The Land They Forgot to Map, Part II: Drawing It Anew

Cape Verde wasn’t missing—just misrepresented. From Bela Duarte’s tapestries to Amílcar Cabral’s vision, I trace the art, memory, and resistance that put us back on the map—in our own image.

Growing up in New Jersey, I felt myself suspended between the map and the memory.

At school, I was Cape Verdean-Jamaican-American, a phrase few of my classmates could place. “Cape what? Is that near the Caribbean?” I learned to simplify. “West African & West Indian.”

But the truth was more oceanic than national. We were from a place between places—unmoored but not unrooted. The textbooks didn’t mention us. But the church pews did.The kitchen tables did. The tides did.

In our house, the islands survived. At the end of every party, there was always a plastic container of jag left behind—lukewarm, dense with flavor, its steam fogging the lid. I’d wake to it reheating on the stove, the scent of spiced rice and beans curling into the corners of the room like a memory we kept eating.

I didn’t speak Creole fluently, but that word—sodade—settled into me like a second heart. It wasn’t a language I was taught, but one I felt. It means a kind of longing that doesn’t want resolution—missing a place, a person, or a time so deeply that the ache becomes part of you.

Even without full fluency, I knew what it meant in the way my elders sighed when they said it. Through food, sound, and silence, we inscribed a kind of family cartography—a private geography of belonging on top of the blank spaces around us.

The Woman Who Wove Us Back In

Candy Seller (2003), a dyed-wool tapestry by Cape Verdean artist Bela Duarte, presents a single seated figure rendered in lush, fragmented color. A woman sits—not in a market or street, but in an imagined interior, anchored and unbothered. Her body is made of curved planes: rich ochres, deep purples, and blushing pinks collaged into a posture of quiet possession. In her lap, she cradles a bowl of round pink sweets, as if offering them—or guarding them. Her gaze meets ours, but only briefly, before slipping past—self-contained, unreadable.

What first seems abstract reveals itself, slowly, as deeply intimate. The crossed legs, the open chest, the loosely held sweets suggest pause rather than performance. This is not a portrait for the public gaze. It’s a moment stolen from daily life, rendered monumental through texture and color. The plant at her side, the window behind her, the light brushing on her skin—all suggest interiority. A room, not a street. A quiet morning, not a market.

The candy itself becomes something more than sweetness—it’s inheritance, offering, labor. Not just treats for sale, but symbols of care-work, informal economies, the maternal labor that makes culture survive. Duarte’s palette turns the mundane sacred. In this image, the candy seller is not spectacle. She is archive.

Like so much of Duarte’s work, Candy Seller is a reclamation—not just of Cape Verdean craft, but of Cape Verdean presence. It says: here is a woman, whole and unbothered, in a room of her own. She is not waiting to be mapped. She is already there. Holding sweetness. Holding story. Holding it all together.

Candy Seller speaks through lineage. Through the hands that made it, and the life that shaped those hands.

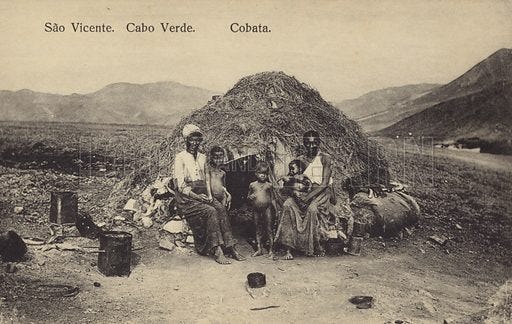

Bela Duarte has been a guiding star in my exploration of identity. Born in 1940 on the island of São Vicente, she came of age in the late colonial era and, like many of her generation, left to study abroad (in Lisbon) before returning home after independence.

In 1976, shortly after Cape Verde won freedom from Portugal, Duarte and fellow artists founded the Cooperativa da Resistência – “Resistance Cooperative” – which later became the Centro Nacional de Arte, Artesanato e Design. Their mission was to preserve traditional Cape Verdean crafts and arts that had been marginalized under colonial rule.

Even as the new nation was charting its political future, these artists were mapping a cultural one—reviving handmade weavings, batik textiles, and wood carvings: the ordinary arts of everyday life. Duarte taught weaving and batik, passing down techniques that carry collective memory in their patterns. Her very medium, textile, is about intertwining threads into a unified piece – a perfect metaphor for a fragmented history woven back together.

In Candy Seller, that ethos comes alive. The tapestry’s layered, mosaic quality mirrors how Cape Verdean history has always been told—in fragments, across generations, stitched from scraps of memory that rarely made it into the archive. Duarte doesn’t elevate the extraordinary; she honors the ordinary—and insists that it, too, is sacred. The woman in the image isn’t honored by title or fame—she’s simply seated, alone, steady. A bowl of sweets rests in her lap, not as product but as inheritance. It’s a quiet insistence: that this, too, is history.

Her tapestry doesn’t just show a woman selling candy—it shows a woman holding culture. She reminds us that our stories are made not only of resistance and revolution, but of routine: the lullaby at dusk, the taste of sugar on a child’s tongue, the rhythm of daily survival.

Duarte’s work—and that of other Cape Verdean artists—also renders diaspora visible. In the exhibition Claridade: Cape Verdean Identity in Contemporary Art (named after the iconic 1930s literary journal that sought to illuminate Cape Verdean life under colonial rule), artists from across the diaspora contributed their visions.

A dozen creators shared work shaped by diasporic experience: a video installation by a Rotterdam-based filmmaker of Cape Verdean descent; a mixed-media painting by a young artist born in New Bedford; Bela Duarte’s Candy Seller tapestry, on loan from a local collector. The dialogue between these works was palpable—mapping a people’s story across continents and mediums.

In an exhibition review, I remember reading a painting’s title that struck me deeply: “Partir mas ter que ficar” – Portuguese for “Leaving but having to stay.” The artist, Gilda Silva Barros, had painted it in 2023, but that sentiment spans generations.

Leaving but having to stay.

The phrase perfectly captures the diasporic condition: when you migrate, part of you leaves and part of you remains rooted in the homeland. You live in two places at once, belonging and not belonging everywhere. It’s a feeling my family knew well. Seeing those words in a museum, I felt seen – as if someone had finally put a pin in the map for us, naming that liminal space we inhabit.

What these artists are doing is, in a sense, drawing a new map – not one made not of geography but of connection. Instead of the Mercator projection or colonial charts, this is a map of the Cape Verdean diaspora’s heart. Lines are drawn not between capitals, but between stories and experiences: Praia to Providence, Mindelo to Rotterdam, Fogo to Boston.

In academic terms, one might say they are engaging in diaspora mapping theory – creating representations of belonging that defy physical borders. The philosopher Édouard Glissant, writing of Caribbean and African diasporas, offered the idea of “archipelagic thinking” as a counter to continental, colonial perspectives. He suggested that our identity can be like an archipelago: multiple islands of experience linked by the sea of story and relation, rather than one monolithic continent.

Such a worldview allows each person to be, in his words, “there and elsewhere, rooted and open” at the same time. I think of Bela Duarte this way. She was rooted in São Vicente, yet open to the world; trained in European techniques, yet committed to creole Cape Verdean expression.

The tapestry of the candy seller is local and specific – there – yet it speaks to anyone who has felt the pang of a half-forgotten home – it is also elsewhere. It is “rooted and open,” bridging a past community and a global audience. In reclaiming our fragmented history and placing it on gallery walls, artists like Duarte perform an act of cartographic justice: they put us back on the map, in living color.

Amílcar Cabral: The Revolutionary Who Believed in Culture

In the tangled sea of our history, one figure stands out: Amílcar Cabral (1924–1973). He was more than a guerrilla leader—he was a poet, agronomist, teacher, and philosopher. Born in Guinea‑Bissau to Cape Verdean parents, Cabral studied agronomy in Lisbon before returning home to map the land—and the soul—of his people. He co-founded the PAIGC (African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde) in 1956 and led the revolutionary struggle against Portuguese colonial rule through showdowns in the forest and strategic diplomacy across Africa.

He was in 1973, and never saw his homeland fully freed—but his ideas continue to ripple across generations.

What set Cabral apart was his insistence that culture is not decoration but weaponry. He wrote that “culture is, perhaps, the product of this history just as the flower is the product of a plant”—and that culture “contains the seed of resistance which blossoms into the flower of liberation.”

To him, decolonization was not only about guns or borders, but about reclaiming language, music, storytelling, farming, and self‑knowing. By teaching his soldiers modern agriculture alongside guerilla tactics, he was rebuilding both land and spirit. This was Cabral’s genius: treating the archive of everyday life—the infant lullabies, the farming traditions, the communal meals—as revolutionary territory.

When I trace a map with my finger, I inherit this practice of quiet resistance. I remember that global fascism, like old colonial frameworks, still tries to streamline us into invisibility. But when we say we were here, we are here, we follow Cabral’s lead. We produce a cartography of culture that asserts: our survival, our tastes, our tongues—are forms of defiance.

In these moments—stirring spices from our kitchens, teaching half‑Creole phrases, honoring our mother’s mother’s and their invisible labor—we are continuing Cabral’s work. We are refusing the erasures. We are mapping liberation, tile by tile: one story, one meal, one embroidered memory at a time.

Belonging in the Third Space

My father developed a habit of pouring over an old nautical chart of the Atlantic that he’d picked up at a yard sale. Perhaps it reminded him of his youth at sea, or maybe it was a way to jog fading memories.

One evening I found him tracing a route on that map with his finger – from New Bedford’s port back to Praia, the capital of Cape Verde. The distance between the two looked impossibly large on paper. He sighed and said to me, “You know, no map can really show how far we’ve traveled.” I understood that he meant more than miles.

The journey the Dias’s and Brito’s made – from a colonized speck of land not even printed on some maps, to a life in America building everything from scratch – was an Odyssey of the spirit.

No map could capture the exile, the resilience, the in-between-ness of that journey. In that realization lies a kind of wisdom: the recognition that maps, as traditionally drawn, have their limits. They cannot chart longing. They cannot mark belonging. They cannot measure the weight of sodade in a migrant’s heart.

If the old maps forgot us, we learned to refuse their tyranny. We claim the right to remain partly uncharted – to exist in what Homi K. Bhabha famously called the “third space,” a space of hybridity beyond the neat lines of nation and identity.

Growing up, I often felt neither entirely Cape Verdean nor entirely American, but something else – a third thing,at once both and neither. That used to make me uneasy, as if I had no place. Now I see it as a source of power. I carry multiple places within me.

My map is not one of borders and exclusions; it is a constellation of connections. Belonging, I’ve learned, is not always about having a place on the official map. Sometimes it’s about making a place in the gaps where the map falls short.

I belong in the stories I’ve inherited, in the community that recognizes the same songs and foods, in the art that speaks to our shared history. In that sense, I belong everywhere my people are, and they are scattered like stars across many skies.

Towards the end of writing this, I find myself dreaming of that old nautical chart my father cherished. I imagine running my fingers over the latitude lines spanning from New England to West Africa. I think of all the unnamed journeys, the unmapped experiences, that lie between those lines. The map is a useful tool, but it is also a metaphor – one I can both use and resist.

So I return to the map, both as metaphor and as refusal. I imagine picking up a pen and sketching new markings on it: here, a tiny star for every Cape Verdean enclave in the diaspora; there, a gentle wave pattern for each cultural memory that flowed across the ocean; an X for the port in New Bedford where Cape Verdean sailors once landed, another for the harbor in Mindelo where Eugenia watched ships depart and dreamed of her own departure.

This would be our map – messy, crisscrossed, alive. It would defy the clean, empty spaces of the old imperial charts. It would refuse to keep us invisible.

In the end, The Land They Forgot to Map is no longer forgotten. We remember ourselves. Through the intimate cartography of story, through the intellectual labor of historical critique, through the expansive creativity of art and imagination, we have redrawn the boundaries of who we are. We have marked the spots that were left blank. We have named the unnamed and colored in the margins with our lives.

My great-great grandmother’s journeys, Bela Duarte’s tapestries, my own Jam-Verdean childhood – these are the legends on the new map of Cape Verde that lives in me. And if that new map does not fit neatly into the old frames, so much the better.

There is power in opacity – in not being completely known on someone else’s terms. We owe nothing to the Mercators of the world who would shrink or omit us. We chart our own course. We exist in relation to one another, across shores and generations, in ways that no Mercator projection can ever flatten.

I fold away the nautical chart and see, in my mind’s eye, a different image: an archipelago of islands connected by threads of memory stretching over the sea. A great weaving, like Bela Duarte’s tapestry, linking island to island, person to person.

This is the map I choose to navigate by now. It’s a map that centers diaspora and all its paradoxes – leaving but having to stay, there and elsewhere. It’s a map that lives in stories and art, in an intimacy passed from parent to child, in a community that refuses to be lost.

Standing at that intersection of personal reflection, historical critique, and cultural theory – that third space – I feel both small and infinite. I whisper the names of the islands like a litany: Santiago, São Nicolaou, Santo Antão, Fogo, Brava. Each name a beacon that colonial maps could not extinguish. Each name a piece of me.

The land they forgot to map was here all along, quietly enduring outside the margins. And now, through the alchemy of memory and art, that land is mapped in us – intimate, intellectual, expansive – a world reclaimed, a name and a home found again.

We were never truly off the map. We were simply drawing it anew, in our own image, all this time.

Until next time,

Marley

If this piece moved you, map your support below.

📌 Subscribe to Third Space — where memory, art, and diaspora meet. It’s free to follow along, and paid subscribers help keep this work going.

🍲 Buy me a jag — or a coffee, or a thread to stitch the next story together: coff.ee/marleyd

Every subscription, share, and kind word redraws the map with us.

Thank you for being part of this living archive.

Edited by Luke Wagner, special thanks to my homie.