The Land They Forgot to Map

When colonial maps left Cape Verde blank, we stitched ourselves back into history.

The Cartographic Lie

I was nine years old, standing before a faded classroom globe in West Orange, NJ, when I realized the land of my father’s family was missing. My fingertip hovered in the blue Atlantic, searching for the speck of islands off the African coast that I had heard about in family stories.

Cape Verde – a name that sounded like an incantation – was nowhere to be found on that map. At most, there was a tiny dot without a label, or an off-margin footnote. In that moment, I felt invisible, as if a part of me had been erased by the flattening gaze of the mapmaker.

My peers moved on, pointing out big continents and capital cities, while I kept glancing back to that blank patch of ocean where home should have been. It was as if the map had quietly decided that my father’s homeland didn’t matter enough to merit ink.

At home, by contrast, Cape Verde (Cabo Verde in Portuguese) was everywhere—unseen by others, but vivid to us. My father would close his eyes and draw an invisible map in the air, recounting how our ancestors would sail from island to island under constellations that he knew by name.

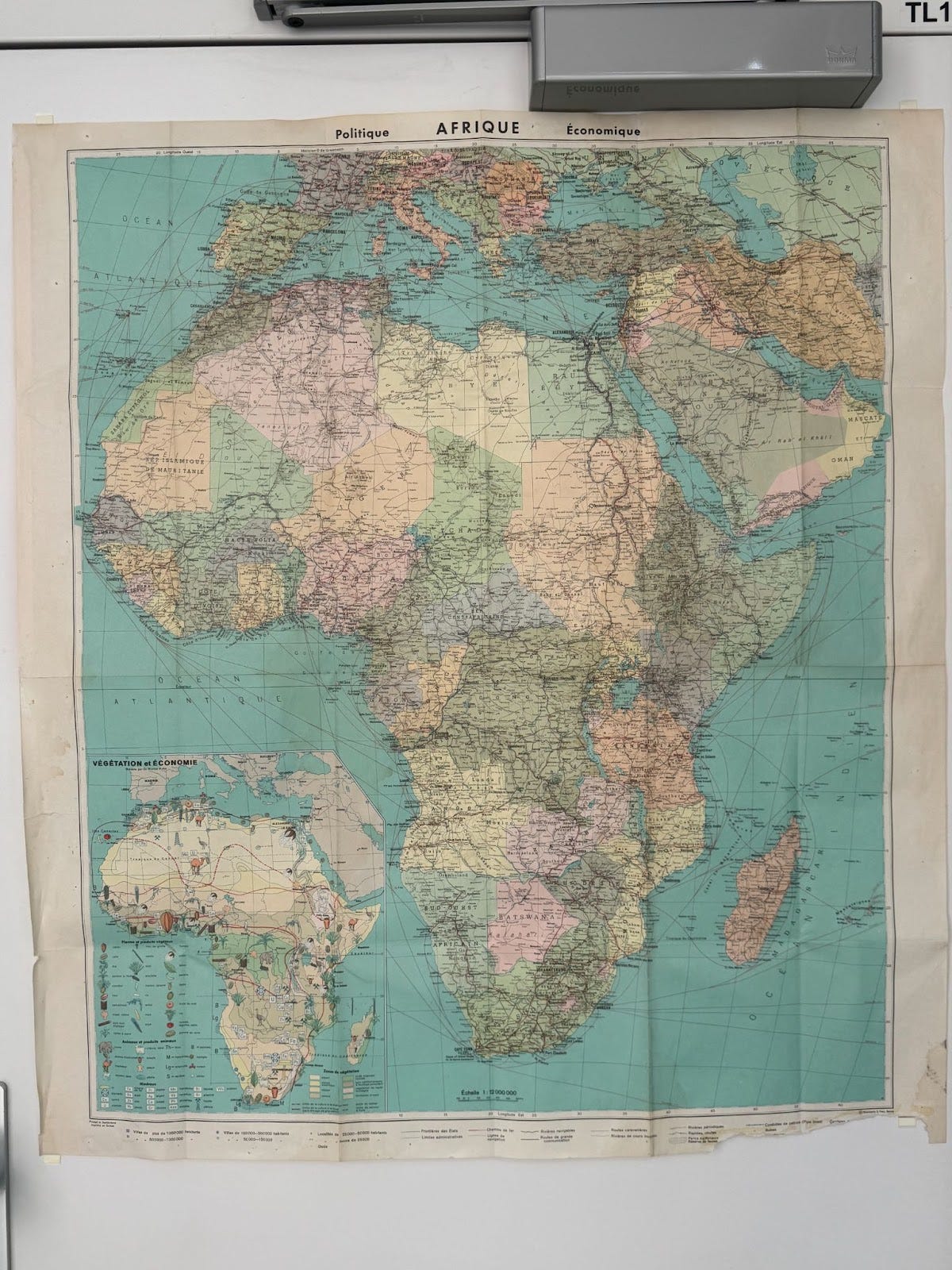

On our kitchen wall hung a small map; he gently guided his fingers and pointed to where the islands lay – “Right there, just off Senegal.” I would lean in close, squinting to see the pinprick of land.

Sometimes even the print was so small that Cape Verde blurred into the latitudes. My father would grin and assure me it was there. In his memory, the archipelago was enormous – each island a world of its own.

He spoke of São Vicente’s harbor at dawn, of grogue rum distilleries on Santo Antão, of the red earth of Santiago after the rain. These were sensory maps drawn from oral traditions: the smell of sugarcane molasses, the sound of mornas (our soulful songs) echoing at twilight, the sight of a lone baobab tree bending in the dry wind.

No official map could capture those details. And yet, in school, when I opened a geography textbook or looked at the world map tacked above the blackboard, I was confronted with absence. Cape Verde was the land they forgot to map – or perhaps, the land some had willfully erased.

That childhood dissonance planted in me a quiet ache. I felt the sting of irrelevance: if the map didn’t show our islands, did we truly exist in the eyes of the world? I didn’t have the words for it then, but I sensed a deeper story behind that omission.

Years later I would learn that maps are not neutral artifacts; they carry the biases of their makers.

The erasure and distortion of African places on maps has a long, troubled history.

My tiny homeland’s vanishing act was part of a larger pattern – one that I would spend much of my adult life trying to understand and ultimately to rewrite.

How Africa Was Erased on Purpose

Looking back, I realize that the blank space where Cape Verde should have been was not a child’s mistake but a colonial legacy. Historically, European cartographers often treated Africa and its islands as negligible details—or even as voids waiting to be claimed.

In the 19th century, maps of Africa famously featured vast white spaces labeled “unexplored” – a fiction that served European imperial ambition. Explorers and geographers at the time “repeatedly emphasised that the maps consisted of little more than just blank spaces which should be filled out” to open up trade and conquest.

Tellingly, those blank spaces were not merely reflecting ignorance; they had to be created. Earlier maps of Africa (for example, a 1737 map by German cartographer Johann Hase) were actually filled with speculative information from travelers like Leo Africanus – rivers, mountains, kingdoms drawn in vibrant if imperfect detail.

But by the 1800s, European mapmakers began omitting indigenous names and landmarks, replacing them with voids labeled terra incognita. This deliberate simplification made Africa look uncivilized and ripe for conquest.

The erasure was strategic. A blank map was a political message: Here is a land with no history, no people of importance – a land awaiting our maps and our rule.

Such cartographic distortions did not only apply to Africa’s vast interior. They extended to the margins, to the islands and small nations that colonizers deemed peripheral.

My father’s homeland, an archipelago of just over half a million souls, was one such place. Many world maps simply cropped out or ignored the islands of Macaronesia (the Cape Verde islands along with the Canaries, Azores, etc.), focusing only on mainland Africa.

Even today, the “conventional portrayal” of Africa in maps often does not show the continent’s Small Island Developing States (SIDS) such as Cape Verde, São Tomé and Príncipe, Guinea-Bissau, Comoros, Mauritius, and Seychelles.”

In adapting maps to fit a page or screen, “small states often disappear.” The omission is usually not malicious – it’s an artefact of scale and convenience, we are told. But intention doesn’t cancel impact. The effect is the same: a quiet reinforcement of the idea that these places are marginal, unseen, barely real.

When small islands do appear on common maps, they are often reduced to insignificant dots, divorced from context. I recall a Mercator-projection world map hanging in my high school – the kind so ubiquitous that few stop to question it. On that map, the relative sizes of continents were wildly skewed. Africa, which is in reality enormous, was rendered so small that you could blink and miss Cabo Verde altogether. (Greenland, for instance, appears roughly equal in size to Africa, though Africa is fourteen times larger.)

Developed in 1569 for navigation, the Mercator projection stretches space as it moves away from the equator, inflating Europe and North America while shrinking Africa. The result is a world subtly centered on Europe – a warp that “pumps up” the global North and diminishes the Global South. On that classroom wall, Europe loomed large and Cape Verde was a minuscule footnote at the map’s frayed western edge.

That was the first time I felt, viscerally, how distortion becomes perspective—how a shift in scale can make entire peoples vanish.

This was the legacy of colonial mapping systems: a legacy of distortion and erasure. Maps renamed places—Cape Verde was named by Portuguese navigators after a green cape on the African mainland, as if the islands had no identity of their own. They drew borders straight through indigenous lands, and left out any details that didn’t serve European interests.

Cape Verde was “discovered” by Portuguese sailors in the 15th century and turned into a hub of the transatlantic slave trade. But you won’t find the stories of those enslaved souls on any old maritime chart. Instead, antique maps might show a clump of islands with the Portuguese names – São Tiago, Boa Vista, Fogo – and maybe a note about fresh water or safe anchorage for ships.

The rich African and creole culture that blossomed there over centuries was entirely absent on those maps. To the cartographer, we were just stepping stones in the ocean or strategic supply stations on the route to somewhere else.

No wonder generations of Cape Verdeans grew up without seeing themselves in the official record. We were rendered invisible on paper long before I felt that sting in a fourth-grade classroom.

Finding Our Way Without Maps

My father carried these historical erasures in the lines of his face, though I didn’t understand it as a child. He was born in New England—not on the islands—but still carried Cape Verde in his posture, his voice, his silences.

Our family came from São Nicolau in the 1940s, part of the long migratory tide of Cape Verdean whalers who crossed the Atlantic not in search of freedom, but out of necessity. The very climate of the islands conspired to push people away. Droughts, famine, and a shrinking economy forced generations of Cape Verdeans to sea.

They worked aboard American whaling ships, on merchant routes, in canneries and factories from Mindelo to New Bedford. São Nicolau men were known to be skilled and steady, and they traveled far—leaving behind their families with the hope of sending something back.

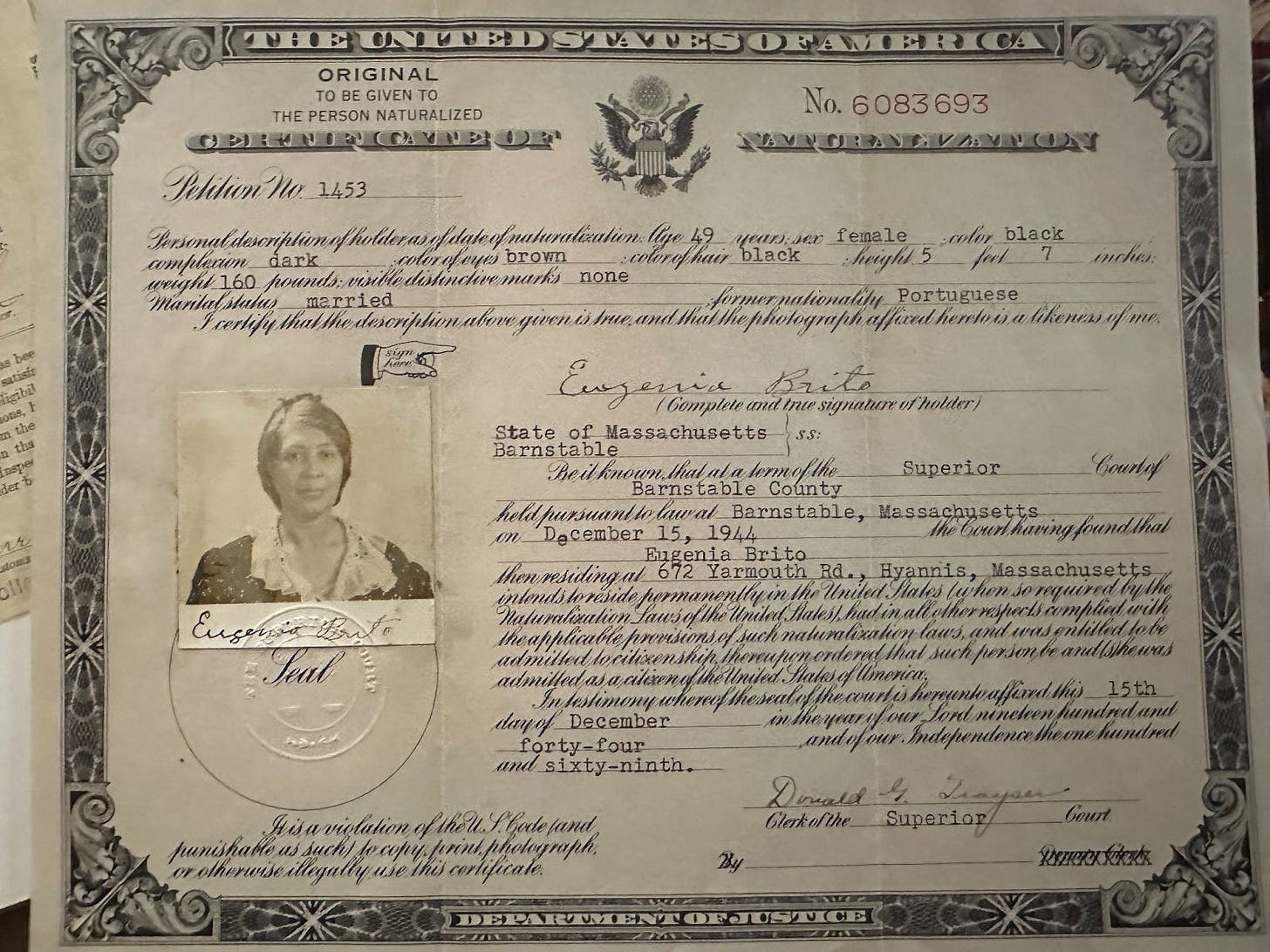

That’s how my great-great-grandmother Eugenia Brito arrived: through the Atlantic corridor of survival. In 1944, she became a U.S. citizen in Barnstable County, Massachusetts. Her naturalization certificate, printed in fine bureaucratic script, lists her as a “49-year-old female” of “former nationality: Portuguese”—a classification that erases as much as it reveals.

She was Black. She was Cape Verdean. She was fluent in a language the courts couldn’t pronounce. That piece of paper may have legalized her presence, but it didn’t make room for her story.

My father was born into the aftermath of that journey—raised in Massachusetts by Cape Verdean women who fed him slow-cooked cachupa and told stories with their eyes more than their mouths. He didn’t speak of “immigration” the way other families did. The journey was old by then.

But even as an American-born son, he moved through the world like someone who had crossed water. There was a quiet knowing in him, an archipelago logic: fragmented, scattered, always returning.

Maybe that’s why, later in life, he became a geographer. He studied Earth and atmospheric sciences—not just the land, but the weather that shapes it. It always struck me as poetic: a Cape Verdean boy, descended from sailors and islanders, choosing to chart the very forces that once scattered his ancestors across the Atlantic.

The maps that had failed to include him? He learned how to redraw them.

He rarely explained where we came from in so many words. But I learned anyway. In the way he tied knots without looking. In the way he could gut a fish with two strokes of a blade. In the way he rose early, not to pray, but to watch the tide. In the way he lowered his voice when white people were around. These were his coordinates.

Yet memory can be a fractured map. There were things he chose not to remember out loud. I didn’t know until later that famine had devastated the islands in the late 1940s—shortly before Eugenia’s migration.

He never told me that hunger could follow a family across generations, not just in stomachs but in habits—the way we never wasted food, the way silence settled over certain stories.

Instead, he spoke of joy. Of the resourcefulness of our people. Of living room dances and clam bakes. Of grandmothers who could stretch a dollar and a pot of beans for a week.

I think now of a line by Saidiya Hartman:

“Every generation confronts the task of choosing its past. Inheritances are chosen as much as they are passed on.”

My father chose what to carry. He remembered the music, the parties, the moonlight off the bay. He left unspoken the hunger, the grief, the ocean crossings made in desperation. In crafting his stories, he wasn’t denying history—he was remapping it, offering me a version I could grow inside.

If this piece moved you, map your support below. Part 2 releases Wednesday.

📌 Subscribe to Third Space — where memory, art, and diaspora meet. It’s free to follow along, and paid subscribers help keep this work going.

🍲 Buy me a jag — or a coffee, or a thread to stitch the next story together: coff.ee/marleyd

Every subscription, share, and kind word redraws the map with us.

Thank you for being part of this living archive.

Until next time,

Marley

Edited by

, special thanks to my homie.

I love these pieces about cultural erasure. This theme is surely book long. Charlotte

So glad that your father remembered the music, the parties and the moonlight on the bay.