After the Gallery Doors Open

I stand in a hushed London gallery before Home: As You See Me by Njideka Akunyili Crosby. A room split between velvet curtains and the flicker of TV screens, brown sofas dressed in lace doilies, their edges curling like pressed flowers.

On the wall, Dora Akunyili’s face repeats in regal defiance—Service to the People encircling her like a halo. The entire surface is layered: family portraits on television sets, political heroes woven into wallpaper.

History sinks beneath the tiled floor in photo clippings and printed memory.

The room is both witness and altar, living room and archive. And I find myself thinking about all the rooms we’re expected to perform ourselves in — the homes we build, the stories we hide in plain sight. The past hums quietly in the air conditioning. A nation dreams between the folds of the curtain.

I step closer. In the quiet of this hall, the layered faces in the work seem to whisper.

They mingle with the morning headlines still ringing in my head: distant explosions, children lost in Gaza, villages burned in Sudan, lives shattered in Congo. At this moment, the girl in the painting and I share the same uncertainty. Surrounded by all this beauty and stillness, I feel the tremor of everything unsaid.

The museum is silent, but I know that silence isn’t neutrality—the museum was never neutral.

These horrors throb in my chest as I stand here, yet around me the plaques and captions speak of empires and art movements as if pain were only a relic of the past.

A class of schoolchildren shuffles by a portrait of an 18th-century nobleman—his powdered face immortalized in oil, his colonial wealth left unquestioned.

They pause briefly, listening as a docent describes his contributions to the arts, never mentioning the enslaved labor that funded his estate.

I watch their eyes move from frame to frame, and I wonder: what are they learning to value? What absences are being naturalized as normal?

This is how the museum teaches—quietly, implicitly. It tells us what counts as history, and by omission, what does not. The museum doesn’t need to lie outright; it only needs to curate selectively. And so the unspoken rule is passed on: what’s on the wall matters. What’s not is forgotten.

No Plaque for the Living

I remember reading a label on a looted Benin Bronze in another gallery, praising the object’s craftsmanship but omitting the blood spilled when British soldiers took it.

Even the facts a museum omits are part of its tale.

I catch my reflection in the painting’s glass—a Black girl with a sorrow in her eyes that I can’t quite hide. Some of that sorrow is personal, but much of it is collective—a global grief I carry for those I’ve never met.

It’s the weight I felt seeing the aftermath of earthquakes that flattened entire neighborhoods in Syria and Türkiye, where families dug through rubble with bare hands. It’s the emptiness I felt watching video of a boat carrying Rohingya refugees—men, women, children—vanish into monsoon waters, their names likely never to be recorded. It’s the ache that settled in my chest when I saw the remains of an apartment building in Rafah, Gaza, after an airstrike turned it to dust.

These moments don’t get museum wings or bronze plaques. They flicker across screens and vanish. But I carry them. They are part of my emotional archive—a record of whose suffering is witnessed, and whose is quietly erased.

In these polished galleries, there is no trace of that grief. No memorial plaque for those children. No acknowledgement they ever existed.

Naming the Lost

One rainy afternoon I visited Tate Modern, drawn by an exhibition of Lubaina Himid. The moment I stepped into her installation Naming the Money, I felt I was walking into a chorus of whispers. Life-sized painted figures surrounded me—Black servants and enslaved artisans from centuries past, each one brought to vivid life.

I pressed my hand to my heart as I read their stories, feeling grief and solace intermingling.

In that gallery, those who had been invisible in history stood tall, demanding remembrance. Himid’s work felt like an act of radical care: a curatorial love letter to ancestors, a refusal to let their names be lost.

She showed that a museum can hold space for erased lives—so why can’t it also hold space for the suffering happening now?

In Naming the Money, Lubaina Himid doesn’t just depict Black subjects—she resurrects them. Her figures, life-sized and hand-painted, stand proudly with names and stories, refusing the anonymity that so often swallows the enslaved in Western art history.

The installation doesn’t whisper; it confronts. Each plaque tells you who they are, what they were forced to become, and what they could have been—a ceramicist, a musician, a painter.

But it’s not just the figures that do the work. It’s the context.

The museum becomes a stage for reckoning. Himid turns its usual power—its ability to frame, caption, and curate—on its head. She uses that institutional authority to name what was stolen, and to return dignity where it was denied. For once, the museum amplifies rather than erases.

So when institutions claim they can’t "take a stance" on ongoing atrocities—when they say it’s not their place to speak on Gaza, or Tigray, or Haiti, or Uvalde—I remember Naming the Money. I remember that Himid’s work shows it is entirely possible. Museums are not powerless. They choose what to include, what to soften, what to make visible.

Lubaina Himid proved that remembrance can be radical—and that curation is never neutral.

Rooms of Absence

That question traveled with me to Geneva. I went to the International Red Cross Museum, expecting a shrine to fulfill their humanitarian ideals.

Inside, one room was quieter than the rest. A curved wall held rows and rows of faces — passport-sized photographs of the missing, each one clipped to a card, each one staring back without answers.

Beneath them, long black tables held thick ledgers and consultation drawers, names alphabetized and annotated, waiting.

The installation was called Tracing the Missing, designed by Diébédo Francis Kéré.

I moved slowly past the records, my fingers grazing the edge of an open book. Some names had been marked as found. Others remained blank. I stood there for a long time, absorbing the enormity of absence. So many faces. So many silences. It didn’t feel like a monument. It was a silence that demanded an answer.

The museum presented these stories with compassion—yet also with careful neutrality. The plaques spoke about “the cost of conflict” and “humanitarian aid,” but never named the perpetrators or the political causes. I understood why—the International Red Cross must remain neutral to operate in conflict zones. It’s part of their founding principles: neutrality allows them to gain access to all sides of a war, to deliver aid without being expelled, targeted, or seen as taking a political stance.

But even knowing this, I felt a knot of frustration in my chest. Because while neutrality might protect operations, it can also obscure responsibility. In the silence of the exhibition, no one was blamed. No governments were held accountable. The human cost was displayed—rows of faces, missing names—but the systems that made them disappear were left unnamed.

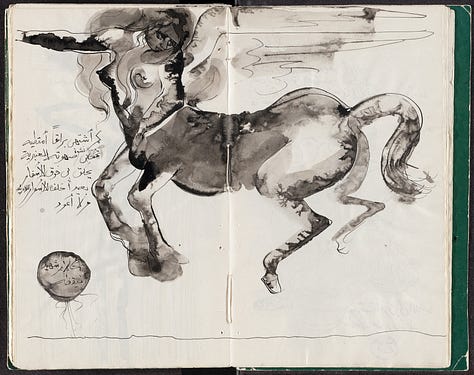

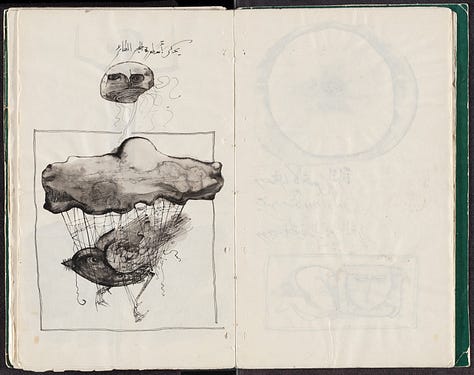

That tension—the ache of witnessing without naming—followed me across borders. A few weeks later, I found myself in New York’s MoMA, still turning over the silences I’d seen in Geneva. There, behind a small glass case, lay another kind of testimony: a worn notebook, opened to a spread of dense ink drawings and looping Arabic script. It was the prison diary of Ibrahim El-Salahi.

The pages were filled with contorted figures packed behind bars, a tiny bird caught in a net, and verses of Arabic poetry sketched in the margins.

I imagined the artist in 1970s Sudan, crouched on a cell floor with only a stub of a pen, risking punishment to record each day’s despair.

He buried these drawings in the dirt to hide them from the guards. Now here they were, preserved under bright lights. I felt pride that his testimony survived—and hollowness, knowing how many others never will. Ibrahim later said he drew so he wouldn’t forget, so none of us would forget those unjustly imprisoned.

I mouthed those words as I looked at the notebook, a silent promise to remember. Sudan is in turmoil again today—new wars, new prisoners, new innocents.

I wondered if somewhere in Khartoum, another artist sits in a dark cell scratching out a hidden diary, hoping that someone, someday, will see and remember.

⟶ Been thinking about museum memory too? Leave a comment. I’d love to hear what this stirs up for you.

A Museum We Haven’t Built Yet

Leaving MoMA, I walked down the busy Manhattan sidewalk feeling the weight of El-Salahi’s witness.

Museums enshrine certain tragedies and ignore others. We have museums for tragedies that shook the West—but where are the exhibits for the colonized and bombed?

Where is the gallery for Gaza’s children, for the families drowned crossing the Mediterranean, for the Rohingya forced into camps, or the Haitians displaced again and again by crisis and neglect? Where is the room for the disappeared in Sri Lanka, or the Uyghur poets silenced in Xinjiang?

I imagined what it would mean for a young Black girl—or any girl from a war-torn or colonized place—to walk into a grand museum and see her own grief reflected with dignity. Not as a footnote or a tragic backdrop, but as part of the human story—curated with care, not pity.

Because framing matters. When museums choose to historicize one group’s suffering and ignore another’s, they don’t just archive the past—they shape whose lives are seen as worthy of remembrance. To be left out is to be told, quietly but powerfully: your pain is not timeless. It is not art. It is not ours to hold.

That acknowledgement is a kind of love—a validation that her suffering matters and won’t be dismissed as “too political” for art.

In October 2023, a vigil was held in London’s Parliament Square to honor children killed in Gaza.

Each participant wrote the name of a deceased Palestinian child on their hand, echoing the heartbreaking practice of children in Gaza who wrote their names on their palms so they could be identified in death. It was a grassroots memorial standing in contrast to institutional silence.

This act of remembrance was more than symbolic—it was a silent protest against the erasure of these young lives, a grassroots memorial built out of bare hands and black ink.

It stood in stark contrast to the silence of major institutions—museums, governments, cultural gatekeepers—that claim to preserve memory, yet so often look away when the memory is too politically inconvenient. While children in Gaza wrote their names on their palms to be identified in death, the walls of our most celebrated museums remained clean, untouched, and quiet.

Inside the Museum of Care and Refusal

All these moments and images knit themselves together in my mind, forming a tapestry of both pain and hope. I begin to envision a different kind of museum—a museum of radical care and refusal.

It doesn’t exist yet except as a dream, but I can see it so clearly. It’s small and unassuming, tucked on a side street in a bustling city, perhaps in a refurbished old house. The sign on the door says Museum of Care and Refusal.

Inside, the first gallery is warm with lamplight and alive with everyday beauty. On the walls, art celebrates the inner lives of Black women: a figure in a patterned dress sits quietly on a yellow sofa, her back to us, facing a black-and-white portrait of a mother and child.

The wallpaper wraps them both in ancestral presence — Dora Akunyili’s face appearing again, encircling them in a ring of Service to the People. The room is filled with silence and seeing.

Everything here remembers. The past is not behind her, but beside her. At the center of the gallery, on a low table, lie open diaries and letters under glass — fragments of lives lived fully and tenderly. Here, even quiet is curated with care.

Visitors can lean in and read a few pages: a child’s poem scribbled on the back of a food ration slip in a Gaza camp, a diary page from Ibrahim El-Salahi inked with barbed figures and hidden verses, a torn letter from a Sudanese doctor written on hospital stationery, corners smudged with dust and blood. Their handwriting is preserved and honored here. I notice a young man reading a letter, wiping tears from his cheek. Here, every voice carries weight.

Further in, there is a room painted deep blue—the memorial chamber. On its walls, names are projected in a slow, unending scroll. They are the names of people lost in conflicts that rarely earn monuments: names from Gaza, Darfur, Congo, Yemen, and beyond. A gentle voice reads them aloud like a litany.

In one corner, water trickles in a small fountain, the sound like quiet weeping. The atmosphere is solemn but compassionate; grief is not an intruder here. I see a girl my age kneeling by the wall, tracing a name with her finger. I understand. Here, remembering is not forbidden—it’s sacred.

In the next gallery, echoes of Lubaina Himid’s influence appear. Instead of historical silhouettes, there are life-sized portraits of people from today—an Afghan midwife who delivers babies in makeshift clinics, a Venezuelan musician who fled across three borders with his violin, a Congolese journalist who prints underground newspapers by hand.

Each figure is accompanied by a plaque telling their full story: not just the trauma they’ve survived, but the joy they protect—the lullabies they hum, the dishes they long for, the futures they still dare to imagine.

They stand not as victims of some distant story, but as full human beings in our present. This museum refuses to flatten people into symbols; it insists on their full humanity.

At the heart of the building is a small open-air courtyard. In it stands a single sculptural tree made of twisted metal and shattered glass—war debris welded into a leafless tree—entwined with living jasmine vines.

This artwork was imagined by an artist from Gaza, who forged beauty from the wreckage of a bombed-out home. Jasmine blossoms cling to the metal, perfuming the air. Paper cranes and handwritten notes hang from its branches—prayers, names, fragile hopes.

A plaque at its base reads: Even in ruin, we bloom.

And yet, this piece may never truly exist. The home it draws from may already be gone—flattened beneath the weight of drone strikes and phosphorus. Studios have been reduced to ash. Archives erased. Artists killed or displaced. The very possibility of cultural production—of telling the story—has been violently severed.

That’s what makes this sculpture feel sacred: not just what it represents, but what it resists. In the quiet of this courtyard, silence feels like healing. But beyond these imagined walls, silence is being forced—through rubble, censorship, and death.

And Still, the Magic

Before I go, I keep circling back to something Toni Morrison once said in an old interview — not about history or politics or art, exactly, but about fiction. She said:

“Its not possible to constantly hone on the crisis, you have to have the love, and you have to have the magic”

Toni Morrison (4:22)

I think about that as I walk through this imagined museum — because it is not just a museum of pain. It is a museum of love. Of defiant joy. Of jasmine growing through rubble. It is curated not with neutrality, but with care. With the belief that Black and brown life — in its fullness, not just its mourning — is worth archiving.

Morrison knew that art couldn’t only point to the wound. It had to conjure something beyond it.

That’s what this museum does. It holds the grief, but it also makes space for the magic. For the African mothers who serve their people. For the girl tracing names on a deep blue wall. For the softness that survives even when everything else burns.

And maybe that’s what I’m trying to do, too — here, now, with this story.

Because the museum was never neutral. And neither are we.

Until next time,

Marley

Let’s keep curating care — together.

THIRD SPACE is a reader-powered newsletter where memory, justice, and Black imagination meet.

📨 Subscribe here: marleyedias.substack.com

☕ Buy Me a Coffee? Help keep the jasmine blooming:

👉🏽 buymeacoffee.com/marleyd

⟶ Share this post with someone who believes memory matters.

⟶ Leave a comment if it moved you — your reflections mean the world.

⟶ Special thanks to

for his edits!

a beautiful piece... brings up memories of my visit to the holocaust museum in DC as a child. i don't cry easily, but the miniature scale models of gas chambers and the pile of shoes from children murdered in the camps brought me to tears. i don't know how to describe the feeling other than deep threads of ancestral memory reaching back across decades, as if inscribed on the genes i inherited from my russian jewish family. learning about genocides in a classroom allowed me to detach from them, to intellectualize them and trick myself into forgetting they were real. in the museum, i fused with the historical trauma of my people in a way that i never had before, and i try to return to that memory whenever i am reading about the holocausts in Gaza and Congo and Sudan. i have to combat the urge to detach, because it makes me feel like these ongoing atrocities are completely beyond my control, like we exist in different worlds, and that's simply untrue.

"not just the trauma they’ve survived, but the joy they protect" - this spoke so clearly to me. I hope this museum finds its way into this world. Thank you for your creation and virtual curation of it.