfazed by the heat in life but felled by the chokehold of a cop – died on screen, he became a timeless stand-in for real victims from Michael Griffith in the 1980s New York to George Floyd in 2020. Now, Radio Raheem is also a stand-in for those being slowly killed by environmental racism – people struggling to breathe through heat and smog, bodies bearing the brunt of a rigged system (to use a word from Lee’s montage) that treats some lives as more expendable. As geographer Ruth Wilson Gilmore famously defines it, racism is the “state-sanctioned or extralegal production of group-differentiated vulnerability to premature death.” Extreme heat, disproportionately endured, is just such a production of vulnerability. It’s a slow killer, as lethal as any chokehold.

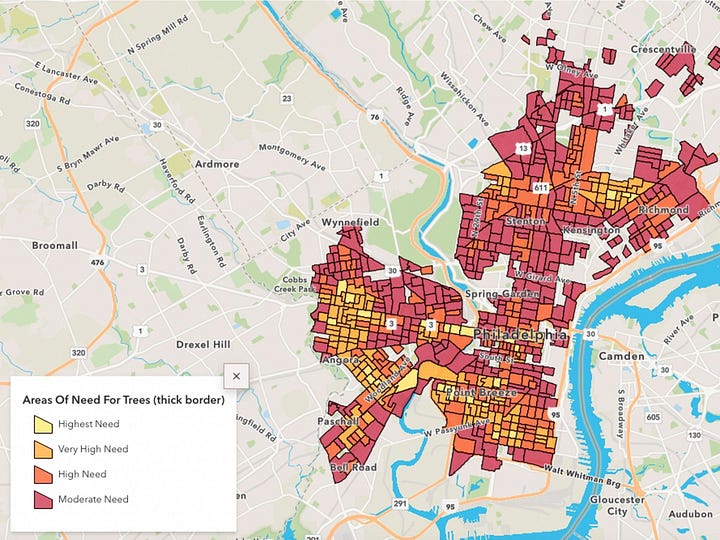

And still, there is nothing inevitable about this fate. The climate crisis forces us to confront not only carbon emissions but the spatial design of our cities. We have to ask why, for instance, wealthier (whiter) districts enjoy cooling green canopies and seaside breezes, while poorer (black/brown) districts languish amid heat-absorbing concrete and exhaust. We must question why public pools are closed or never built in the areas that most need them, and why cooling centers are underpublicized or inaccessible. We must interrogate why “sustainability” has become a buzzword for trendy green rooftops on luxury condos downtown, yet planting a hundred drought-resistant shade trees in an East Brooklyn public housing project is not headline news.

Spatial justice is climate justice. The fight for the right to safely occupy public space includes the fight for the literal right to live through a summer if you’re not rich. As one study co-author bluntly put it, the fact that redlined neighborhoods are scorching today “suggests a woefully negligent planning system” that benefited “hyper-privileged richer and whiter communities” while forsaking others. That negligence must end. If we do nothing, the current trajectory promises that “the same historically underserved neighborhoods… will face the greatest impact” from ever-hotter heat waves. In other words, if we don’t act, today’s urban heat islands will become urban sacrifice zones under the sun.

THIRD SPACE Futures: From Big Beautiful Bills to Cool Canopies

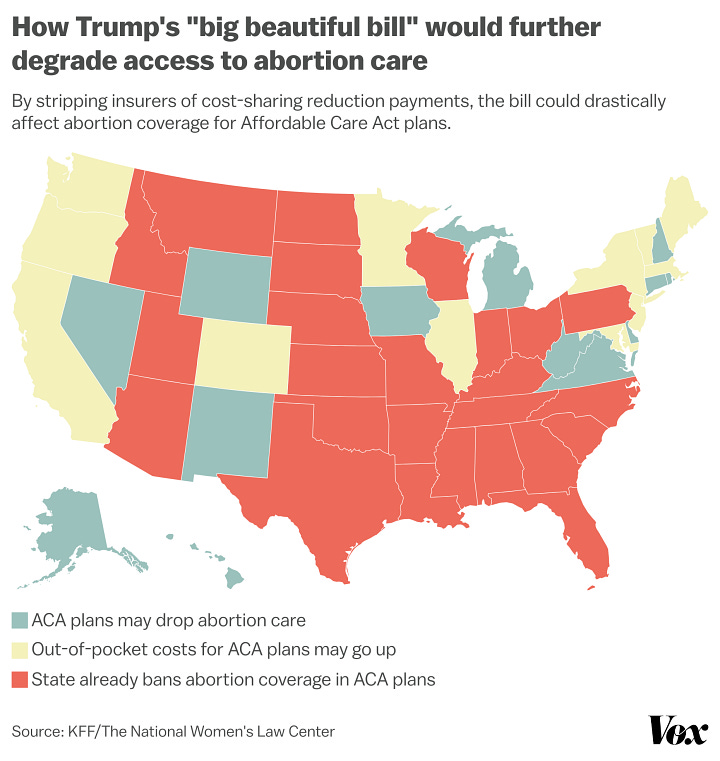

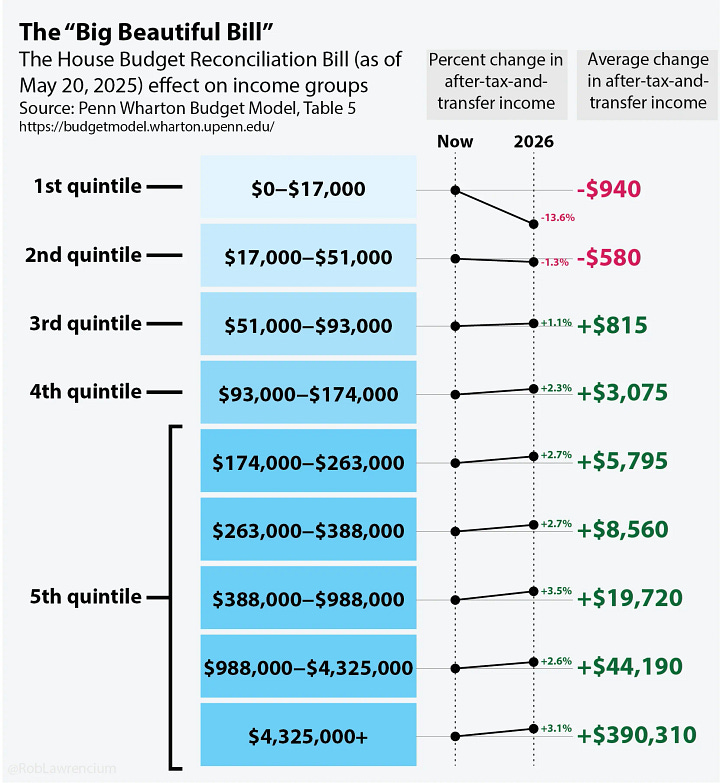

In the shadow of this crisis—and literally in search of shadows—we find ourselves here again, July pressing itself into our skin like a dare. Summer 2025. The air is thicker. The sun feels like it’s reaching closer. And somewhere on the Senate floor, lawmakers are debating the Big Beautiful Bill, a bloated, brutal piece of legislation stuffed with tax breaks for the rich, rollbacks on environmental protections, cuts to Medicaid and SNAP, and a proud little line item for “border fortification.”

They named it with the same swagger they used for the wall. Big. Beautiful. Like concrete and cruelty should be celebrated. Like enclosure is something we should aspire to. Like the dream is to build taller fences, hotter prisons, sharper divisions between who is inside and who is out.

This bill isn’t just about money. It’s a blueprint for who gets to live with dignity—and who gets left to swelter, starve, or suffocate. Cuts to climate programs in the middle of record-breaking heatwaves. Cuts to food assistance in neighborhoods already marked by red lines and food deserts. Cuts to Medicaid when Black elders are already dying at higher rates from heat stroke and respiratory failure. This isn’t a budget. It’s a weather forecast written in ink and indifference. It’s policy as arson.

And it feels like the natural next chapter of a government that spent years bragging about a wall like it was art.

That same logic of walls lives on in every zoning ordinance that denies public shade. Every cracked sidewalk without a tree. Every closed pool in a Black neighborhood. Every “No Loitering” sign is plastered on what should be communal space. The border may be far from Brooklyn, but the wall mentality lives here, too, shaping who gets to cool down and who gets to burn.

But even now, there’s another current. One that’s been rising since 2020. I remember it vividly—standing in my hometown of West Orange, New Jersey, holding a microphone with sweaty palms and a voice too full to stay inside. There were nearly 2,000 people there that day. Teenagers I grew up with. Elders with homemade signs. Kids on their parents’ shoulders. We stood in the sun for hours demanding what we shouldn’t have to demand: space, breath, survival, a say. I told our town leaders: “Give us space. Hear us out. And most importantly, listen.” I wasn’t just talking about seats at the policy table. I was talking about sidewalks. About park benches. About air.

That summer taught us that streets could be classrooms and churches, memorial sites and meeting grounds. That asphalt could hold grief and strategy in equal measure. That when institutions failed, strangers would show up with water bottles and megaphones and portable speakers blasting Kendrick or Nina or Sam Cooke.

Now, five years later, that energy is reshaping itself into blueprints. Abolition geography, as Ruth Wilson Gilmore would say. Turning theory into curb cuts and cooling centers. Turning protest into budget line items that say: more trees here, more shade here, less police here, more playgrounds here. In Los Angeles, organizers are mapping “shade deserts” and demanding justice measured in square feet of canopy coverage. In Baltimore, activists dismantle hostile architecture and fight for benches where elders can sit without fear of harassment. Heat resiliency plans are being drafted in Houston, Miami, and Atlanta, but only because communities fought for them.

This is the work of unbuilding the wall—not just at the border but in our neighborhoods, policies, and collective imagination.

It looks like tearing down the barriers between neighborhoods and replanting connections. It looks like open-air markets instead of traffic corridors. It looks like turning cul-de-sacs into community gardens. It looks like outlawing design that punishes poverty—spiked window sills, unshaded bus stops, and park closures after dark. It looks like an investment in the places people gather: stoops, corners, front steps, basketball courts, the stretch of sidewalk where old men play dominoes and teenagers blast music too loud but with too much joy to stop.

It means not letting federal budgets decide who can breathe easy this summer.

It means pushing back against every dollar funneled into defense contracts, wall maintenance, and corporate tax cuts, and fighting for shade equity, air quality, and free, accessible THIRD SPACES where Black and brown life can stretch out and exist without fear.

It means remembering that public space is where freedom rehearses itself.

So this July, as the heat index climbs and the Senate tries to pass its Big Beautiful Bill, I’m considering other kinds of bills. I’m thinking about shade, clean air, and reparations bills written in the language of trees and playgrounds, open hydrants and free transit, longer library hours, and fewer cops with riot shields.

I’m thinking about every stoop I’ve ever sat on and every street I’ve ever marched down. I’m thinking about the block in Do the Right Thing, still standing the morning after the riot, still gathering breath for what comes next.

The temperature is rising. The bill is on the floor. But we’re still here.

And this time, we’re writing our own blueprints.

Until next time,

Marley

If this piece moved you, taught you something new, or just made you pause and breathe for a second, consider subscribing to THIRD SPACE.

Paid subscribers make it possible for me to keep writing these longform, research-heavy essays that center Black history, art, survival, and future-making.

And if you want to help keep me caffeinated (or help cover the next archival paywall I hit at 2 a.m.), you can buy me a coffee here.

you connect ideas across time periods, spaces, and disciplines so effectively! the idea of "social thermodynamics" is not one i'd heard before but it makes so much intuitive sense and i'd like to explore it further.

Beautifully written.