What Juneteenth Looks Like in My Hands

How collage helped me visualize the freedom they tried to erase.

I spread old magazines across my bedroom floor, scissors glinting in the Juneteenth morning light. Headlines, faces, and fragments of history stare up at me.

In these pages are things I was never taught in school, things that lived as whispers in my grandmother’s stories. Freedom didn’t come fully-formed; it arrived in fragments.

To learn about Juneteenth—the day my ancestors finally heard they were free—I had to piece the story together from scraps of family lore and photocopied articles. This is why I make collages: to gather the bits of truth that lay scattered and create a picture of wholeness out of what was broken. Everything I couldn’t say, I cut and pasted.

Cut-Out Girlhood.

I was a quiet Black girl with a cacophony inside. As a child, I clipped photos of my heroes from magazines and taped them in my diary, the way other kids press flowers between pages.

I didn’t have the words yet for the questions in my heart—about race, about being seen, about why our history felt hidden—but I had safety scissors and a stack of old Ebony magazines. In those after school hours, collage became my secret language. I glued Angela Davis’ confident gaze next to the brown-skinned storybook princesses I could find.

I layered sunset colors behind a Black girl’s silhouette and, somehow, that page said what I felt: Here I am. Do you see me?

From the beginning, collage was personal. It was the art of making myself visible. At age 11, I started a campaign to collect 1,000 books about Black girls. Back then I was gathering stories in boxes; now I gather images on paper. In a world that didn’t expect Black girls to be the heroes, I learned to assemble my own archive of heroines. Each snip of the scissors was an act of self-definition. Each arrangement was a prayer that the fragmented pictures could form something like belonging.

The Low End Theory (of Family and Sound).

My father’s vinyl records often kept me company while I collaged. The bass line from A Tribe Called Quest’s album The Low End Theory would thump through the floorboards as I cut and glued. Hip-hop taught me early what collage means: taking disparate samples and making a new whole.

Sampling is just auditory collage—a James Brown horn hit here, a Nina Simone vocal there, spun into something fresh and defiant. Growing up, I realized Black culture has always been about remixing and redefining. Our music, our language, our style: a gorgeous patchwork quilt. When the present offered silence or erasure, we sampled the past to make our voices heard.

Sitting on the floor, I’d hum along and wonder: did my great-great-grandmother have anything that gave her this feeling? Maybe not music on vinyl, but perhaps a quilt frame, a church hum, a shoebox of letters.

Collage feels like kinship with those earlier creations. Black women have long made art from what was available—piecing together quilts from rags, braiding hair into intricate styles, mixing herbs into remedies. I imagine some ancestor of mine, forbidden from learning to read or write, quietly making scrapbooks or sewing story-quilts to preserve what she could of herself. Art as survival, art as witness. Art as a ritual of becoming whole.

A Lineage of Fragments.

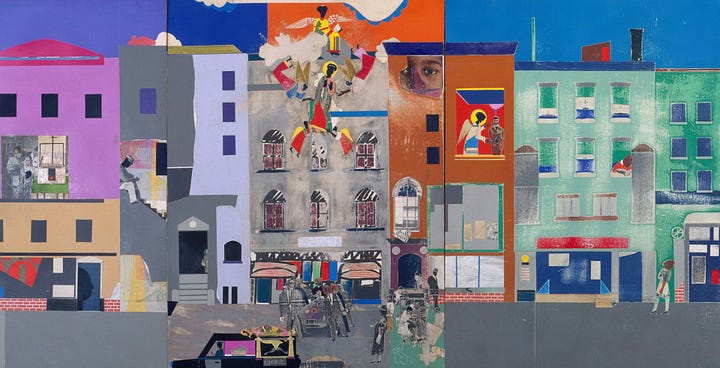

When I first saw Romare Bearden’s collages, it was like meeting a grandfather I never knew I had. Bearden was a towering artist of the 20th century who turned bits of paper into bold truths. During the Civil Rights era, he joined other Black artists in a collective called Spiral to ask: What is our role in the fight for equality?

Bearden’s answer was to cut and paste. He began experimenting with collage as a way to piece together fragments of Black life, history, and memory. In 1964, he created a series called “Projections” that enlarged his small collages into big statements on Black experience.

He understood that the struggle wasn’t only in marches or sit-ins. It was also fought in images and representation—on museum walls and magazine pages. His collages reclaimed Black identity, challenging stereotypes and offering richly textured narratives of everyday life

When I glue an image of a little Black girl next to one of a jazz musician and an old Frederick Douglass quote, I feel Bearden’s legacy guiding my hands. He showed that a torn photograph could become a political shout, a church choir, a neighborhood, a memory you can hold.

Through collage, Bearden insisted that all the disjointed pieces of our history belonged in the story, that Black people could assemble our own mirrors and see ourselves whole.

The Spirit of Lorna Simpson.

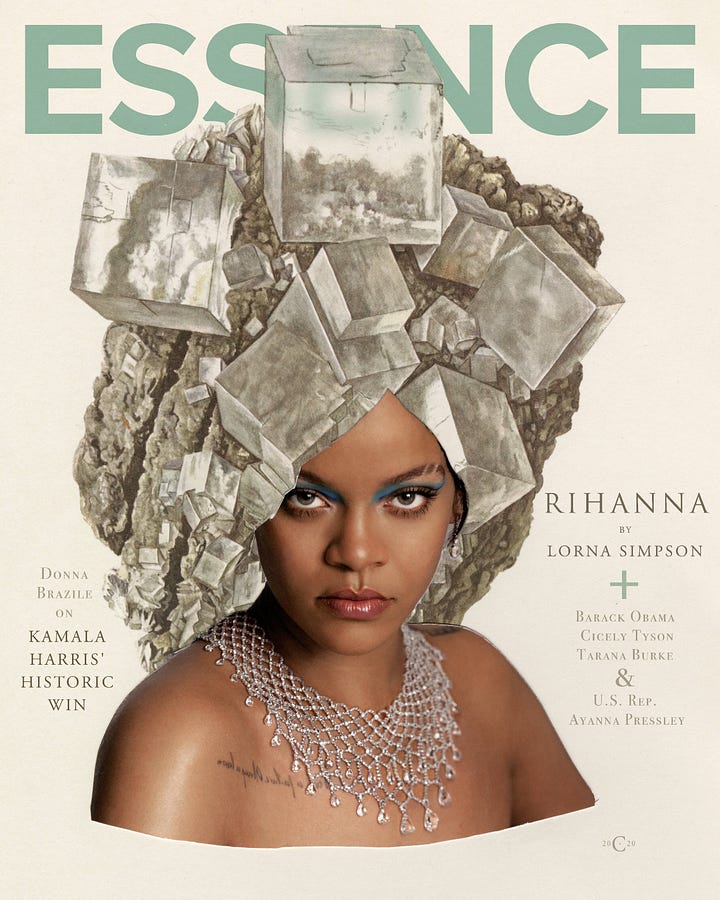

If Bearden is a grandfather spirit in my art, Lorna Simpson is like an auntie teaching me new tricks. Simpson is a contemporary artist who, decades later, picked up the scissors and pushed collage in a direction that speaks so deeply to me as a Black woman. She took vintage images of Black people—especially Black women—from old Jet and Ebony magazines and remixed them into something surreal and poetic.

Those magazines were where our parents and grandparents saw themselves honored and demeaned all at once: glossy pages celebrating Black beauty on one page, a reminder of America’s pains on the next.

Simpson cuts out those models in their Sunday best and sets them in new constellations: a woman’s afro becomes a galaxy of stars, another sister’s body merges with a bird or a blooming crystal. The added pieces bridge time and conjure new narratives, speaking to the imagined lives and complex interiority of her subjects.

In Simpson’s collages, fragments of the past meet fantastical futures. They ask, Who was this woman, and who could she have been?

One of Simpson’s insights that stays with me is about fragmentation. She notes,

“the notion of fragmentation, especially of the body, is prevalent in our culture… We’re fragmented not only in terms of how society regulates our bodies but in the way we think about ourselves”.

I feel that in my bones. Black girlhood can make you feel cut into pieces—one part of you expected to be strong, another hyper-visible, another invisible, all at the same time. Collage became the way I reclaimed those pieces.

Every time I take a beautiful Black face from a 1960s magazine and place it in a new context, I’m performing a quiet act of healing. I am saying: You are not an object or an afterthought; you are the center of the story.

By blending figuration and abstraction, Simpson developed a language to explore identity and race that I now borrow like a beloved book from the library. In my collages I, too, mix the real and the dreamlike—because our lives are both. We live in a world that tries to fragment us, yet inside we carry whole universes of imagination.

Juneteenth: Fractured Freedom Day.

Today is Juneteenth, a day of jubilee—and of solemn remembrance. On June 19, 1865, people enslaved in Galveston, Texas finally learned they were free, two and a half years after the Emancipation Proclamation was signed. Can you imagine that delay? Freedom was granted on paper, but it took its time reaching the people whose lives hung in the balance. Deliberate delay, willful silence—another form of fragmentation, slicing some of us away from the promise of liberty.

For those Texans, emancipation came like a letter lost in the mail: a tattered envelope arriving ages late, carrying life-changing news and the bitter knowledge of its lateness.

Juneteenth has always been a celebration of freedom mixed with anger and resolve. Juneteenth celebrations were as much about the unfinished work of freedom as about the accomplished fact of slavery’s end.

Emancipation wasn’t a clean, complete act—it was, and is, an ongoing process. Freedom for Black folks has always been a collage, assembled bit by bit.

One law ends slavery, another ushered in Jim Crow. One victory grants the vote, another setback snatches it away. We claim a fragment of joy here, a shred of justice there, and we keep piecing them together. Unfinished freedom is our inheritance; we must keep the scissors at the ready to cut through the next barrier, to paste a new vision over the old lies.

I think of the women of Galveston, who, as soon as they heard the news, got busy making Juneteenth a day of community. By 1872 they pooled $800 to buy land for Emancipation Park so there’d be a place to celebrate being free.

They understood that freedom needs space to flourish. They held parades where little Black children marched in their best, claiming the streets that once they could only cross with permission. But they also spoke hard truths at those gatherings: freedom had come late and on cruel terms, with no 40 acres and a mule, no reparations.

Those early Juneteenth commemorations were part cookout, part political rally. Celebration and protest, hand in hand – a collage of emotions in its own right.

Juneteenth reminds me that liberation is messy. It doesn’t arrive all at once like a sunrise; it’s more like a mosaic that we keep adding tiles to. When I cut out pictures of shackled wrists breaking free or young protestors with signs, I place them next to golden shards of light or kente cloth patterns.

It’s my way of visualizing this truth: freedom is made, not given. It’s assembled from the brave acts of everyday people, from generations of resilience.

Collage is the perfect metaphor here. To collage is to believe that what is torn can be rebuilt, that from the shredded remnants we can make something new and whole. In the scattered remains of slavery’s aftermath, Black folks created new identities, families, traditions. We took scraps and made soul food, we took sorrow and made spirituals, we took junkyard parts and made jazz. We are collage artists by necessity and by genius.

Final Girls and New Legends.

There’s a term in horror movies—“the final girl”—for the one who survives the nightmare. The one who emerges bloodied but breathing, scarred but unbroken. Black history is full of final girls and final boys.

We’re descendants of people who lived through the unspeakable and kept living, who held memory in their bones and passed it on like gospel. I often feel that every Black child in America is born with some version of that instinct: a quiet knowing that survival is not luck, it’s legacy. That we are here because someone before us refused to disappear.

My collages often honor those survivors—not as symbols, but as breathing proof that we’ve always outlived what tried to end us.

But survival doesn’t look the same for everyone. Some of us are fighting for breath not just because of our skin, but because of our gender, our orientation, our refusal to shrink. "Final Girls" wasn’t a Juneteenth piece. It was a mirror I built when I needed to see myself clearly—Black, queer, soft, and still standing.

It’s layered with imagery of Black women warriors, protest slogans like “Resist Colonial Power By Any Means Necessary,” and the words “Final Girls” emblazoned like a dare.

I made it for the nights I felt too complicated to exist in one piece. For the friends who taught me how to hold hands in public and laugh with our heads thrown back like we weren’t afraid. For the girls who learned how to fight and kiss and grieve at the same time.

This collage is jagged on purpose. It wasn’t meant to be pretty—it was meant to be true. There are no straight lines in queer Black survival. There are only sharp edges and soft spots.

Trauma and tenderness. Beauty and backlash. The final girls I know didn’t get a happy ending—we built our own sanctuary from scraps. The finished collage looks chaotic up close—images crowding, headlines clashing—but from a distance it tells a story. Not of tragedy, but of reclamation.

In the collage of Black freedom, we must make room for the full spectrum of who we are. We cannot talk about liberation and leave out those of us who were never expected to survive. Those who were never centered in the freedom narratives. The final girls win not because they’re unscathed, but because they refused to disappear. Because they kept dancing, kept loving, kept cutting out a place to belong.

That’s what this collage taught me: that sometimes freedom is found not in celebration, but in visibility. That queer Black life isn’t just resistance—it’s art.

It’s defiance. It’s joy pressed onto the page with glue-sticky fingers. And it belongs in the story. Always.

Cutwork (for Juneteenth, for the ones still cutting)

I wasn’t born whole— I was assembled. Braided together from women who hummed warnings into skillet smoke, who tucked freedom papers beneath floorboards, who knew silence could be a sermon if you held your breath long enough. I didn’t inherit legacy, I inherited scraps: a ribbon from my mother’s hair, my father’s half-finished prayers, newsprint headlines that never mentioned us unless we were stolen or magic. So I cut. Not for pretty. For proof. I slice history down the dotted line, steal back the pieces they cropped out— our hips, our joy, our genius, our goddamn names. Collage is not craft. It’s conjuring. I call my ancestors with glue-sticky hands, set the table with torn saints, serve memory as meat. Romare gave me the scissors. Lorna gave me the spell. Juneteenth gave me the reason. They freed the body. I’m freeing the image. The story. The space. You want clean lines. I bring jagged truth. You want a portrait. I bring a mirror still foggy with grief, still gorgeous with fight. I don’t owe coherence. I owe honesty. And this— this bleeding page of clippings, this quilt of riot and rhythm— this is my emancipation.

Art as Ritual, Collage as Prayer.

I often make collages in a state that feels like prayer or trance. Late at night, when the city quiets, I’ll light a candle on my desk. A scent of lavender, a little music low in the background (maybe Solange or Billie Holiday).

I sit with my scissors and images, not rushing, letting intuition guide me. It feels like how my aunties must feel shelling peas on the porch or braiding a cousin’s hair for hours.

Collage is my ritual of reflection. As I cut, I might silently ask a question: What needs to be healed? As I paste, I might set an intention: Let this piece bring someone hope.

It’s creative free-form; there’s no right or wrong. I tear a page, reposition a picture, add a swath of color — improvising until it feels right.

It’s unfiltered daydreaming poured onto paper. In a world that demands perfection and productivity, collage is unconditional play, a return to the inner child who just wants to create without fear. In those moments, art becomes a healing ceremony.

Group of women in decorated carriage. Photograph by George McCuistion of Juneteenth celebrations in in Corpus Christi, Texas, 1913.

I think about how, historically, the act of making art was sometimes the only space of freedom our ancestors had. Singing in the fields, carving ornate walking sticks, painting murals in segregated schools, or collaging images in a journal—each was a small liberated zone, a THIRD SPACE beyond oppression, where the spirit could breathe.

That’s why I named my newsletter Third Space: it’s the idea of a safe space we carve out, at the intersection of who we are and who we’re becoming. Collage is one of my third spaces.

When I engage in this ritual, I commune with those who came before. The lines between generations blur: I imagine an ancestor’s hand on mine as I press the glue. I cut and I pray. I paste and I sing. It is meditation and revolution all at once.

Pasting a New World Together.

The practice of collage has taught me that brokenness is not the end of the story. In fact, broken pieces can be the beginning of art.

Juneteenth, too, teaches that a broken promise of freedom can become a new fight, a new feast day, a new fire in our hearts.

Black freedom is a story still being written, a collage still in progress. We add to it with each generation.

My collage work is just one tiny fragment of that greater picture—a continuing lineage from Bearden’s bold shapes to Simpson’s ethereal cut-outs to the scrapbooks of ancestors whose names I’ll never know but whose spirit I carry.

On this Juneteenth, I invite everyone to think of the pieces of freedom we each hold. Maybe it’s a story from your grandmother, maybe a song, maybe a talent you use to uplift others.

Gather those scraps. Make your collage. As we cut and paste, we remember and we imagine. We honor what was, and we shape what could be.

And one more thing—

If you loved this piece, you’ll want to check out Black Girls on Substack, a new space by and for Black girl writers, artists, and dreamers 25 and under. I’ve founded it alongside

.The plan is simple: a newsletter where we share our work, shout each other out, and remind each other that our voices deserve spotlight.

If you know a young Black girl who writes—poetry, prose, essays, anything—please pass it on.

And if that girl is you? Subscribe, submit, show up. We’re building something special, and there’s room at the table.

The table is scattered with clippings of the past and visions of tomorrow, but in our hands, they can become something beautiful and true. Together, we are cutting out what no longer serves us and pasting a world where all of us are free.

In this bold, collective collage called liberation, every piece matters—every voice, every story, every Juneteenth jubilee and protest and poem. Everything we couldn’t say, we can express now, in living color.

And if the picture still isn’t complete, that’s okay. We’re still adding to it. We’re still here, scissors in one hand and hope in the other, creating freedom one fragment at a time.

Happy Juneteenth. Let’s keep making something out of nothing, until our mosaic is whole.

Until next time,

Marley

If this piece stirred something in you—made you feel seen, helped you remember, or gave you new language for your own scraps of memory—subscribe to Third Space to get future essays, rituals, and reflections like this straight to your inbox.

If you want to support my work (and help fund the glue sticks and late-night writing sessions that keep me going), you can buy me a coffee.

Every bit of support makes it possible for me to keep cutting, pasting, and building toward something freer—on the page and beyond.

Thank you for being here. Always.

I love this, glad the collective Unconscious brought me to this app 🕉️🌬️💜

I've just recently started collaging too! It feels so right and just flows right out of me. Such a beautiful ritual and gift to the ancestors 🙏🏽