Too Grown to Breathe, Too Young to Quit

When "Black Girl Magic" becomes too heavy to hold: on maturity, burnout, and the quiet longing to disappear.

The Mask of Maturity

I’ve been called ‘mature for your age’ for as long as I can remember. As a little Black girl who could sit still through adult meetings, I was praised for my poise, unaware that praise was becoming a mask.

Beneath the compliments and gold-star behavior, a tender child did emotional labor beyond her years. I smiled through exhaustion. I aced presentations while my insides churned with anxiety. Being “mature” meant never letting them see you sweat, never letting them hear you sob into your pillow at night. Black girls, as research sadly confirms, are often seen as less in need of nurturing or comfort than their white peers.

I tucked away my childish needs and put on the mask. If I acted strong and unbothered, maybe I’d be strong and unbothered.

That mask was suffocating. I was too grown to breathe. In truth, I was holding my breath through anxiety and loneliness, hoping no one would notice the cracks. The world applauded my precocity but had no clue that each clap felt like cement being packed onto my chest.

I was living proof of what Saidiya Hartman calls the “practice of possibility at a time when all roads…are foreclosed.” I obeyed no childish rules; I was unrepentant in my drive to exceed expectations. Yet with each achievement, I felt the room for me-the real me—shrink. My so-called maturity became both armor and prison.

An Accelerated Life

By the time I was a teenager, I had launched a viral movement, published a book, and traveled the world as an activist. I was living what many called an accelerated life.

At 19, I was the youngest activist (by six years) honored at the United Nations’ Young Activist Summit in Geneva, addressing global leaders on representational justice. I felt honored—and completely alienated.

The night I returned from Geneva, I literally hit the ceiling—standing on a chair, I smacked my head on a full-speed ceiling fan. It left a Martha’s Vineyard–shaped scar and a concussion. I laughed it off, but privately it felt like a cosmic joke: too high, too fast.

When I reflect now, that concussion was a symptom of what my friend Molly calls “racing”. Racing is the inability to slow down and the insistence that moving faster will improve the result. That was me.

I was always racing to do more, be more, prove more. After Geneva, I “raced” to another event in New York, then back to school, as if momentum alone could hold me together. The world was collapsing—climate disaster, social unrest—and I felt I had to accelerate my contributions to keep hope alive.

But living at this speed had a cost. I was physically exhausted and emotionally brittle. On the surface, I was the energetic young changemaker, but inside, I felt like a withered balloon, barely floating.

Too grown to breathe, too young to quit. How could I, at 20, say “I’m tired” when so many people had invested hopes in me? If I dared whisper “I’m not okay,” I feared disappointing everyone who saw me as a prodigy.

So I kept racing—until my body and mind started staging minor mutinies. The concussions, the panic attacks at 30,000 feet, the nights of sobbing into hotel pillows in far-flung cities, wondering why the hell I felt so alone. I would stand on stages touting the power of youth activism, and later cry in the shower, feeling like a fraud.

The ideation crept in not as dramatic thoughts of self-harm, but as a quiet, persistent question: What if I didn’t wake up? Not because I hated life or failed at something, but because the pressure of performance was crushing me.

I realized something profound in those moments: my ideation wasn’t tied to any personal failure. It was tied to success. The more I achieved, the more isolated I felt, and the more it seemed I could never stop. How do you quit when the race has no finish line? When are you celebrated for running yourself ragged?

“i don't pay attention to the

world ending.

it has ended for me

many times

and began again in the morning.”

― Nayyirah Waheed, Salt

Anxious Men, Hidden Pain (Black Art Spotlight)

To help me confront this turmoil, I turned to Black artists who speak the language of anxiety and performance.

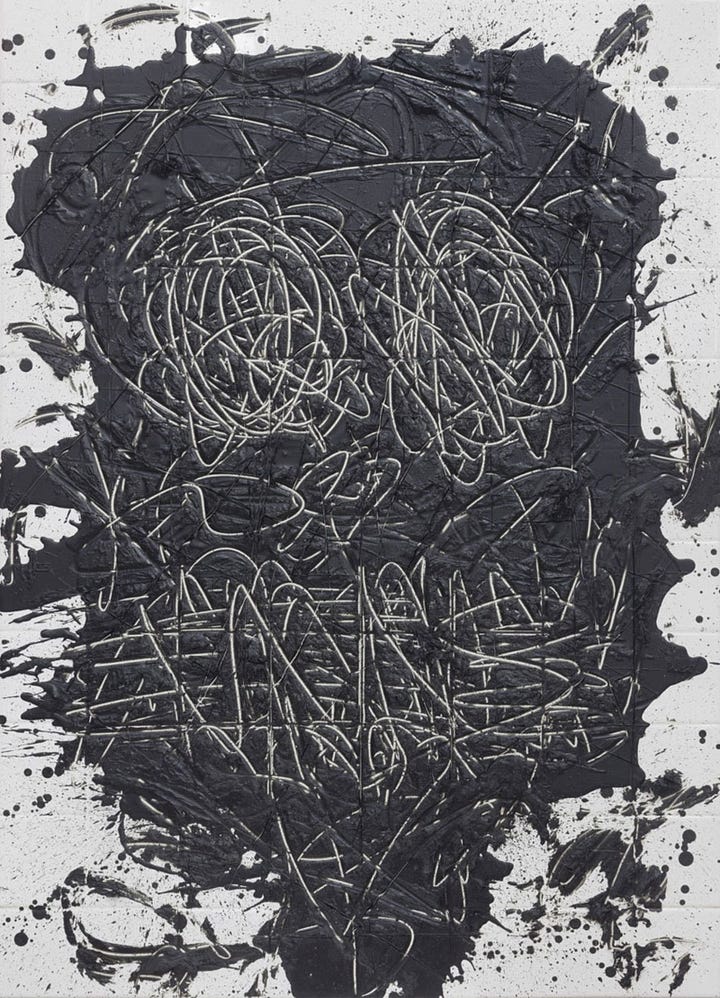

I kept returning to was Rashid Johnson’s “Anxious Men.” In this series, Johnson created portrait-like faces by scratching into a waxy black surface of black soap and wax. The resulting figures—his anxious men—are all jagged lines and wide eyes, their mouths in silent anguish.

They are crude and powerfully immediate, confronting the viewer with emotion. Johnson said these works were reflections of his anxiety and “what [he] believe[d] to be a collective anxiety.”

The figures in Anxious Men look like they’ve been clawing for air, dug out from beneath layers of wax. That was me: outwardly composed, inwardly clawing.

Johnson spoke of how showing his vulnerability as a man strengthened his work, and ideally gave viewers agency to express similar emotions. By scratching his pain onto tile, he permitted others to acknowledge theirs. I needed that permission. I needed someone to tell me that feeling broken or anxious didn’t make me a failure at being “mature” – it made me human.

The anxious faces are made of black soap, which is used to cleanse sensitive skin. How poetic and how apt: the very medium of these anxious portraits is a healing substance, yet here, it’s hardened and scarred.

It’s as if all the expectations of strength and resilience (the “you’re so mature” soap that’s supposed to clean away our pain) have solidified, and the only way to breathe is to scratch through that surface.

Looking at Anxious Men, I was reminded that maturity can become a mask for suffering, and that there can be a chorus of silent screams within even the most composed individuals. I wasn’t alone; I was just really good at acting fine.

Sara Ahmed writes, “When you expose a problem, you pose a problem” and I had been unwilling to pose a problem to those around me.

I feared that if I exposed my pain, I’d become an inconvenience, the killjoy in everyone’s happy narrative about the inspiring girl. So I swallowed it until it carved its anxiety on my insides. Suffering is not causing trouble—it’s seeking truth. The real problem was the silence that was killing me.

Escape Velocity

Burnout was not a looming threat; it was my daily reality. I felt bone-tired, like an old woman in a too-young body. Waking up each morning, I often felt a whisper of disappointment that I had woken up, immediately followed by guilt for feeling that way.

How could I, who had been given many opportunities and accolades, dare to feel despair?

This is the twisted logic of the overachiever’s rumination: you think you’re worthless because you’re exhausted from trying to be worthwhile all the time. It’s an escape fantasy, a longing for rest. I started daydreaming about disappearing from the public eye, ditching my responsibilities, and living anonymously somewhere far away.

I fantasized not about self-harm, but about self-erasure: a scenario where I ceased to be “Marley Dias, the girl who’s gets it done.” I craved oblivion like a parched throat craves water. It was frightening to realize how relief—not rage or sadness, but relief—I felt at the thought of not having to perform anymore.

Another of Rashid Johnson’s works entered my life like a lighthouse in a storm: “Untitled Escape Collage.” This series of collages layers lush, tropical images of palm trees and exotic paradises with fragments of Black cultural motifs—African masks, patterned animal skins, and then adorns them with splashes of black wax and strokes of paint.

As critics noted, the work hints at our desire for liberation and escape but also shows the “complicated closeness and distance” of diaspora and identity. It’s escapism with an undercurrent of anxiety—exactly how my fantasies felt.

Johnson said he wanted to explore the agency of Black characters by employing escapism as a strategy, not a negation of reality, but an optimistic reimagining. Looking at Escape Collage, I felt seen in my longing to flee.

The collage is busy, fragmented; it rejects the notion of a coherent and singular self. It told me: you don’t always have to be a cohesive self. You can be a mosaic. You can break and reassemble. Escape might be impossible in full (even Johnson acknowledges “Escape is temporary, at best”), but imagining it can lead us to ask new questions about freedom, as he notes – Where can we go? What’s possible? Those questions became literal: Could I step away from social media? Could I take a semester off? Could I tell my mom I needed help?

In the collage of my life, I had to become the artist. I started to move differently, rather than move on. I scaled back appearances. I said “no” to projects that weren’t nourishing me. I sought out a Black therapist who understood the unique cocktail of pride and pressure that comes with being labeled a “young Black girl genius.”

I leaned on friends who didn’t need me to be an icon, who let me be goofy, messy, even immature. The more I revealed my hidden collage pieces, the more love and support flowed in. People don’t love me for the polished mask; they love me for me. And I am learning to do the same.

Wayward and Willful (Finding Breath)

To situate my struggle in a broader context, I turn to the wisdom of Black feminist thinkers who have long interrogated these themes. Saidiya Hartman writes about wayward girls, young Black women in history who rebelled against the roles forced on them. She describes waywardness as “an improvisation with the terms of social existence…when there is little room to breathe, when you have been sentenced to a life of servitude… It is the untiring practice of trying to live when you were never meant to survive.”

Black girls who speak up, who take up space, who demand more than this world is willing to give—so often, we are not meant to survive. We are supposed to either conform or be crushed.

My “maturity” was a form of conforming—being the good girl who makes everyone comfortable. Something inside me was being crushed. Hartman’s words gave me a framework: my very survival, with joy and whimsy intact, is an act of defiance. My decision to take off the mask, to slow down the race, to breathe, is a wayward practice of carving out life in a world that tries to smother.

Audre Lorde also gave us one of the most radical battle cries for the overwhelmed: “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence; it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.” In a world that praises Black women and girls for being strong mules of the world, caring for ourselves, tenderly, consistently, even selfishly, is revolutionary. I had to learn that rest and joy are my birthrights. That saying “I need help” is brave, not a weakness.

In Lorde’s battle with cancer, she noted that “some of us were never meant to survive.” She urges that survival is a form of resistance for those who live under that shadow. I see that now. Every day I choose to stay, to breathe, to live, even when it feels excruciating, is a day I thumb my nose at a society that would rather use me up and spit me out.

And Christina Sharpe, in her meditation on living in “the weather” of anti-Blackness, describes how Black folks exist in the perpetual storm of history.

“Slavery suffuses our present-day environment in an afterlife called the weather.”

We are always living in the wake of catastrophe.

Perhaps my generation’s accelerated despair—our climate anxiety, our racial battle fatigue, our performance burnout—is a rational response to irrational conditions. Sharpe frames this not to induce hopelessness, but to prompt what she calls wake work—a way of tending to Black life, imagining how to live in the weather.

Part of my wake work is precisely this: writing, reflecting, and creating a THIRD SPACE where I can alchemize pain into prose and anxiety into art. It’s my way of “weathering” the storm, of refusing to drown in it.

As one of Sharpe’s influences, Frantz Fanon, observed, being Black in a white world can feel like “a history…drawing a bit tighter [around your neck], making it hard to breathe.” I name this suffocation now, so I can loosen its grip.

The Market Made Me Do It (Capitalism, Internalized)

I’ve come to understand slowly and painfully that so many of the feelings I thought were mine alone weren’t mine at all. They were symptoms. Of a system. The more I reflect, the more I realize that the pressure to be “mature,” the hunger to prove my worth, the guilt for resting, the desire to disappear—all of it has roots in the same soil: capitalism.

Global, extractive, performance-based capitalism that treats people like products and turns survival into a competition. A capitalism that didn’t just shape the economy—it rewrote the emotional language of life.

I used to think I had impostor syndrome. But I had market syndrome—the feeling that I was only as good as what I could produce, prove, or promote.

I have been a brand since age 10, not always in ways I could control. Every award, every panel, every campaign that called me a “future leader” or a “Black girl magic” came with a subtext: Now don’t mess this up. When you internalize that, you start performing for an imagined audience that never sleeps. I became fluent in the language of impact reports and five-point bios.

It wasn’t until I read Angela Davis’s reflections on how capitalism commodifies care, survival, and identity that I realized how deeply I’d absorbed the logic. She wrote about how the global rise of neoliberalism turns collective pain into personal failure and teaches us to see burnout as a private weakness rather than a political condition.

“We have to talk about liberating minds,” she said, “as well as liberating society.”

I was waiting for a market to save me from exhaustion, but the market was exploiting it. Internalized capitalism told me to monetize my trauma, but not too much. I was to be a symbol of girlhood and grit, but not a mess. I was to sell hope but never name despair. Even the platforms where I told my truth were built on metrics that rewarded me the more consistently I performed pain in digestible, inspiring ways.

In this economy, even healing becomes a brand. And so, of course, I wanted to disappear. Of course, I tried to exit the stage. I wasn’t broken—I was reacting, reasonably, to a world that tries to make all of us consumable.

But I don’t want to be consumed anymore. I want to be cherished.

I want the girls who read this—not just in New Jersey or Geneva, but in St. Louis, Kingston, Brixton, Rio—to know that if you feel crushed by your ambition, it’s not just you. It’s the grind. It’s the system that made your excellence a currency. The global machine rewards our maturity only when it’s productive, profitable, or palatable.

But we can slow it down, step off the wheel, be immature, unsure, and unbranded, and remember that rest is not laziness, failure is not fatal, and our lives are not projects.

As Angela Davis also said,

“You have to act as if it were possible to radically transform the world. And you have to do it all the time.”

This is part of my transformation: writing myself out of the market’s script, and back into my body. Learning that my value isn’t found in my résumé but in my breath.

Even when it’s ragged. Even when it’s new.

Too Young to Quit – and Choosing to Live

I titled this essay “Too Grown to Breathe, Too Young to Quit” because it encapsulates the trap I found myself in. I was too “grown” – responsible, high-achieving, and outwardly composed – to feel like I had permission to falter, or even to fully exhale. And simultaneously, I felt too young to be so tired, too young to be wrestling with thoughts of not wanting to live.

But I write to you now from a different vantage point: not fully healed (what is healing, anyway, but a journey?), but moving differently. I have decided that I am indeed too young to quit—in the sense that I have a lot more living, loving, and silliness to do. I want to see 30, 40, or 90 years old on some porch, cackling at the fact that I almost gave up before things got really good.

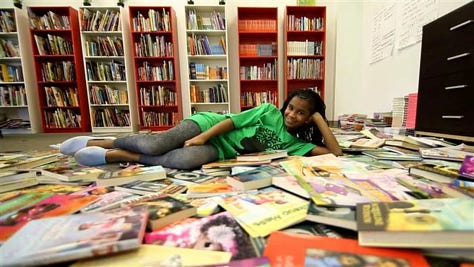

I want to play. I was never “too young” to feel pain, but never too old to reclaim joy. In many ways, I’m rediscovering the immaturity I was forced to shed early on. I’m learning to be authentic from little Marley – the giggly, book-loving, sometimes brattily honest girl I used to be.

If you have ever felt like a prodigy turned hollow, an old soul running on empty, or a success story secretly unraveling, I want to tell you: I see you. You are not a failure for feeling like it’s too much. Sometimes our ideation of escape (even the permanent kind) is our mind’s cry for a life with less pressure and more meaning. It’s the canary in the coal mine of our psyche, signaling that something is deeply wrong in our environment or our approach.

Listen to that signal; it could save your life. It saved mine. I started listening, and what I heard was this: Slow down. Take off the mask. Breathe. The world that praised you for your perfection isn’t the world that will save you. You must save yourself. And you do that by loving yourself in your messiest, most honest form. You do it by asking for help, which, trust me, is there, even in the darkest times.

To be clear, I’m still a work-in-progress. I still have days when the weight of being “wise beyond my years” makes me want to throw it all away and hide under the covers. But now I’ll call a friend and say that. I’ll talk about my sadness and snitch about my stress. I’ll sketch or write or dance to move that energy around.

I’ll remember Rashid Johnson’s anxious faces and know that anxiety is an experience we share, across genders and ages, and that there is strength in naming it. I’ll remember his collages and understand that no matter how shattered I feel, I can arrange those pieces into something new or beautiful. And I’ll remember Audre Lorde and fight for my life by caring for myself fiercely, knowing my life is precious beyond productivity.

I am learning that immaturity can be a form of salvation. The willingness to be a beginner again, to not know, to throw off the heavy cape of “having it all together” is resurrected youth. I’m letting myself be “too young” in the best way: curious, hopeful, a little reckless with laughter. Dancing in the rubble isn't such an evil plan if the world collapses, as it often feels. If we must accelerate, let’s accelerate toward authenticity and community, not just accomplishments.

I want to end this on a note of gratitude and solidarity. Writing this was hard. Sharing it is terrifying. But if even one of you reading this feels a little less alone in your own THIRD SPACE—caught between who you are and who the world expects you to be—then every word was worth it.

We don’t have to quit life to escape the crushing parts; we can quit the myth that we must be perfect to deserve our place here. We can smash out new roads of possibility, create contradictory collisions in our lives that birth new agency, and practice the untiring work of living, even when we were never meant to survive. We will survive.

Thriving can be fugitive, improvised, scrappy—it might not look like a magazine cover. It might look like you, at 2 AM, finally breathing freely after a good cry. It might look like me, taking a semester abroad and not apologizing for it. It might look like all of us, choosing to find each other in these honest moments and saying, “Keep going, I got you.”

Keep going. I got you.

Until next time,

Marley

Want to support my work (and keep me fueled with books, tea, and therapy co-pays)? You can Buy Me A Coffee here.

If you or someone you know is struggling, you are not alone.

988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline (USA): Call or text 988 for free, 24/7 confidential support.

Crisis Text Line: Text HOME to 741741 (USA & Canada) to connect with a crisis counselor anytime.

The Steve Fund: Text STEVE to 741741 to reach a counselor trained to support the mental health of young people of color.

Therapy for Black Girls: (therapyforblackgirls.com) – Find a Black woman therapist and read resources on mental wellness.

BEAM (Black Emotional and Mental Health Collective): (beam.community) – Training, toolkit and support rooted in Black wellness.

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (International): Visit findahelpline.com to find crisis lines in your country.

You matter. The world needs you, not the performing you, but the real you – flaws, fears and all.

This is more common than you or I think. I am sure I am much older than you. I still have the drive to "prove" to my self that I am valueble. I have learned to accept things as they are but I still breath and try hard at everything.